Murphy aimed, and fired….

While that bullet is sailing toward General Fraser—carrying with it the fate not just of the battle but maybe the entire American Revolution—let’s take a look at the weapon that fired it.

American long rifles were adapted for the demands of the New World from designs first produced by European-born gunsmiths in the 1620s. These had grown from the shorter-barreled, larger-caliber Swiss-German Jaeger hunting rifle used in the forests of central Europe. The lighter Americanized guns featured barrels of up to four feet, and often were adorned with nicknames and personalized designs and inscriptions. The biggest difference between muskets and rifles was the “rifling” in the barrels. Rifling is the series of spiraling grooves cut into the bore of the barrel, which cause the projectile to spin on its axis. This spinning would give the projectile enough stability to dramatically enhance the overall accuracy of the gun.

Gun-making was small manufacturing at its best. It was literally a cottage industry: you might have a single master with an apprentice or two creating a weapon for a customer he knew very well from church and the local market. It was a downright poetic activity, as John Dillin put it in his 1924 book The Kentucky Rifle: “From a flat bar of soft iron, hand forged into a gun barrel; laboriously bored and rifled with crude tools; fitted with a stock hewn from a maple tree in the neighboring forest; and supplied with a lock hammered to shape on the anvil; an unknown smith, in a shop long since silent, fashioned a rifle which changed the whole course of world history; made possible the settlement of a continent; and ultimately freed our country of foreign domination. Light in weight; graceful in line; economical in consumption of powder and lead; fatally precise; distinctly American; it sprang into immediate popularity; and for a hundred years was a model often slightly varied but never radically changed.”

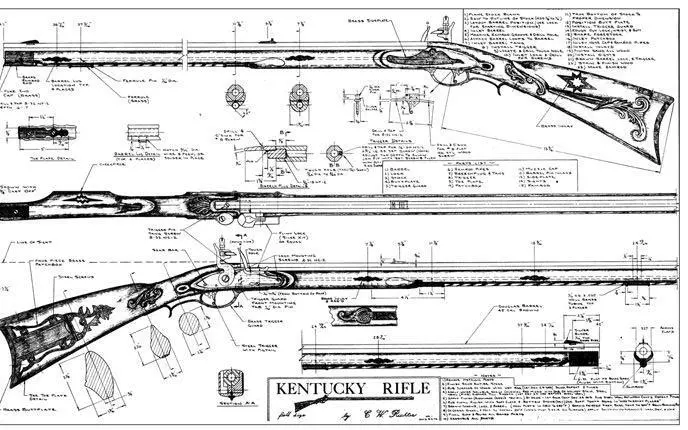

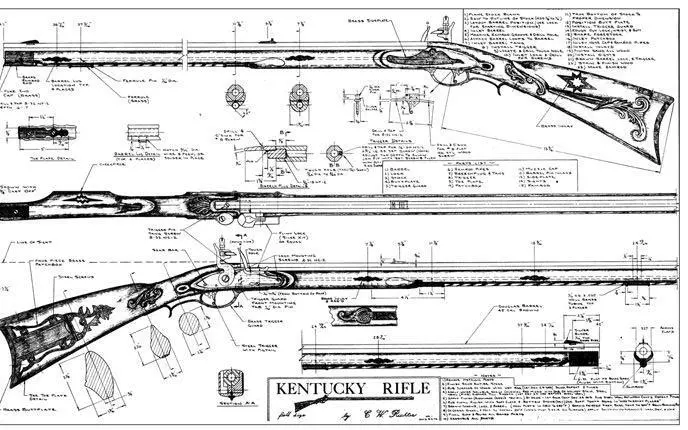

Diagrams of a Kentucky rifle, aka the American long rifle.

Library of Congress

The long rifle was so called because of its lengthy rifled barrel. It was also known as “the Kentucky rifle” (“Kentucky” was once the catch-all word used to describe much of the little-known western wilderness of the Appalachians and beyond) and “the Pennsylvania rifle” (Lancaster and other Pennsylvania towns were a Silicon Valley of innovation and creativity for gunmakers in the 1700s).

