But like presidents before and after him, Lincoln would soon find that executive power was often more theory than promise. Even though his War Department placed initial orders of 25,000 of the Marsh guns and 10,000 seven-shot Spencer Repeaters before the end of 1861, they didn’t reach Union troops. Or anyone else.

If I were writing this up as fiction, I might spin a yarn about a daring Confederate attack against the factory, complete with 1860s-style special ops work, fine explosions, and general pandemonium. But the Rebs had nothing to do with it.

No, a Yankee was responsible for sabotaging Lincoln’s plans to get modern technology into the hands of his men. And not only was he on the Union’s side, he was one of its highest ranking officers.

Head shed’ll get you every time.

James Ripley was an ultrapowerful bureaucratic monster, a cantankerous, backward-looking, sixty-seven-year-old Northern Army general. He was the chief of Army procurement, and he was a wizard of red tape, delay, and obfuscation. Truth be told, he was also a master at supply logistics and standardizing artillery ammunition, but he was an idiot when it came to guns. He hated breech-loading weapons, even the superb Sharps rifle, considering them “newfangled gimcracks.” And he absolutely detested repeating rifles like the Spencer Repeater. By his convoluted logic, soldiers would only waste ammunition with a multi-shot gun. He wasn’t crazy about the prices, either: he could buy good muskets for $18 each from multiple vendors, but a Spencer Repeater was $40.

Through the end of 1861 and much of 1862, General Ripley conducted a one-man mutiny of disobedience and delay against President Lincoln, General-in-Chief George McClellan, and many other officers and regular troops who were begging for breechloaders and repeaters. He refused to approve production orders, threw gun inventors out of his office, and repeatedly slow-tracked Lincoln’s orders. Lincoln couldn’t fire him, because Ripley had powerful friends on Capitol Hill. The delays and the threat of a patent suit sunk Marsh’s gun and his company, rendering him and his weapon a footnote to history. And what would have been the largest order for breech-loading rifles to that point was never fulfilled.

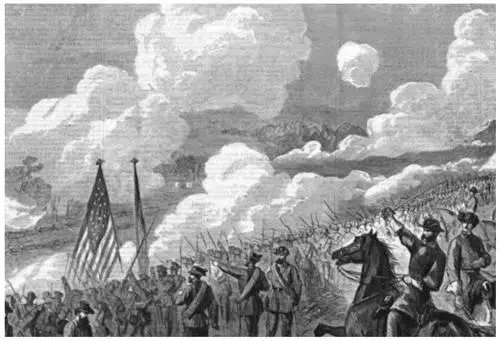

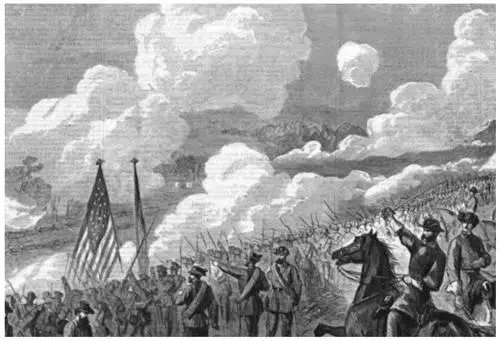

Ambrose Burnside leads Union forces at Bull Run, 1861. The blinding layer of smoke was typical of Civil War battles fought with black-powder muskets.

Library of Congress

Some historians accuse Ripley of dooming many thousands of American troops to unnecessary carnage and death by prolonging the war. I’m inclined to agree. Thanks to the untalented Mr. Ripley, hardly any breechloaders or repeaters were in the hands of Union forces by the end of 1862, a full year and a half after the President’s early tests. Pretty much the only repeaters in Unions hands at all came from a small order for Spencers by the Navy, which was out of Ripley’s reach, and the guns soldiers bought themselves.

I suppose you could take Ripley’s side by saying he had no way of knowing how long the war would go, or what gun platforms would gain traction. Besides worrying about paying for everything—a unique and unusual concern for a government official, in my experience—he was also trying to avoid the headache of figuring out new supply pipelines to feed multiple forms of ammunition to the far-flung troops.

But let’s face it: the guy was a threat to national security.

Luckily for America, Lincoln eventually managed to fire him, aided in part by an anti-Ripley revolt that erupted in 1862 as some units demanded to be armed with the latest guns, especially the Sharps rifle.

The Sharps was a breech-loading, single-shot, percussion-cap rifle that a trained soldier could load and fire up to ten times a minute, or three times faster than a Springfield. A sleek forty-seven inches long, a trained marksman could reliably hit targets at six hundred yards or more with it. The gun was easy to handle and reliable, and it became a favorite of civilians as well as professionals heading toward the frontier. “The Sharps mechanism made the gun so easy to use, anyone could fire it and stand a fairly good chance of hitting something—or someone,” wrote historian Alexander Rose.

