But it held up. Police and military buyers around the world subjected the Glock 17 to torture tests. The gun aced them. You can submerge it, subject it to high temperatures and massive sequences of firing, and the thing just keeps on working. The Glock is so rugged that some salesmen drop it on the floor to impress customers.

Glock bagged the Austrian army contract, and a firearms empire was born. American police and military officers loved the new black-plastic gun, and started swamping the company with orders starting in the late 1980s. Glock gave excellent trial discounts to the police. “This was smart,” noted author Paul Barrett, “because the point was to get the police departments to adopt the gun, and that would give the gun credibility in the much larger, much more lucrative civilian market, where you can charge full price and get your full profit margin.”

Glocks popped up in Hollywood movies and rap songs. It became a pop culture hit. It also found its way to criminals, who liked the Glocks for much the same reasons the law did.

There’s an urban myth, still popular in some quarters, that the Glock can’t be detected by X-ray machines. The myth was spread by a Bruce Willis line in the 1990 movie Die Hard 2: “That punk pulled a Glock 7 on me. You know what that is? It’s a porcelain gun, made in Germany. Doesn’t show up on your airport X-ray machines.” Every bit of the line was false: there was no such thing as a “Glock 7”; Glocks are made of polymer, not porcelain; it was made in Austria, not Germany; and they do show up on X-ray machines. But in a strange twist, the firestorm of controversy triggered by the false rumors may have helped goose publicity and aid Glock sales.

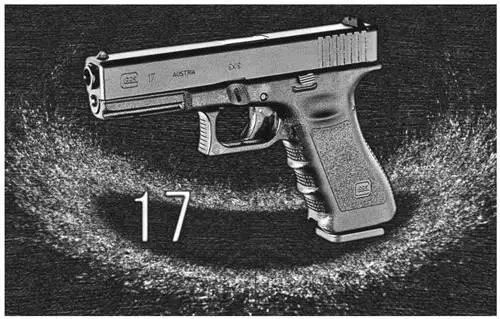

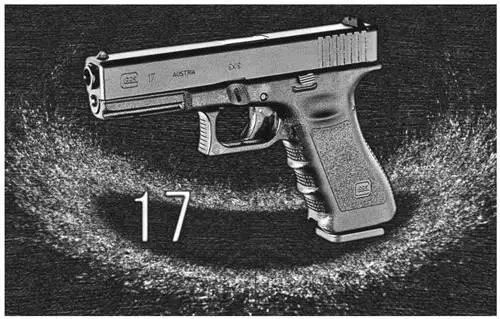

Above: The iconic Glock 17. Below: On the right, taking it for a test-drive at a range in Poland.

Glock Ges.m.b.H (top); Robert Kowalewski (bottom)

Today, more than four million Glocks have been sold, and at least two-thirds of American police departments use Glocks, including the nation’s biggest, the NYPD, plus federal agencies like the FBI and the Drug Enforcement Administration, and some military special-operations units also use Glocks as their standard sidearm.

As for myself, I prefer the M1911. To me, a Glock is about as good-looking as a lump of coal.

I started this chapter with a presidential assassination attempt. It’s hard for a Texan to do that without thinking of Lee Harvey Oswald and that awful day back in 1963 when John F. Kennedy was shot down here. There are still plenty of folks around who were there and remember what all happened.

One of them is Jim Leavelle, who was walking Oswald down the ramp of the garage under police headquarters two days later when Jack Ruby shot him.

Jim, a friend of a friend, was a Dallas police officer for going on twenty-six years. If you’ve ever studied the JFK assassination, or even spent a bit of time looking at the photos, you’ve seen him at Oswald’s right in the light suit on the garage ramp as they walk down to take Oswald to court. Just as they come into view in the famous TV footage, Ruby ducks past an army of reporters and policemen. Leavelle starts to yank Oswald toward him out of the way, but Ruby’s too close. He fires into Oswald’s middle, then gets gang tackled.

Leavelle says he spotted Ruby’s pistol in the half-second after Ruby ducked around one of the other officers near the car. The retired officer is often asked by people why he didn’t shoot Ruby.

“It just happens so fast,” he tells them. “It always does. Sometimes you don’t have time to draw. You just react. That’s all you can do.”

That’s some hard-earned experience talking there. Training helps, good weapons help, but nothing beats dumb luck.

Leavelle was in a bunch of close scrapes over his career. He packed a number of weapons—a lot of .38s in just about every barrel length, a .45 Colt, a .38 Super, a .357 that he thought was a bit too heavy for an everyday carry. The day he escorted Oswald, he had two Colt .45s with him, but never had the chance to use them.

Ruby, by the way, killed Oswald with a .38 Special.

10

THE M16 RIFLE

“Brave soldiers and the M16 brought this victory.”

—Lieutenant Colonel Harold Moore

The world shook as they rode to battle. The sky around them was filled with helicopters. Vietnam was green and light brown, peaceful from a few hundred feet above. But the drum of rotors were the call to war.

The American Hueys squatted into the elephant grass. Dust and dirt flew everywhere. They were in.

“Let’s go!” yelled Lt. Colonel Hal Moore, grabbing his rifle as he leaned to jump out of the bird. “Let’s go.”

It was November 14, 1965. The forty-two-year-old lieutenant colonel was leading the soldiers of 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment into a battle like none the world had ever seen. But as he and his men ran toward the edge of the jungle bordering Landing Zone X-Ray, I’d wager not one of them was contemplating history, or even the new tactics they were employing. They were thinking about their guns, maybe, and staying alive, mostly.

First Battalion had just put down in a remote jungle clearing in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. It was the start of the Battle of Ia Drang Valley, an epic chapter in the Vietnam War.

Ia Drang—pronounced “ja drang”—is famous today as the first combined-arms air assault ever. Never before had a large group of soldiers been airlifted by helicopter and dropped down into battle miles from any support elements, or what you might call a traditional battlefront. Air support—not only from ground-pounders like the A-1 Skyraider but from strategic bombers like the B-52—played a critical role in the battle. The fight was also the first large-scale engagement between the U.S. Army and the People’s Army of Vietnam—the North Vietnamese. It was as close to a “set piece” battle as the conflict ever got.

But Ia Drang was important because of another “first,” one that’s often forgotten today: It was the first time U.S. military personnel waged war with a fully automatic assault rifle as their standard weapon.

The rifle Moore held as he leapt from the helo was a new select-fire gun officially called the XM16E1. Soon to be known as the M16, the weapon had an immediate impact on the way Americans fought. It looked nothing like anything anyone had used in war before. The NVA regulars and Viet Cong took to calling it the “Black Rifle.”

“What we fear most is the B-52 and the new little black weapon,” said one of the Cong captured during the battle.

“The new little black weapon.”

U.S. Army

The Battle of Ia Drang was a baptism of hellfire for the men of the 7th Cavalry and the new M16. When it was over four days later, the U.S. had won. A large number of North Vietnamese had been killed, and they had been chased from the battlefield. But the fight also taught the enemy what tactics might be most useful against American firepower. Americans saw the enemy was tough, and wouldn’t give up easily, even when they were being slaughtered. And maybe most frustrating for regular U.S. GIs, they soon learned that while the new rifle they had was pretty good, it was not yet the weapon it could be.

Читать дальше