The rifle—that was something special as well. It was the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1,” a ten-pound, eighty-five-dollar, gas-operated, air-cooled, clip-fed semi-automatic. It was new to the unit—Koons had only just wiped off the heavy protective grease it had been shipped in the other day. But it would soon prove to be one of the finest guns ever made.

The M1 Garand has been called “the gun that saved the world,” and that’s not an exaggeration. The rifle is without a doubt the most important in modern American history. To the Greatest Generation, and even their kids, the M1 defined the word “rifle.”

It was created by John Cantius Garand, a quiet, humble gun designer who worked for the U.S. government’s Springfield Armory, in Massachusetts.

Garand was a native Canadian who, like a lot of gun designers, was a little odd. It’s said he used to flood his basement during the winter so he could skate there after work.

Good thing he didn’t live in Texas.

After World War I, the Army realized that a semi-automatic or self-loading rifle would give whoever used it a great advantage. Of course, being the Army, they wanted the weapon to be all things to all people—it had to be light, had to be accurate, and it had to take more abuse than a mule in winter.

The smartest thing the Army did was hire a bunch of people, including Garand, and told them to have at it. Garand had been discovered, more or less, because of a design for a machine gun he’d invented. It was an interesting arrangement: When fired, the primer moved back and hit the firing pin, which came back and unlocked the bolt. A cam and a spring combination kicked out the shell and brought in a new cartridge. It was different than any other mechanism around, and even more complicated than it sounds. But it did work—just not well enough to beat out other designs.

Garand tried using the same mechanism in a semi-automatic rifle. That performed a little better. But he didn’t have a breakthrough until he let go of that idea entirely. Instead, he found a way to use the gas generated by the burning powder to do work in the rifle that, till now, had been done by hand or recoil.

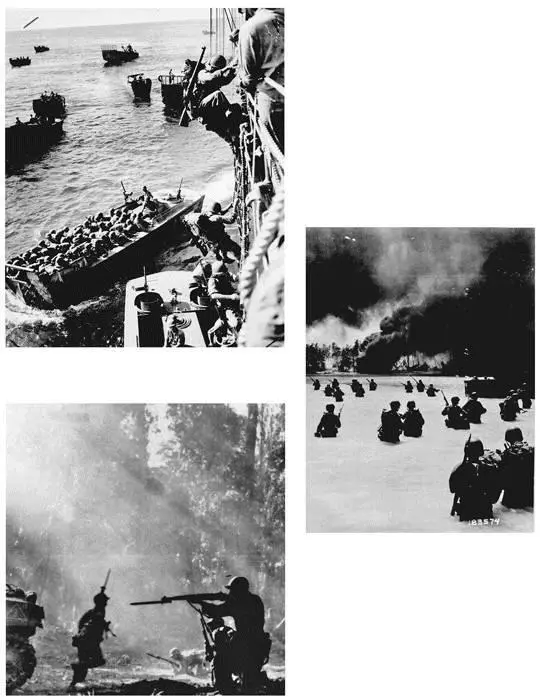

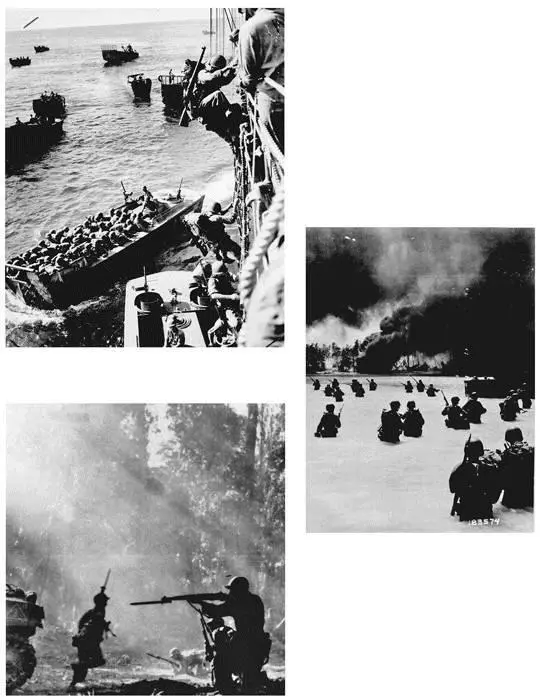

U.S. warriors and their M1 Garands during the Pacific Island campaign.

