That was all going to change. America was becoming a different place. And the police were the ones who’d be caught in the middle.

The first full-fledged municipal police force in America was started in New York City in 1844. The police started carrying pistols in the late 1850s. For the next forty years or so, they armed themselves with a hodgepodge of guns. The officers got about as much training as a SEAL gets dance lessons. When he came on as police commissioner, Teddy Roosevelt made the .32-caliber Colt New Police revolver the regulation police handgun. He also set up a marksmanship program, led by national shooting champion Sergeant William Petty.

Other big cities moved in the same direction. They were all dealing with similar problems: booming population, crowded living conditions, corruption, vice, immigration, criminal gangs—the entire dark side of an increasingly urban nation.

Once police departments decided to arm their officers, they faced difficulties armies don’t have. Like the military, they needed weapons that were dependable and could stop a bad guy cold. But whatever they picked had to be suited to everyone on the force, big or small. That might not seem like much when a police force has mostly oversized Irishmen who like to crack heads, but step away from the cliché to modern forces with officers of every size, shape, and gender, and you see the dimensions of the problem.

In “traditional” warfare, armies didn’t waste much thought worrying about civilians getting hurt. Police departments, on the other hand, spend all their time around civilians. They have to suit their weapons to the threat they face, but not go overboard. A bullet that stops a criminal and then goes into the next building can turn a clean collar into a tragedy.

Even in the worst crime pits, most police officers never have to fire on a suspect. Many officers usually only fire a handful of times in their career, if that. So they need guns handy, but still tucked away. Last and not least, whatever they get has to be inexpensive. Not cheap, but a good value. A buddy of mine from San Diego, Mark Hanten, is the commanding officer of the SDPD SWAT team. Mark pointed out recently that his department has some eighteen-hundred-plus cops, and some, like the LAPD, well over eight thousand. Buying a weapon for all of them can put quite a dent in the taxpayers’ pockets.

The money isn’t just in the weapons. The officers need ammo, both to use the gun and, just as important, to practice with. And practice takes time—every hour a policeman spends on the firing range is one less hour on the street, which means someone else has to do his job there.

So police weapons evolved toward efficiency, and just enough stopping power to get the job done. While rifles, shotguns, and automatic weapons fill certain roles, the sum of what a policeman needed meant a pistol would be his primary weapon. And if you were thinking about a pistol for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, odds are you were calling to mind a product from one of two companies: Colt, or its chief competitor, Smith & Wesson.

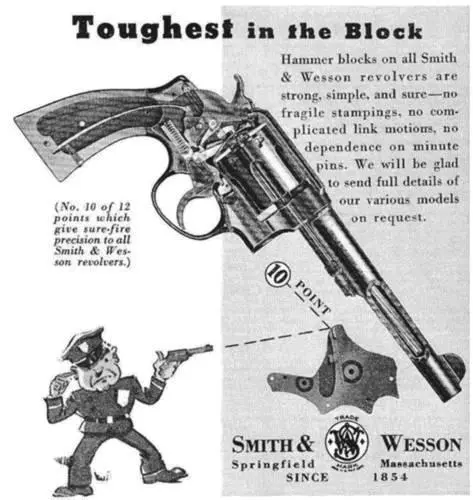

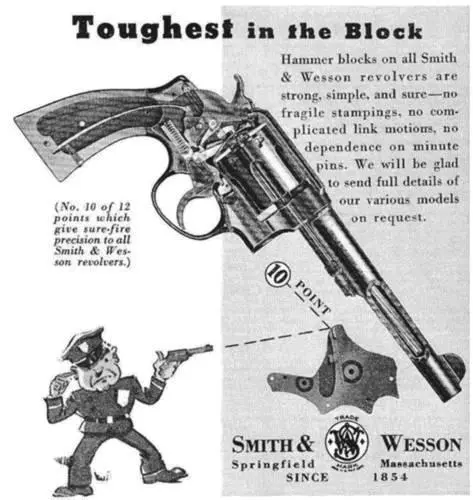

Colt scored big with their revolvers in the mid-nineteenth century, but Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson were right up there with them. The New England gunmakers teamed up in 1852 in a failed attempt to launch the lever-action “Volcanic” repeating pistol and rifle with a fully self-contained cartridge. As we’ve seen, the business flopped and Oliver Winchester ended up with the company. But Smith and Wesson didn’t ride off into the sunset. The pair patented a rimfire cartridge in 1854, then used it to design a new revolver. In 1856, their new company, Smith & Wesson, unveiled the Model One Revolver. The .22-caliber seven-shooter launched the company on a road that would include a number of historic guns.

