Original battle flag from the Battle of Cowpens.

Library of Congress

I like to think of my ancestor Major Houston Sr. standing beside Dan Morgan as the redcoats surrendered. It’s recorded that the Americans graciously treated the defeated British officers to a delicious feast to show their honor. If Major Houston was anything like me, he introduced those tea drinkers to venison steaks and American whiskey. Now, that’s honorable.

Remember Tim Murphy, the sniper who killed General Fraser at Saratoga with a shot from his long rifle?

He was reported to be in the crowd of American soldiers who witnessed the surrender ceremony at Yorktown, when eight thousand British troops stacked their guns and a military band played “The World Turned Upside Down.”

I bet he had a fat grin on his face.

When I was growing up, I heard a lot of different stories about Sam Houston Junior. Some of them weren’t too good—you see, he earned a reputation among some folks as a general who ran away from the action during the Texas Revolution.

My ancestor, a coward?

Damn.

But if you check deeper into the story, you’ll see that Sam—founding father of Texas—wasn’t a coward at all, far from it. He was a hell of a crafty tactician and a master strategist. Though sometimes, as Dan Morgan proved at the Battle of Cowpens, running away from your enemy can turn out to be a good way to smash him right in the jaw.

Samuel Houston Sr. died when his son was fourteen years old. But I think it’s entirely possible that father and son might have talked about what happened at Cowpens, and maybe—just maybe—that served as inspiration for what became Sam Houston’s biggest moment on the battlefield in the spring of 1836.

In the decades after the Revolution, Americans kept pushing west—and took their long rifles with them every step of the way. They proved themselves on the frontier, and even did service in the War of 1812—not a particularly fun war for the U.S., though it at least showed Britain we wouldn’t let them push us around without fighting back. Then between October 1835 and April 1836, long rifles and a host of other firearms starred in Texas settlers’ bid to shake free from Mexico. In fact, the Texas Revolution was like a big gun show, showcasing the grab-bag assortment of weapons available on the open market at the time. It also offered a last snapshot of the old firearms designs that were soon to give way to new technologies. There is no good inventory of the guns used at these battles, but experts make educated guesses.

When Mexican dictator and president-general Antonio López de Santa Anna and his troops marched up to the Alamo in late February 1836 and began their epic thirteen-day siege, they outnumbered the fewer than two hundred rebellious Texas volunteers inside the fort by 10 to 1. Here and at the later Battle of San Jacinto, both sides would have been armed with European-patterned, muzzle-loading, single-shot, flintlock muskets like the English Brown Bess and some French models, too, plus Spanish-style escopeta short muskets and Spanish pistolas that would have featured the classic Miquelet lock.

The Texans would have had American long rifles, but also “blunderbuss” short-range muskets, carbines (a shorter version of the musket or rifle, often preferred by cavalry), bird guns, and some pistols here and there. The Texans may even have had a few guns featuring the new “caplock” or percussion-cap firing mechanism, which was a big improvement on the flintlock because it replaced the troublesome flash pan and flint with a sturdy, waterproof copper cap that triggered a spark when it was struck. Toss in some Bowie knives, tomahawks, and Belduques (a long fighting knife similar to the Bowie), and you’ve got yourself a gang that can really do some damage.

During the Battle of the Alamo, one legendary American long-rifleman was spotted on the wall by Captain Rafael Soldana of the Mexican Army. The “tall man with flowing hair” on the wall wore “a buckskin suit with a cap all of a pattern entirely different from those worn by his comrades. This man would rest his long gun and fire, and we all learned to keep a good distance when he was seen to make ready to shoot. He rarely missed his mark, and when he fired, he always rose to his feet and calmly reloaded his gun, seemingly indifferent to the shots fired at him by our men. He had a strong, resonant voice and often railed at us.”

Soldana later learned the man was known as “Kwockey”—the national celebrity frontiersman and former congressman Davy Crockett.

After almost two weeks of siege, Mexicans punched through the Alamo’s flimsy defenses and killed or massacred all but two of the Texan defenders of the Alamo, including Crockett. A month later, when General Santa Anna ordered the cold-blooded bayonet-and-bullet massacre of 353 more Texan prisoners near Goliad on Palm Sunday, March 27, terrified Texas civilians started fleeing eastward.