National Archives

As the bullet in the M1 Garand moves out of the barrel, the gas behind it finds its way to a small port. The pressure of the gas drives a piston back. This moves the operating rod and powers the mechanism that opens the bolt, kicks out a round, and feeds a new one. Cams, lugs, tangs—the mechanical pieces work together like the insides of an old-fashioned watch, but are tough enough to take the pounding and abuse involved in launching something at the speed of sound, or thereabouts.

New developments in powder propellant were key to making it all work, since the gas had to be produced in a certain volume and pressure. (Slow and steady in this design was better than all-at-once quick.)

Garand was not the first person to think of the idea. Browning had been there before, and the principle was being used for machine guns. Garand got it to work in a semi-automatic rifle that could be mass-produced. His willingness to think about problems in a whole different direction put rifles on a new course.

While Garand was developing his designs, another genius, also a little peculiar, was working on his own project. John D. Pedersen’s semi-automatic rifle had a different, more complicated mechanism. It also used a .276 caliber round. There were a few advantages to using the smaller cartridge in an infantry rifle, including weight and wear on the gun. Not to get too technical here, but one of the interesting sidelights of the workup on bullets for the new rifle showed that smaller bullets could do more damage at certain distances than the .30-06. That’s a point to remember down the line.

Garand first produced his gun in .30 caliber. Then the Army brass heard the arguments in favor of the smaller rounds and decided the next infantry rifle should be chambered for .276. So he went back to the workbench and came up with a .276 version.

It was better than the .30. In fact, it was better than Pedersen’s, too. The Garand .276 was easier to manufacture, and less prone to breakdown, at least according to the tests.

That’s when Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur stepped in. General MacArthur insisted that the next infantry rifle, whatever it might be, should be chambered in .30-06.

He didn’t do it because of the bullet’s impressive accuracy, range, or superior stopping power. Rather, the Army had been kicked in the gut with budget cuts, and adopting a gun with the same bullet they’d been using for twenty years was a lot cheaper than the alternative. It was the middle of the Depression, and things were tough everywhere.

There’s a bright spot in every cloud.

It took a few more years to actually perfect the .30-06 version of Garand’s gun, but the M1 Garand was offically tapped as the Army’s rifle on January 9, 1936. Getting it into the hands of soldiers would take longer still—but it did get there. The rest, as we say, is history.

The M1 Garand was the world’s first semi-automatic rifle issued as standard weapon to any army. It boosted the combat power of the American fighting man over his enemies, who at that point were pretty much all armed with World War I–type bolt-action rifles. The Japanese, for example, mostly used the Arisaka Type 99. The Type 99 was modeled after the Mauser and held only five rounds.

To load the M1, a soldier locks the bolt by pulling the operator rod on the side back. He wants to give it a good tug, making sure it locks; if he’s gentle there’s a chance the mechanism will slide back forward later and try and grab his thumb. He then takes the eight-round clip and pushes it down with some authority into the receiver. The bullets click into place. He removes his thumb—loading is always supposed to be done with the thumb, according to the manual and the old instructors. The bolt slaps forward.

Top: the M1 Garand and its eight-round en-bloc clip. Middle: John Garand (left) presents his weapon to the U.S. Army’s Chief of Ordnance (middle) and the commanding officer of the Springfield Armory (right). Bottom: M1s being loaded for the front; by 1944, almost 4,000 were being produced a day.

Wikipedia (top); Library of Congress (middle and bottom)

Done. The first round is chambered and the gun is ready to go. From that point, the soldier can fire as quickly as he can pull the trigger. When the bullets are gone, the clip is ejected with a loud ping. The rifle is singing for new rounds.

General George Patton called the M1 “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” Historian William Hallahan described the Garand as “one weapon that outgunned its counterparts in every other army in the field.” It was tough and dependable no matter where or how it was used. “In surf and sand, dragged through the mud and rain of tropical rain forests, sunbaked, caked with volcanic ash, covered with European snows that melted, then refroze inside the breech, beset by rust and mildew, mold and dirt, the Garand still came out shooting.”

Читать дальше