Lawrence Beesley, who based his experience of the Titanic on adventure stories (and became father-in-law to the novelist Dodie Smith, who wrote One Hundred and One Dalmatians) was later turned into a literary figure himself. Julian Barnes describes in A History of the World in ioV2 Chapters how, when Pinewood Studios filmed A Night to Remember on a pond in Elstree Studios, Beesley asked to be an extra in the scene where the ship goes down. Not having the necessary actor’s union card, permission was denied. But so determined was he to repeat the pivotal experience of his lifetime that, dressed as an Edwardian, he slipped unnoticed onto the set. ‘Right at the last minute,’ writes Barnes, ‘as the cameras were due to roll, the director spotted that Beesley had managed to insinuate himself to the ship’s rail; picking up his megaphone, he instructed the amateur imposter kindly to disembark. And so, for the second time in his life, Lawrence Beesley found himself leaving the Titanic just before it went down.’

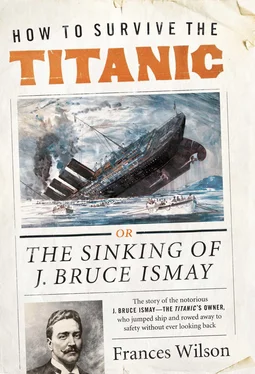

Contemplation and reflection played no part in Ismay’s daily routine. Described by a friend as ‘austere, uncompromising and intolerant to the weaknesses of human nature’, Ismay resisted the effects of even minor daily disorder and shielded himself from what events he could not control. The loss he now suffered was beyond anything that could be measured. Incapable of articulating, or even comprehending, his response to the wreck, he said nothing on board the Carpathia. He detached himself from the experience of Sunday night, he froze himself into the present tense. The disaster, Ismay decided, had nothing to do with him; it happened around him, not to him and certainly not because of him. ‘Has it occurred to you,’ he was asked at the British inquiry, ‘that, except perhaps apart from the Captain, you, as the responsible managing director, deciding the number of boats, owed your life to every other person on that ship?’

‘It has not,’ Ismay replied, in all honesty. And yet the same friend who had described Ismay’s intolerance of human weakness also noted that ‘no one could be kinder or more sympathetic or enter more fully into the troubles of others… Had I to sum up his character in one word — it would be that of Integrity.’ 18

The only crew member from the Titanic to see Ismay on the Carpathia was Second Officer Charles Lightoller, the most senior of the four surviving officers. Lightoller, another Christian Scientist, described in an article for the Christian Science Journal the following October how ‘all fear left me and I… realised the truth of being’.

Swept off the ship, Lightoller spent the night, along with twenty-eight other frozen men, straddling a capsized lifeboat. Aged thirty-eight in 1912, he had been at sea since he was thirteen and experienced two shipwrecks before he was twenty-one. An employee of the White Star Line for fourteen years, before joining the crew of the Titanic he had been an officer on the Oceanic. In a longer account of the disaster, written twenty-three years later, Lightoller describes how, as the ship was sinking, he was standing ‘partly’ in a lifeboat helping to load the women and children when Captain Smith suggested that, as there were no other seamen available to man the boat, Lightoller should ‘go with her’. ‘Praises be’, Lightoller remembers in horror, ‘I had just sufficient sense to say “Not damn likely” and jump back on board.’ Ismay’s opposite, Lightoller is distinguished for having jumped off a lifeboat and onto a sinking ship. He acted, he said, on ‘pure impulse… an impulse for which I was to thank my lucky stars a thousand times over in the days to come’. 19

Lightoller later explained to those who were bewildered by Ismay’s behaviour on the Carpathia, that the chairman of the White Star Line was ‘obsessed’ by guilt; as he lay on his bed, a wretched figure, he ‘kept repeating that he ought to have gone down with the ship, because he found that women had gone down’. 20But according to Ismay’s account, he did not know that women had gone down on the Titanic. Asked at the US inquiry what proportion of women and children were saved, he replied, I have no idea, I have not asked.

On the Thursday, 18 April, Dr McGhee suggested that Jack Thayer visit Ismay before the Carpathia docked in New York, to ‘help relieve the terribly nervous condition he was in’. The seventeen-year-old, who had jumped from the ship and been saved by the same capsized lifeboat as Lightoller, went down to the doctor’s cabin immediately and later described how, ‘as there was no answer to my knock, I went right in. [Ismay] was seated, in his pyjamas, on his bunk, staring straight ahead, shaking all over like a leaf. My entrance apparently did not dawn on his consciousness. Even when I spoke to him and tried to engage him in conversation, telling him he had a perfect right to take the last boat, he paid absolutely no attention and continued to look ahead with his fixed stare. I am almost certain that on the Titanic his hair had been black with slight tinges of grey, but now his hair was virtually snow white.’ 21

Ismay may have been less concerned that he had failed his passengers than that he had failed his father, a legendary man in the shipping world. But what dominated his thoughts was the idea that his ship had failed him. Whatever the size and splendour of your ark, he now realised, the sea is the irreconcilable enemy of ships and men and optimism. This is what Joseph Conrad, who spent half his life at sea, understood: ‘When your ship fails you,’ he wrote in Lord Jim, ‘your whole world seems to fail you.’ The Titanic had been Ismay’s pride, his passion, his palace. She was indestructible, the culmination of his father’s ambition. She had promised to garland the family name in laurels, to bestow on Ismay honour, glory, and unchallenged dominion of the waves. ‘The love that is given to ships,’ says Conrad in The Mirror of the Sea, ‘is profoundly different from the love men feel for every other work of their hands.’ It is ‘untainted by the pride of possession’. Conrad was describing the love that is given to ships by the crew rather than by the owner. In his memoirs, Lightoller also talked about ‘the loyalty between a ship and her crew’: ‘It is not always a feeling of affection either. A man can hate his ship worse than he can hate a human being… Likewise a ship can hate her men.’ 22To the crew, the owner was as distinct from a seaman as a duck from a dolphin; shipowners were not romantic wanderers, they were men of order and control, fastidious pen-pushers ill-suited to the unruliness of the oceans. Men like Lightoller assumed that the owner would see his ship as no more than a description of profit and loss. But Ismay was not typical; he loved the Titanic like ‘a living thing’, as his wife put it. Perhaps, he later wrote to Marian Thayer, he had loved this ship ‘too much’, had been ‘too proud’ and such was his punishment. Ismay had grown in stature with his ships. Three years earlier Winston Churchill announced in The Times the arrival of ‘a new time. Let us realise it. And with that new time strange methods, huge forces, larger combinations — a Titanic world — have sprung up around us.’ This was Ismay’s world. And now, like a Titan, he had angered the gods.

‘All fates’, wrote Evelyn Waugh, ‘are “worse than death”’, and for Ismay the awareness of lost honour was the worst fate of all. There was a difference, he now understood, between surviving and being alive. Lawrence Beesley felt the euphoria of having narrowly escaped death and Lightoller considered his continued life a miracle; but Ismay’s attitude suggests that he took for granted that he was living while others were not. He was on the Carpathia, he accepted, not because an impulse had caused him to jump, but because his drive to survive had been greater than that of many other men on the Titanic. Ismay was profoundly shocked by the mortality of his ship, but unsurprised at his own durability. Comments he later made in correspondence suggest that he was wearied by his continued consciousness as though it were his curse to escape unscathed from every cut-throat situation, his burden to vary from the happy race of men who die when their allotted time is up.

Читать дальше