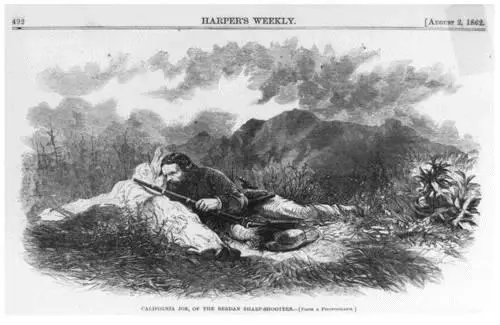

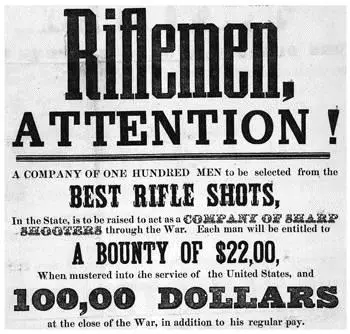

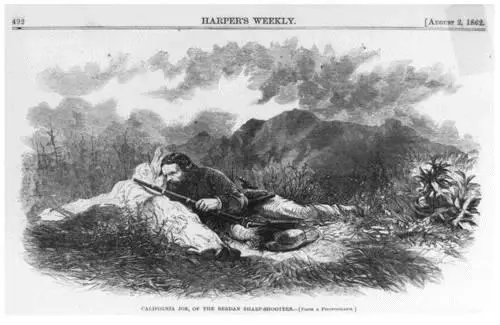

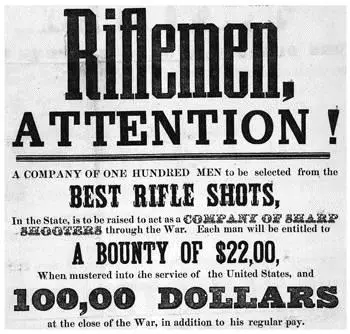

The most celebrated member of Berdan’s Sharpshooters, “California Joe” (aka Truman Head), and his 1859 Sharps rifle. Below: A Union recruiting poster seeking “the best rifle shots.”

Library of Congress

Even more popular in the Army was a carbine version, which featured a shorter barrel—which is, after all, the main difference between a “rifle” and a “carbine.” The highly accurate and easy-to-carry weapon was a favorite with mounted cavalry, both North and South. It should be said that one of the reasons the Sharps was liked by soldiers was its reliability. The gun was well-designed and well-made. The quality of manufacturing was one reason for the higher price; you get what you pay for. Ripley might not have thought so, but the less-well-produced Southern clones proved the point. They didn’t hold up nearly as well.

That’s one of the things historians are talking about when they write that the North’s manufacturing abilities won the war. The days of hand-built guns were past. Armies were now too big to be supplied by a handful of craftsmen toiling away in local workshops. An industrial base and skilled factory workers were nearly as important to winning a battle as great generals were.

The precision of the Sharps meant that marksmen could play an important role in the battle. Special units were created. Among the most effective were Colonel Hiram Berdan’s 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters regiments, whose weapons of choice were the Sharps rifles. These specialized, highly trained marksmen, skirmishers, and long-range snipers wore green camouflage, and, thanks to the easy-loading Sharps design, shot safely from concealed positions, such as flat on the ground or from behind trees. They also carried rifles equipped with the earliest telescopic sights.

To qualify to join the elite unit, you had to be able to put ten shots inside a ten-inch-wide circle from two hundred yards. The Sharpshooters gave the Union army a powerful combat edge and fought effectively in many major battles of the Civil War, including Mechanicsville, Gaines’s Mill, the Second Battle of Bull Run, Shepherdstown, Antietam, Gettysburg, Yorktown, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Atlanta, Spotsylvania, and Petersburg.

But as fine a weapon as the Sharps and other breechloaders from the period may have been, in my opinion the real badass infantry weapon of the Civil War was the Spencer Repeater. And in early 1863, it made its first big appearance on the battlefield. It was a shocking debut.

By now, small batches of at least 7,500 Spencers had made it into the regular Army pipeline, and some commanders were even shelling out their own money to equip their units with the gun. One Colonel John T. Wilder of Indiana was so impressed by a field demonstration of Spencers that he lined up a loan from his neighborhood bank to buy more than a thousand Spencer repeating rifles for his “Lightning Brigade” of mounted infantry.

Colonel Wilder’s commander was Major General William S. Rosecrans, whose Army of the Cumberland was tasked to rout the Rebs from Middle Tennessee. Though slow to move against Confederate General Braxton Bragg and his Army of Tennessee, once Rosecrans got moving he did so with style. In the last days of spring 1863, Rosecrans began a series of maneuvers that are still studied today for their near flawless execution. Wilder and his men, now armed with those Spencers he financed, were smack in the middle.

Читать дальше