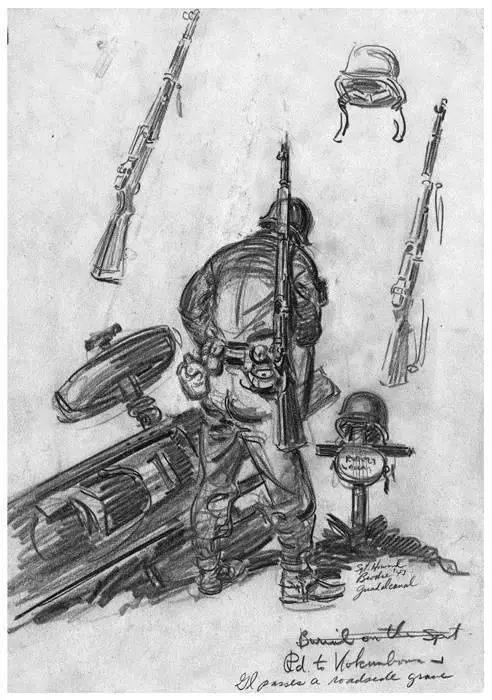

“G.I. passes a roadside grave,” a battlefield sketch with M1 Garands. Guadalcanal, 1943.

Library of Congress

On Guadalcanal, in a slow, grinding struggle, the American soldiers and Marines expelled the Japanese in February 1943.

It was an important turning point in the war. The American victory, combined with the U.S. Navy’s earlier success at Coral Sea and Midway, shifted the momentum against the Japanese. They would never recover it.

“Guadalcanal is no longer merely a name of an island in Japanese military history,” said Japanese infantry commander Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi. “It is the name of the graveyard of the Japanese army.”

In the European Theater, the M1 Garand offered U.S. infantrymen three more shots and less time between them than the standard German Karabiner K98 Mauser rifle. The Germans tried pretty hard to find a suitable semi-auto replacement for their bolt-guns, but couldn’t quite hit the sweet spot with anything. So the K98s remained the main thing in German hands when they came up against Americans.

That’s not to say that some of the German guns, including the Karabiner K98, weren’t impressive. As a matter of fact, most people credit the Nazi StG44 with being the first assault rifle ever. That gun seems to have influenced the famous AK47, though the AK is a very different beast. And our M60 machine gun owes a lot to the German MG42, a battlefield bulldog that pretty much defined the term “suppressive fire.” But as far as rifles went, the M1 was better than anything the Germans were fielding in serious numbers during the war.

The thing that seems to have impressed American soldiers the most wasn’t the M1’s accuracy or even the number of rounds it could fire. John Garand’s baby was just as tough as they were, and cared about as much as they did for creature comforts. Which is a good thing, because they don’t call war “being in the shit” for nothing.

“The most amazing thing about that M1 is you could throw that thing down in a mud hole, drag it through it, pick it up and it would fire,” said Darrell “Shifty” Powers. He was one of the famous “Band of Brothers” of E Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division “It wouldn’t jam; it would fire. What we did mostly was keep the outside of it as clean as we could with a rag or something. And we’d clean the bore out as often as we could. Any time we were off the line we’d clean the rifles well. In combat, when you were right on the line you don’t take time out to clean the rifle. You just kept the mud and dirt wiped off the outside of it the best you can. They were outstanding weapons, that rifle worked all the time.”

Interviews with German prisoners revealed that many of them were spooked by the superior firepower delivered by the Americans’ M1 Garands. They were sometimes mistaken by green German infantrymen to be portable and terribly accurate high-powered machine guns.

The Battle of the Bulge, which started with a surprise attack in mid-December 1944, was Hitler’s last-ditch counteroffensive to try to stop the Allied express. The Germans massed the best of their divisions along the Western front, which roughly coincided with the German border, then tried to drive a wedge through the American line. The plan was like a Hail Mary with ten seconds to go in a football game, but given where Germany found itself, they had to take some sort of gamble or just give up.

