Supply flights, having to cross even more unfriendly territory, became less frequent and suffered higher losses. German soldiers on the lines in Stalingrad literally starved when they did not die of exposure first. Ammunition was rationed and medical supplies virtually gone. Then the airstrip was overrun, and the last German plane to land took off again carrying wounded and a few officers on January 23.

By the middle of January, the Sixth Army became a formation that was broken into pockets. The Russians then approached von Paulus with an offer. If he surrendered, his men would be treated well, receive medical help, and be guaranteed repatriation after the war ended. Seeing no chance of escape or victory, von Paulus asked Hitler for permission to surrender. This was Hitler’s reply:

Surrender is forbidden. 6 Army will hold their positions to the last man and the last round and by their heroic endurance will make an unforgettable contribution towards the establishment of a defensive front and the salvation of the Western world.

General von Paulus obeyed and turned down Zhukov’s offer. On January 30, having doomed the army and its commander once more, Hitler promoted von Paulus to field marshal. The Führer then informed the hapless commander that no German field marshal had ever surrendered. Finally, the former staff officer acted on his own. Though by this point the only action left to him was to surrender. He did this, including the men defending his pocket, the next day. Two-thirds of the Germans trapped in Stalingrad had died. The remaining 91,000 had all surrendered by February 2. Of those men, less than 5,000 ever returned alive to Germany, most many years after the war had ended.

Hitler’s mishandling of the Battle of Stalingrad, from appointing a personal favorite but untested commander to twice refusing to allow the army to save itself, cost Germany half a million soldiers. Half a million veteran soldiers would have made France impregnable to an Allied landing or delayed the Russian advance on Berlin for months. The men of the Sixth Panzer Army would be desperately needed as the Soviet war machine pushed west, but they were all lost because of Adolf Hitler’s mistakes.

The Salient Question

1943

The strategy of pinching off a salient, or bulge, created by the last surge of the Soviet army’s central front’s winter offensive was not a bad one. Some action that would punish and slow the relentless advance of the Soviet army was a necessity. Since Stalingrad, the Wehrmacht had been reacting to the Russian army, and they knew that their first priority had to be to get the initiative back. Russian tank production was beginning to peak at so many tanks per month that that German high command did not believe the figures. Worse yet, German production had hit a snag. They had stopped some of the production of their work-horse panzer IVs in favor of building the Panther and Tiger models. A problem was neither of those tanks could be produced in numbers sufficient to replace the Mark IVs lost. In the month that the German tank industry changed over to producing the two new and much more powerful tanks, only twenty-five Tigers were manufactured. The Panthers also continued to have such severe reliability problems that, as Heinz Guderian bluntly noted in his memoir Panzer Leader , they were “simply not ready for the front yet.” But Hitler, seeing the war effort crumbling on every side, put inordinate faith in his new “super weapons,” among these the Panther and Tiger tanks and the ME262 jet fighter/bomber.

There were really only two choices for the German army. Many of the most experienced field commanders, including Erich von Manstein and Heinz Guderian, master of the Blitzkrieg, wanted to continue as they were. This was to use the superior tactics and skills of the German forces by forming mobile reserves that responded to and destroyed every Soviet army penetration. If they could crush enough tanks and their supporting infantry, both the numbers and the skill level of their opponents would fall. Just as in World War I, when the Russian soldiers felt they were being wasted, they revolted.