When I first fired a vintage “black-powder” flintlock long rifle, I was struck by two things. As a Navy SEAL sniper, I was used to handling weapons weighing in the area of fifteen or sixteen pounds. But the typical American long rifle was around nine pounds, a sleek, surprisingly lightweight gun, more like a precision combat surgical instrument than a battlefield weapon. The process of firing the gun, on the other hand, is incredibly slow. You line up your shot through the superb sighting system and pull the trigger. Sparks shower as the flint strikes the frizzen pan. There’s a quick flash as the sparks ignite the powder in the pan, and a delayed sensation of contact in the gun. A little bit of smoke puffs from the pan as it ignites. A flash of flame passes through a hole into the breech of the barrel, which kicks off the powder charge behind the patched lead ball. Then a mass of gray smoke blasts out of the end of the barrel. The smoke fills the shooter’s whole field of vision. The rifle is so light that the recoil feels more like a push against the shoulder.

Long rifles were first designed and used primarily to kill small-to-medium-sized game on the frontier. Precision was at a premium—a rabbit or deer gave a hunter a relatively short time to fire; by the time you got the weapon reloaded, it would be gone. But rifles would also prove their worth against Indian raids. The bullet—actually a round ball anywhere from .25 to .75 caliber, though usually around .40 to .50—could do a good piece of damage to any target.

(Should I explain what we mean by caliber? In theory it’s the measurement of the barrel’s bore diameter, or in a rifle the size of the grooved interior hole, expressed in fractions of an inch—for instance, 32/100s of an inch equals .32 caliber. But when we’re talking about guns in the Revolutionary War era, it’s best to remember that the measurements and calibers were not anywhere near as standard as they are today. Bullet making was as much of an art as gun making; precision standardization and mass production were about a hundred years in the future.)

The weapon’s longer barrel—extending from 35 inches to over 48 inches (compared to some 30 inches for the average musket)—gave the black powder extra time to burn, boosting the rifle’s accuracy and velocity. The long rifle had adjustable sights for long-distance accuracy; like modern rifles, the gun would be “sighted in” by its owner, tuning it not only to his needs and circumstances, but the weapon’s own distinct personality.

Since they were made by hand, no two long rifles were exactly alike. Granted, the majority might appear very similar to anyone except their rightful owner. But look closer, and each weapon’s uniqueness became obvious. Small variations in the wood furniture or the fittings were of course to be expected. Much larger innovations were also common—Sergeant Murphy, for instance, was believed to have had a double-barreled rifle. It was an over-under design, with one barrel above the other. The arrangement would have made it quicker for him to get off a second shot, a key asset in battle as well as hunting.

Warfare in the late eighteenth century was dominated by a very different gun, the smooth-bore musket. While the firing mechanisms used by muskets and rifles were pretty much the same, the barrels were decidedly not. As the name implies, a smooth-bore musket had a barrel that was smooth, not rifled; fire the gun and its bullet traveled down the tube as quick as it could. By design, the bullet was smaller than the inside of the barrel. This was necessary because deposits of burnt powder and cartridge tended to form on the inside as the weapon was fired. Gunmakers had learned from experience that under battlefield conditions, too tight a fit might lead to the gun misfiring—not a good situation. They designed their bullets to be snug, but not tight.

There was a downside to that. A bullet flying from a musket could only go so far on a given charge. Some of its energy was wasted in that open space around the ball. It also wasn’t necessarily that accurate. The farther the bullet got from the gun, the more likely it was to move in any direction but the one the shooter intended. Now, this wasn’t a problem at ten feet. But put yourself on a battlefield and engage an army at a few hundred yards, and you begin to see the limitations. Still, the musket was a considerable weapon. Contemporary tactics were organized around it; that’s why you see all those lines of soldiers in the historic paintings and reenactments. Truth be told, every important battle in the Revolution centered around those lines of men and their muskets.

The firearms the British used were generally Land Pattern Muskets, known informally as the “Brown Bess.” There were a number of variations on the same basic design; the most important was the Short Land Pattern, used by cavalry and other horsemen. Oftentimes, especially early in the war, the Americans used the Brown Bess, too. Later the French shipped large numbers of their various Charleville models. Like the long rifle, the muskets were flintlocks. Pulling the trigger released the flint to strike the frizzen; the spark ignited the gunpowder in the barrel and off went the bullet.

Читать дальше