At first, the Nazis kicked the Americans all through the Ardennes Forest. The XLVII (47th) Panzer Corps ran through the weak sector in Omar Bradley’s armies, punching so deeply into Belgium that Eisenhower thought he’d have to retreat to the other side of the Meuse. One of the reasons that didn’t happen was the arrival of the 101st Airborne at the little crossroads town of Bastogne. The paratroopers, who’d just spent several weeks slugging through Holland, were supposed to be getting a little R&R. Instead, they were packed into trucks and driven to Belgium, where they were told to hold a key crossroad in front of the German advance. They were just about surrounded on December 22 when the German corps commander, General der Panzertruppe Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, gave them an offer he didn’t think they could refuse: surrender, or we’ll bulldoze you.

Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe made his answer short and sweet:

“To the German Commander,

Nuts!

—The American Commander.”

The Germans probably had a little trouble translating that until the paratroopers helped out with some precision M1 shots from their hunkered-down positions.

Bastogne was relieved on December 26 when advance units from George Patton’s army, diverted north by Bradley, punched through the German troops surrounding them. The German advance was running out of gas, but the Wehrmacht was not about to retreat without a fight. Bad weather and bad blood between the British and American commanders under Eisenhower hampered the counterstroke. When it finally got under way, it slogged slowly through frozen terrain. The Germans, their backs to their border, fought like cornered wolves.

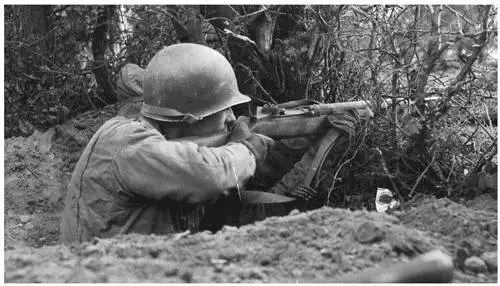

An American aims his Garand at a Nazi.

National Archives

Private Joseph M. Cicchinelli was part of A Company, 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion attached to the 82nd Airborne Division, near the Belgian village of Dairomont. Though the 82nd never got the press the 101st did, they had also rushed to the rescue at the start of the Battle of the Bulge. Holding the line on the northern side of the German advance, they had just as important a job, and took as bad a beating in some places.

As the Americans went from defense to offense, the unit joined the counterattack. Cicchinelli’s platoon was told to take Dairomont, one of a series of small towns commanding the crossroads south of Spa and Leige. The woods were filled with snow and dead soldiers on both sides. It was so cold a private was discovered frozen to death that morning. Supplies were low; some guys hadn’t eaten in two days.

The battalion commander ordered a frontal attack on the village. The Americans poured M1 and Thompson submachine gun fire at German positions, but their attack stalled. There was the danger of friendly fire as two squads encircled and rushed the enemy from two different directions in the late afternoon fog. So platoon leader Second Lieutenant Dick Durkee ordered a desperate maneuver.

“Fix bayonets!” came the command. The men pulled bayonets out and snapped them below the muzzles of their M1s.

Thirty American soldiers charged through knee-deep snow toward a German machine-gun nest. The position was guarded by foxholes. Durkee reached the first foxhole, swung his rifle around, and cracked an enemy soldier on the head with the butt end of his Garand. Then he moved on to the next. “We reached the enemy position, and leaped from foxhole to foxhole, thrusting our bayonets into the startled Germans,” Cicchinelli remembered.

In less than thirty minutes of hand-to-hand combat, sixty-four Nazis were dead.

Some Germans thrust their hands up to surrender, but “they never had a chance,” recalled Durkee. “The men, having seen so many of their buddies killed and wounded during the past twenty-four hours, were not in a forgiving mood.” By the time the fighting was over, thirty half-frozen, half-starving American GIs with bayonet-tipped M1 Garands had liberated the village of Dairomont.

Читать дальше