So why didn’t everyone use rifles, given their superior accuracy? The biggest problem had to do with how all guns were loaded in those days—through the muzzle. Pushing a bullet straight down a smooth, or nearly smooth, tube is a heck of a lot easier than getting it past one that’s rifled, particularly after the fouling caused by firing several rounds without time to clean. Now, I’ll give it to you that someone like our friend Murph could get the job done quickly under battle conditions, but Sergeant Murphy and his fellow riflemen were master marksmen, and something of an exception. They also had the advantage of not having to coordinate their fire (shooting on command in one group). A line of riflemen working at different paces would be quickly decimated by the most ragged row of musketmen all firing at the same time. They would load their weapons slower, and without time to clean them, have guns much more likely to jam.

Finally, while they were shorter, muskets generally had the advantage of being outfitted with bayonets. Rifles, originally designed for an entirely different type of job, did not. In many if not all battles, bayonet charges proved more deadly and more decisive than several rounds of gunfire.

But used in the right circumstances, a precision weapon like the rifle could be quite important. Traditionally, snipers have been deployed to take high-value targets at long range. And that’s exactly how they were employed in the Revolutionary War.

Which brings us back to our friend Sergeant Murphy, up there in that tree.

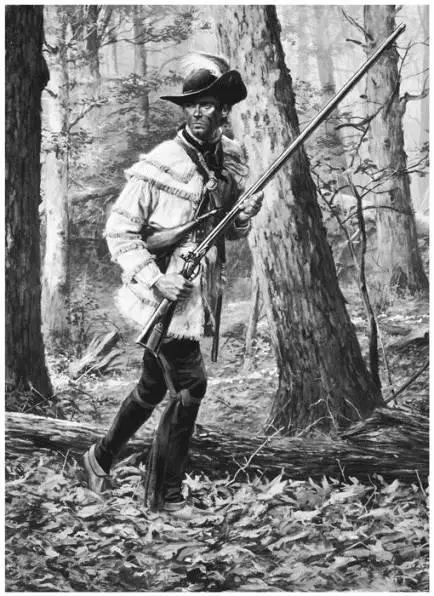

Murphy was a member of an elite brigade of riflemen under the command of Daniel Morgan. Colonel Morgan’s unit specialized in picking off British officers while they mustered their men on the battlefield. The idea was pretty simple: cut off the enemy’s head, and he floundered. The massed firing tactics that were so favorable to muskets depended on good coordination, which generally could only be provided by the officers in the field.

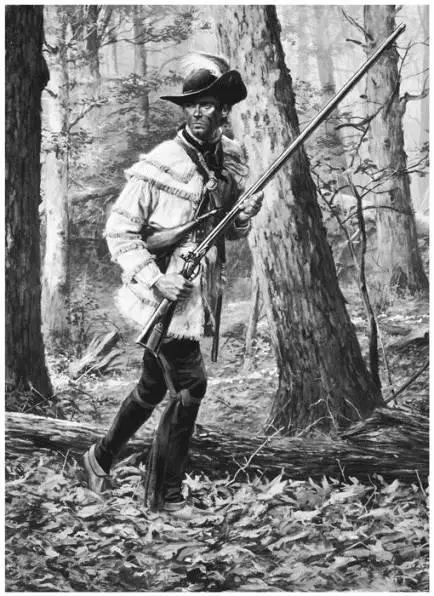

A member of Morgan’s Riflemen, with his tool: the American long rifle.

Don Troiani ( www.historicalimagebank.com )

Throughout the war, British officers were horrified to see American riflemen like Timothy Murphy intentionally aiming at them. This went beyond even the guerilla tactics that had so decimated the British supply lines down from what is now Canada. To many British officers, deliberately aiming at them rather than firing generally at the mass of men on the front line was nearly akin to a war crime. The upper class that filled the officer ranks had never heard of such behavior before, and they were astounded. To them it seemed repulsive, very un-European tactic.

