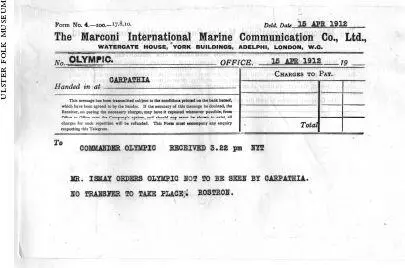

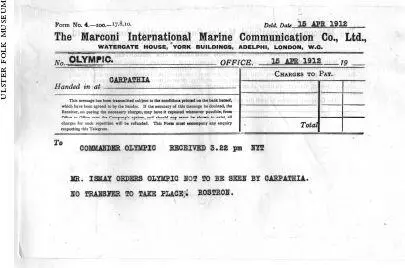

As Ismay lay on his bed in the Carpathia on the morning of Monday 15 April, contemplating as best he could the events of the last twelve hours, the Olympic was heading towards them. Built alongside one another in the Harland & Wolff dockyards, the Olympic was the Titanic’s twin. ‘Everything was taken to be doubled,’ the chief designer said of their construction. ‘Anything which was taken up for one applied to the second ship the same.’ 23The interiors of the two liners were mirror images of one another; passengers on the Titanic were provided with maps of her layout which belonged to the Olympic. Captain Haddock of the Olympic now telegraphed the Carpathia: perhaps, he suggested, the Olympic might relieve Captain Rostron of his White Star passengers? Rostron’s response to Haddock’s request was cautious: ‘Do you think it advisable the Titanic’s passengers see Olympic? Personally, I say not.’ After a brief exchange with Ismay, he then sent another, more urgent, message to Haddock:

It was ‘very undesirable’ Ismay later explained to the inquiry, ‘that the unfortunate passengers from the Titanic should see her sister ship so soon afterwards’.

The liner on which Captain Edward John Smith had died was an age away from the rigged ships in which, aged sixteen, he began his life at sea. A working-class boy from Stoke-on-Trent, Smith’s older stepbrother, Joseph, was a sea captain who had been captured by pirates; the young Edward longed for similar adventures. To prevent the lad from running away to Liverpool and signing up on the first available barque, Joseph had taken Edward with him on his next voyage. But after years of transporting ossified bird dung and sleeping eight to a cabin with his trunk lashed to the floor by iron rings, Smith fixed his eye on the glamour of the White Star Line. No more oilskins, weevil-infested biscuits and cussing sea dogs; here was romance of a higher order. He was thirty when he joined White Star in 1880, and seven years later he attained the rank of Captain. His first command, the Republic, was a hybrid of steam and sail; one lonely smokestack nestled inside a forest of masts. In 1888, Captain Smith was transferred to the Republic’s twin sister, the Baltic: the White Star Line always built ships in pairs. ‘My love of the ocean that took me to sea as a boy has never left me,’ he later said. ‘In a way, a certain amount of wonder never leaves me… There is wild grandeur too, that appeals to me in the sea.’ 24

By 1892, Smith was the most highly respected skipper in the British merchant service and he was rewarded with the honour of taking each new White Star liner on her maiden voyage. Known as the ‘millionaire’s Captain’, he was now a celebrity seaman — travelling under Captain E. J. Smith was as thrilling as being on the Titanic itself — and his salary, twice what Rostron was earning with the Cunard Line, reflected his status. Smith was described by Lightoller as ‘a great favourite’ of any crew, a man everyone wanted to work under: ‘Tall, whiskered and broad, at first sight you would think to yourself, “here’s a typical Western Ocean Captain. Bluff, hearty and I’ll bet he’s got a voice like a foghorn”. As a matter of fact, he had a pleasant, quiet voice and invariable smile. A voice he hardly raised above a conversational tone — not to say couldn’t, in fact.’ 25J. E. Hodder Williams, of the publishers Hodder and Stoughton, who crossed the Atlantic with Captain Smith on many occasions, thought him ‘the perfect sea captain’. He ‘had an infinite respect for the sea. Absolutely fearless, he had no illusions as to man’s power in the face of the infinite.’ The American writer Kate Douglas-Wiggin gave an account in her autobiography of how she crossed the Atlantic with Smith over twenty times.

There were no electric lights then, nor ‘Georgian’ or ‘Louis XIV’ suites, no gymnasiums or Turkish baths, no gorgeous dining salons and meals at all hours, but there were, perhaps, a few minor compensations, and I can remember certain voyages when great inventors and scientists, earls and countesses, authors and musicians and statesmen made a ‘Captain’s table’ as notable and distinguished as that of any London or New York dinner. At such times Captain Smith was an admirable host; modest, dignified, appreciative; his own contributions to the conversation showing not only the quality of his information but the high quality of his mind.

Captain Smith offered an uneventful but glamorous voyage; it is part of the strangeness of the sea that a captain who on shore lives a quiet suburban life, becomes an object of fascination when on board his own ship.

On the Titanic, the Marconi operators received or intercepted eighteen separate ice warnings; some of these Captain Smith saw, one of them he passed on to Ismay, one he showed to Lightoller, while several never made their way onto the bridge. On the evening of 14 April, while the Captain was at a dinner party given in his honour by a party of American millionaires, the iceberg, whose position he was aware of, was only fifty miles ahead. Captain Smith was losing his fear of the sea: it was the grandeur of the ships rather than that of the water which now gave him cause for wonder. ‘When I observe from the bridge’, he told a reporter, ‘a vessel plunging up and down in the trough of the seas, fighting her way through and over great waves, tumbling, and yet keeping on her keel, and going on and on — I wonder how she does it, how she can keep afloat in such seas, and how she can go on and on safely to port.’ 26When he brought the Adriatic to New York on her maiden voyage in 1907, Smith told journalists that ‘shipbuilding is such a perfect art nowadays that absolute disaster involving passengers is inconceivable. Whatever happens, there will be time enough before the vessel sinks to save the life of every person on board. I will go a bit further. I will say that I cannot imagine any condition that would cause the vessel to founder. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.’

The most enigmatic member of his crew, it is impossible to account for the final moments of Captain Smith. After informing Ismay that the ship was sinking, he seemed to melt away. Some said that he took up his megaphone and ordered the international population of men and women to ‘Be British, my lads’, while other witnesses have him variously firing a gun into a crowd, turning the gun on himself, and jumping overboard with a baby swaddled in his arms. In another version, he is last seen in the water swimming alongside a lifeboat; when an oar is held out to him, he says, ‘Goodbye boys, I’m going to follow the ship.’ There are the inevitable rumours of his survival, including a sighting of him alive and well in Baltimore, but it seems most likely that Captain Smith died on the bridge, where he was standing alone. As he was not wearing a lifejacket, he was at least spared the slow death from hypothermia suffered by most of the others. Mrs Thayer said she saw the Captain after midnight, on the port side of the bridge, and Lightoller, who was working on the port side all night, says that Smith ordered him to start loading women and children into lifeboats from the promenade deck, one level below the boat deck, forgetting that, unlike the Olympic, the promenade deck on the Titanic was fully glazed with what were known as ‘Ismay’ screens, a sheltering wall which Ismay suggested at planning stage would protect the promenading passengers from sea-spray. The Ismay screens on the Titanic were the only visible difference between the two sisters. The passengers, once they had been herded down to the lower deck, had to be pushed headfirst though the opened windows and into the boats. Captain Smith’s confusion about which ship he was on reveals something of his frame of mind.

Читать дальше