Coke versus Pepsi, Chevy versus Ford, Colt versus Smith & Wesson: the all-American pair duked it out for decades. Their guns got better thanks to old-fashioned competition. After making improved versions of the Model One, Smith & Wesson topped itself in 1867 with the Model 3 .44, the first big-bore cartridge-firing revolver. Colt came back with the classic Single-Action Army revolver of 1873. Then they followed up with the first successful double-action revolver, the Model 1877. In 1889, Colt unveiled a new line of Army and Navy revolvers, the first double-action revolvers with swing-out cylinders.

Smith & Wesson

On a swing-out frame, the cylinder pivots away from the body, making it faster to load than a fixed frame gun. At the same time, the frame is stronger than the break-top, a design which also makes for quick reloading by letting the cylinder and the front of the gun forward.

In 1899, Smith & Wesson came out with Model 10, also known as the Military and Police revolver. Colt followed with the New Police, the Police Positive, and then the Colt Official Police.

The weapons from both companies have a lot in common. Together they defined the category of police handgun, and even the word “revolver” for sixty or seventy years. And through most of that time, they shared one critical ingredient: the .38 Special cartridge.

The family of .38-caliber bullets can be almost as confusing as the guns that use them. It probably won’t help to mention that the rounds were first supplied to replace the old ammo used by .36-caliber Navy revolvers. It especially won’t help to point out that the .38 round’s diameter is really .357—exactly because of that heritage. But those are the facts. The family includes the .38 Special, the .38 Short, .38 Long, and .357 Magnum, all at the same diameter. There are a bunch of cousins and near-strangers under each heading.

The .38 Special cartridge was one answer to the question of how to stop raging maniacs, the same problem the Colt 1911 was invented to solve. The .38 Special was more powerful than the .38 Long, which was a bit stronger than the .38 Short. First filled with black powder, smokeless powder became the standard about a year later. The .38 Special cartridges packed enough wallop for a while. But when stopping power became an issue again, improvements led to the .38 Special +P and .357 Magnum rounds.

Colt’s history gave it a leg up in the police market. The Colt 1911 also helped with what marketers call a halo effect. It was like Ford or Chevy with NASCAR. Associating with a wartime hero made the other guns look that much better.

But it wasn’t just the weapon’s marketing that made it popular. “As a personal defense weapon, Colt’s Official Police with a four-inch barrel is as dependable a gun as you could find,” wrote police weapons expert Chic Gaylord. “The Colt Official Police revolver in .38 Special caliber with a four inch barrel and rounded butt is an ideal service weapon for densely populated metropolitan areas. The Colt Official Police is probably the most famous police service arm in the world. It is rugged, dependable, and thoroughly tested by time. It has good sights and a smooth, trouble-free action. This gun can fire high-speed armor-piercing loads. It can safely handle hand loads that would turn its competitors into flying shards of steel. When loaded with the Winchester Western 200-grain Super Police loads, it is an effective man-stopper.”

By 1933 the Colt Official Police was standard issue for the police forces of New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Kansas City, St. Louis, and Los Angeles, plus the state police of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and Connecticut. The FBI issued the gun to its agents.

The standard pistols were meant to be carried in holsters at a policeman’s hip, and had barrel lengths varied from four to six inches. As a general rule, the longer the barrel, the more accurate the gun was likely to be in the average policeman’s hands. On the other hand, the longer the barrel, the harder it was to get out of the holster.

Читать дальше