But it was definitely effective. The British feared the colonial riflemen so much they called them “widow-makers.” The best picture of the American long-riflemen comes from the unfortunate British troops who had to face them in battle. British Army Captain Henry Beaufoy wrote that his combat-hardened troops, “when they understood they were opposed by riflemen, they felt a degree of terror never inspired by general action, from the idea that a rifleman always singled out an individual, who was almost certain of being killed or wounded.” Another British officer reported that an expert rifleman could hit the head of a man at two hundred yards, and if he “were to get perfect aim at 300 yards at me, standing still, he would most undoubtedly hit me unless it were a very windy day.”

But their leaders had not fully absorbed the implications of the tactic, and on this day on the battlefield at Saratoga, several were sitting ducks out in the open, mounted on horses where they could be easily targeted. The most important of them was Simon Fraser, a Scottish aristocrat and British brigadier general who was massing his troops for a fresh charge on what would become known to historians as the Battle of Bemis Heights. Fraser’s commander, General Burgoyne, had launched a desperate attempt to break himself free of the rebels surrounding him. Hoping to lure the Americans into a trap, he sent Fraser against the left side of the American line. If Fraser’s troops could break the Americans’ will, the British might escape westward, and live to fight another day.

The battles at Saratoga have become the subject of legends and not a little propaganda on the part of the participants. But there’s no doubt that Murphy was up in the tree, and it’s more than a little likely that he and a few of his brothers-in-arms spotted General Fraser on horseback as he began rallying his troops for a charge. Murphy would have been about three hundred yards away—a good distance in those days, and probably far enough that Fraser didn’t feel in any danger at that early stage of the war.

As his rifle hammer dropped, Murphy’s firearm’s complex process of ignition unfolded, a fragile procedure that is nowhere near as fast as the firing of a modern cartridge arm. Murphy held steady throughout that long second and a half. He handled the gun like it was an extension of himself, and when loading it would have made sure to use the most efficient charge possible. The bullet would have made a sharp crack as it flew, its sonic reflections echoing against the nearby trees and ground.

It missed, though. Instead of hitting the general, it lightly nicked his horse.

Sergeant Murphy pulled a catch to flip up the preloaded bottom barrel. He performed a quick series of complex mental calculations, trying to adjust his aim for wind, altitude, and for the inevitable vertical and lateral drift of the bullet, which at this far distance could be severe.

Then he fired again. The second bullet missed, this one also barely clipping the general’s horse. I imagine he had some choice words going through his head. Nothing bad on Murphy—we all miss sometimes.

At this point, Murphy either would have paused to begin the time-consuming process of reloading his flintlock long rifle, which even for a crack shot like Murphy could have taken as long as thirty seconds, or more likely, someone would have passed him up another, preloaded long rifle.

In any event, Sergeant Timothy Murphy sighted down his barrel for a third shot, then squeezed the trigger. The bullet flew. Legend has it that this one found its target, squarely hitting Fraser in his midsection. In those days, a gut shot was both painful and nearly always fatal. Fraser slipped from his horse, mortally wounded.

Although it’s difficult if not downright impossible to definitively know whether it was Murphy’s bullet that struck the British general, one person above all apparently credited him with the kill: Fraser himself. Taken away to safety too late by two of his aides, the British officer spoke of seeing the American rifleman who shot him, far off in the distance, sitting in a tree.

Fraser’s death marked the final turning point of the battle. It deprived Burgoyne of his best lieutenant, and shortly after he was shot, the British troops fell back in retreat. Burgoyne’s position was now hopeless. Ten days later, he and six thousand British troops surrendered to the Americans, handing them a critical victory. Impressed, the French soon pitched in to offer crucial help to the Americans.

Sergeant Murphy’s boss, Daniel Morgan, is probably a guy you never learned about in history class, but he is one interesting character. He quit the Army after Saratoga because he felt he was passed over for a promotion. But he was soon back in action, and finally received his appointment to brigadier general in 1780. A short time later, he became one of the Revolution’s most important generals, one of the guys we probably couldn’t have won independence without.

Читать дальше