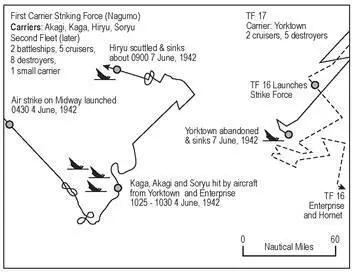

The Japanese invasion plan followed a proven pattern that had been successful many times. The carrier force, the Kido Butai, would lead the attack, neutralizing any land-based airfields and sinking any ships in the atoll. If the first wave of bombers and fighters didn’t do the job, there was plenty of time for a second wave to finish it. This plan assumed that it would take the U.S. Navy at least two days to steam to Midway from Pearl Harbor once they heard about the attack. That would leave plenty of time for Nagumo to thoroughly pummel the atoll before help could arrive. With Midway’s airfield and major defenses bombed into ruin, the battleships would arrive and further bombard the island into submission. By the time the elite assault force landed, resistance would be minor and uncoordinated. By the time the U.S. Navy arrived, the island would be in Japanese hands.

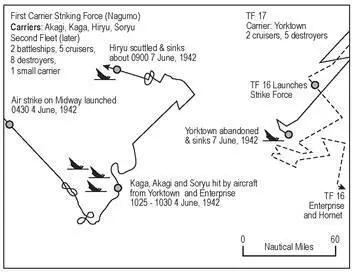

So the first wave of Japanese attack planes went in, but thanks to the broken code they were not able to surprise the island. Every plane at the air base was already in the air when they hit and every weapon was manned and waiting. The air base was damaged, but heavy ground fire prevented the Japanese bombers from completely wrecking the atoll’s defenses. At about the same time the IJN aircraft had brushed past the obsolete U.S. fighters to attack Midway, the heavy bombers, dive bombers, and torpedo planes from Midway had attacked the four carriers of the Kido Butai. While bravely delivered, not a bomb or torpedo struck, and most of the American attackers were shot down.

The need for a carrier aircraft second attack on Midway was one of the contingencies in the fleet commander’s orders. Nagumo prepared to recover the first attack wave’s aircraft and got a second attack ready to bomb the island. Everything was going according to the plan. Then a radio message arrived that changed everything. One of the IJN scout planes had spotted the Yorktown . This was not part of the plan; there weren’t supposed to be any American carriers in the area for days yet. He had been assured just hours before, by a line of scout submarines, that no major ships had been spotted leaving Pearl Harbor. Thanks to Rochefort, the American ships were already gone when the Japanese subs got into place to watch for them.

The Battle of Midway

The information that a U.S. Navy carrier was nearby meant that Chuichi Nagumo was torn between two conflicting orders. One order was to follow the plan and finish off Midway. To do this he had to launch his aircraft at the island again. But he also knew that the intent of the whole plan was to draw out the American carriers, and now one was within attack range. But it was days early, and the IJN battleships were not yet even close. His aircraft would have to take care of the carrier. To go for the Yorktown , Admiral Nagumo had to order the removal of the explosive and shrapnel bombs, which were almost finished being attached to the second wave of aircraft, and the loading of armor-piercing bombs and torpedoes. Only that type of weaponry was capable of damaging an armored carrier and its escorts. But the change would take at least an hour. This was not part of the plan he had been given by Admiral Yamamoto. Nagumo’s orders did not tell him what to do in this situation because the confident Japanese had never considered that the U.S. Navy would not react how and when they expected. And with radio silence, Nagumo could not even radio Yamanoto and ask him what to do.

So Admiral Nagumo, whose strength was carrying out the plans of his brilliant superior, had to take the unusual step of deciding for himself. Did he disobey the orders for the invasion to go for the carrier and risk allowing the Midway air base to be repaired and perhaps new defending aircraft flown in from Hawaii? Or did he ignore the carrier and obey his original orders as written? And here is the mistake that changed the war forever: For a number of minutes, Nagumo did nothing. This hesitation, his inability to decisively disobey an order, even when the situation he was in was unforeseen, changed the entire war in the Pacific.

Doing nothing in war is often a mistake, and in this case the loss of all four carriers and the initiative resulted. If Nagumo had launched the aircraft against the atoll or had gotten them rearmed in time and launched against the Hornet , the war’s history would be very different today.

While only one had been spotted, there were actually three American carriers in range to attack the Kido Butai. So eventually Admiral Nagumo made what was likely the best decision for the new circumstances and ordered a rapid change of the armaments on all of his aircraft to antiship weapons. But the time spent deciding what to do and the chaos of the weapons change meant that not only were the aircraft almost all still on the decks of all four carriers fueled and armed when the American aircraft attacked, but that the land attack bombs, which had been removed, were also still stacked near them. As a result, when the IJN fighters were off chasing the few survivors of two American torpedo groups, aircraft from two groups of U.S. Navy dive bombers were able to hit three of the highly vulnerable Japanese aircraft carriers. The bombs and fuel in the aircraft on the decks of the three ships exploded and greatly increased the damage. Within minutes all three carriers were beyond repair and covered in flames.

Nagumo continued to fight with the remaining carrier, sinking the Yorktown just as his last carrier too was lost. Then his last carrier was sunk, and the entire IJN force had to retreat. The powerful battleship fleet and Admiral Yamamoto never even got close to the island. Midway was saved. Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s hesitation and a lot of luck on the American side meant that the massive IJN superiority in carriers in the Pacific was lost in a matter of hours.

The Stalingrad Disaster

1943

Winter of 1942 had belonged to the Russians. In the snow and freezing weather, they had held the Germans and, in places, had even driven them back. But by spring 1943, a bruised but still unbeaten Nazi army prepared for another series of war-winning attacks. While pressure was kept on Moscow and Leningrad, the real German effort would be in the south.

There were a number of good reasons for the shift. The open steppes and dry plains of southern Russia were more conducive to the Blitzkrieg and massive pincher movements that had served the Wehrmacht well in 1941. The area was much less well fortified and more thinly populated. So southern Russia offered a much better opportunity to break through or capture major elements of the resurrected Soviet armed forces. But perhaps the most compelling reason for the move against southern Russia was that the Reich desperately needed the oil that was on the other side of the Caucasus Mountains.

Two vast attacks were planned. One was to sweep south and grab the oil. The other was to move east and capture the most important city on the Volga River. The Volga was the key route for the Russian north and south transport. It also had to have appealed to Hitler that to control the vital Russian supply line of the Volga River, the city Stalin had named for himself, Stalingrad, had to be occupied.

The original plan to capture Stalingrad was not a mistake. The city was the key to controlling the southern Volga River. It was also one of Russia’s premier weapons manufacturing centers. Perhaps even more than this was the propaganda value of capturing the former Tsaritsyn, named now after the Soviet dictator and Hitler’s greatest nemesis, Stalin. Even the strategic plan started well. Army Group A, under Paul von Kleist, broke through line after line of Russian defenders, crossing Russian defense lines set up on river after river. Army Group B, commanded by Hitler’s favorite general, Friedrich von Paulus, also punched its way through several Russian armies until, by August 23, 1942, the two panzer armies in it had reached the banks of the Volga and were approaching their objective, the city of Stalingrad.

Читать дальше