The panicked exodus was called the Runaway Scrape, and Texas General Sam Houston assumed the role of Skedaddler-in-Chief. Day after day, Sam led his troops eastward, away from Santa Anna, moving as fast as he could in the direction of Louisiana. Texas politicians were appalled, as were some of Sam’s own troops. They publicly wondered if he was a coward.

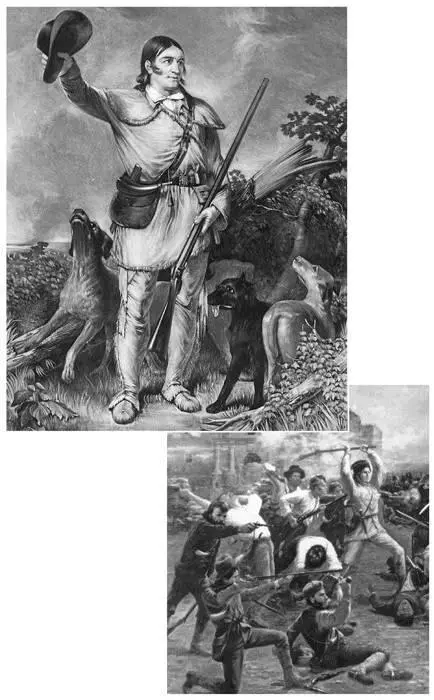

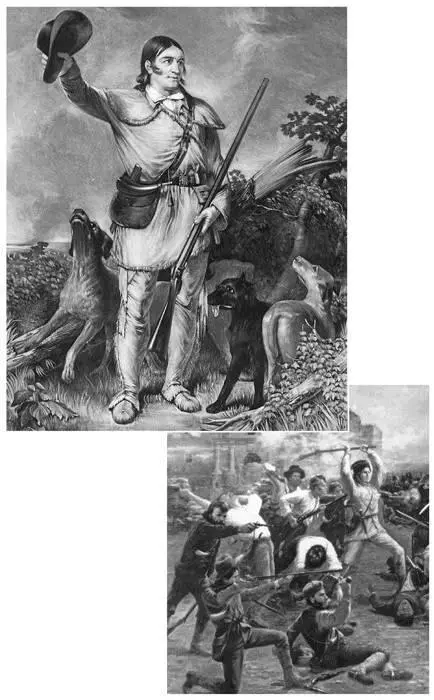

“The King of the Wild Frontier”: Born in Tennessee, Davy Crockett died, long rifle in hand, defending the Alamo in 1836.

Library of Congress

But Houston was just biding his time, looking for an opening to turn around and strike. The deeper Santa Anna marched into Texas, the more worn out his troops and equipment got. Camped near the meeting of the San Jacinto River and the Buffalo Bayou, Santa Anna decided it was time for a siesta on the afternoon of April 21, 1836. He forgot to post sentries. His men lay snoozing as a burly, mangy-looking Sam Houston and his more than eight hundred Texans and their allies snuck up through the cover of a forested hill, led by a contingent of uniformed Kentucky riflemen. “Now hold your fire, men,” Houston cautioned, “until you get the order!”

It was time for payback, Texas-style.

Screaming “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” the Texans overwhelmed the Mexicans in a mere eighteen minutes, enough time for Sam Houston to lose two horses—both shot out from under him—and sustain a bad gunshot wound to the ankle.

The Texans were in no mood for mercy and unleashed a full-scale slaughter. No one was spared, not even the wounded or soldiers trying to surrender. “Take prisoners like the Meskins do!” shouted one Texan, and scores of Mexicans were shot to pieces after surrendering, or hunted down in the river and clubbed to death while pleading “Me no Alamo!” or “Me no Goliad!” A horrified Sam Houston tried to stop the massacre, shouting “Parade! Parade!” in a vain attempt to call his men back to form a dress formation and leave off killing. By the time the butchery stopped, a total of 630 Mexicans died that day, versus nine Texans.

The people of Texas were jubilant, grasping that independence was theirs. A messenger raced into one refugee camp on the Sabine River waving his hat and shouting, “San Jacinto! San Jacinto! The Mexicans are whipped and Santa Anna a prisoner!” A lady named Kate Scurry Terrell witnessed the reaction and wrote: “The scene that followed beggars description. People embraced, laughed and wept and prayed, all in one breath. As the moon rose over the vast flower-decked prairie, the soft southern wind carried peace to tired hearts and grateful slumber.”

Читать дальше