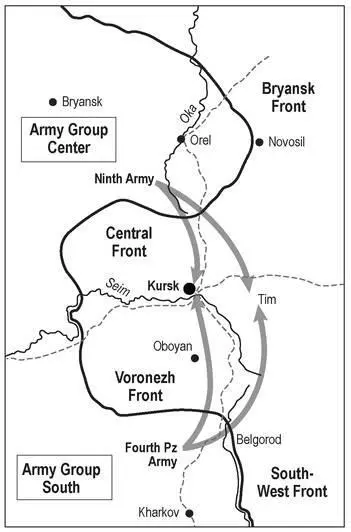

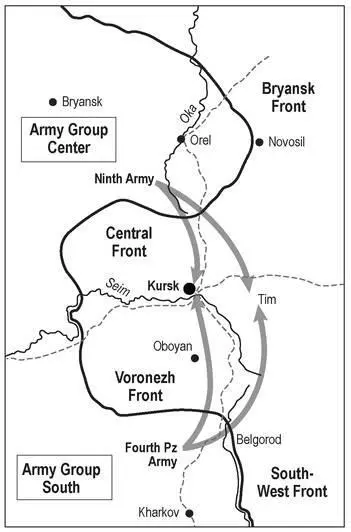

The chief of staff, General Zeitler, had a more ambitious plan. He wanted to return to the sweeping encirclement of 1941. His idea was to draw the Russian army in and destroy them in one large battle. This was, not surprising, a form of the decisive battle fallacy found all through history. He felt that he had found the ideal location for such a confrontation. The Russians had pushed forward into the German position and formed a deep bulge located in almost the center of all of the German positions. On one flank of the penetration, the Wehrmacht held the city of Orel, and on the other, Kharkov. Both cities were major rail centers and so ideal locations for the buildup of forces needed to pinch off the salient. The German armies would encourage the Soviets to place, in or near Kursk, as many tanks and soldiers as possible. Then they would pinch it off by converging on Kursk in the center, trapping so many Russians that their offensive capability would be crippled. This plan is shown on the map (see page 320). The reality would have much shorter lines for the German advances: barely showing in the north and half as long in the south.

Hitler wanted a decisive victory, and one at Kursk both would be dramatic and had a better chance of knocking Russia out of the war. So on May 4, 1943, Hitler decided on Zeitler’s plan, dubbed Operation Citadel, and ordered it be implemented. At this point, it became his plan and so it was sacrosanct and unchangeable by anyone else. The war was going badly on all fronts. Hitler had become, at best, unstable and tended to irrational screaming fits or worse. Just telling him what he did not want to hear was risky. He was still the absolute dictator of the Reich.

The Battle of Kursk

Two problems appeared immediately. The first was that the Russians were already preparing a defense in depth of the salient. Line after defensive line was being prepared with antitank guns, machine guns, and fortifications. The Russian tanks, which were the target of the exercise, were being placed farther back. This meant that before there could be Blitzkrieg, the German panzers would have to slug through miles of fixed defenses. Experienced panzer general von Mellenthin saw the aerial photos of those defenses and correctly described the attack as being a “Totenritt,” a death ride. Field Marshal Guderian tried to get Hitler to cancel the attack. According to Guderian, the Führer admitted that thinking about the plan made his stomach turn, but he refused to cancel it. Hitler wanted a decisive victory that would change the war and give him the victory he thought he had in 1941.

The second problem was there simply were not enough of the new Tiger tanks to guarantee a victory. The T-34 and KV-1 Russian tanks had sloped and thick frontal armor. The 75mm cannon on the Mark IVs had difficulty penetrating it. The 88mm gun on the Panthers and the Tigers cut through the Russian sloped armor and were effective at twice the range of the guns on the Soviet tanks. Hitler counted on his secret weapon tanks to counterbalance the far superior numbers of Soviet armor. But there were far fewer than 100 Tigers ready on May 4, when the plan was agreed to. Optimistically, assuming that the incredibly slow production of the new tanks would accelerate given time, Hitler solved this problem by delaying the attack until July 4.

This delay ignored two realities. To break through and encircle the Russians west of Kursk, the panzers had to fight through the defenses being prepared. The two-month delay benefited both sides, but the Russians more. Waiting for enough Tigers meant allowing two more months of Russian construction on the defenses. The delay also gave the Soviets two more months of tank and assault gun production. According to Jane’s World Armoured Fighting Vehicles , the Soviets were manufacturing almost 2,000 tanks and a few hundred assault guns each month in 1943. This compared with no more than 1,000 a month for the Germans, with only a small percentage of those being the Tiger. So the longer the battle was delayed, the greater the German inferiority in the number of tanks grew. There were also an estimated 44,000 tanks the Americans and British built in 1943. Time was not on the Nazis’ side, but still Hitler ordered a delay of two months. It is no wonder that thinking about the battle for Kursk upset Hitler’s stomach.

Читать дальше