It’s at this point that a series of mistakes doomed half a million German soldiers and changed the momentum of World War II irrevocably. All of these mistakes were made worse by Hitler’s choice of commander for the Sixth Panzer Army, von Paulus. The general had been chosen not because of his battlefield experience but because he got along with the testy Adolf Hitler. And in Nazi Germany that qualified you for anything, even command of one of the few elite panzer armies. In 1941, Friedrich von Paulus had shown himself to be an excellent administrator and planner. He was the chief architect of Operation Barbarossa and was known for his skill at staff work. The problem was that von Paulus as a field commander… well, he was a very good staff officer. He did a competent but unimaginative job and obeyed orders, Hitler’s orders, to the letter.

As Army Group B approached Stalingrad, Hitler personally ordered half of its armored strength, Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army, to hurry south and join up with Army Group A. It was to assist in the final lunge for the Caucasian oil fields. The decision was a mistake that cost both army groups the use of that armored formation for weeks while it changed direction and moved south. Still, even with his Sixth Panzer Army alone, von Paulus began to successfully attack Stalingrad.

The city of Stalingrad in 1942 had grown in a long strip along the Volga River, ten miles long and from a few to five or six miles deep. Most of the large buildings and factories were located near the river. Even at half strength, the power of a panzer division was great, and soon the Sixth Panzer was grinding into the city from north, west, and south. To the east was the Volga River, and herein was a continuing mistake the unimaginative von Paulus made. He never attempted to cross the Volga, and so he was never able to completely surround or cut off Stalingrad.

The Volga was able to act as the route for reinforcement and supply throughout the battle for the city. By never even attempting to cross the Volga, the Germans provided the city’s defenders with a safe base from which hundreds of thousands of reinforcements were shuttled into the city. The east bank also provided a safe location for masses of artillery, which later constantly punished the Germans. Such an attack certainly was possible, especially early in the battle for the city, and was a much better use of the highly mobile armored units in a panzer army than was house-to-house urban warfare. So von Paulus failed to surround a city he was attacking and left the enemy a secure and unmolested base just a few hundred very wet yards away from it.

From September on, the Germans drove the Russian defenders back against the Volga. By December, the defenders no longer could maintain a continuous line. Only pockets of fierce resistance remained. But those pockets were constantly reinforced. In one such pocket was the now-famous Dzerzhinsky Tractor Factory. The plant had been converted to manufacturing T34 tanks and continued in production even when completed tanks, often showing mostly unpainted metal, would roll off the line, be armed, manned, and find themselves in combat as they pulled out of the factory’s doors.

Often the Germans would occupy a part of the city after hand-to-hand fighting during the day and then would have to pull back to their bases for supply. The Russians would reoccupy the ruined buildings that night. The next day, the Nazis would have to retake the same building again. Russian soldiers, many ill trained, were poured into Stalingrad by the tens of thousands and died in equally great numbers. The sewers under the city also became the scene of a surreal parallel battle where the dead and wounded simply disappeared into the muck. By the time cold weather arrived, the Sixth Army controlled nine-tenths of the city. Their own casualties had been high, but the Russians’ casualty numbers were much higher. It was von Paulus’ stated hope that he was punishing the Russian Sixty-second Army so badly they soon would have to give up the city. He was wrong. On November 8, Luftflotte 4, a good portion of the Sixth Army’s bombers, had to be withdrawn. They were needed in North Africa. Just as the Russians had been forced into a strip less than a thousand yards deep, the German pressure began to ease.

The Battle for Stalingrad

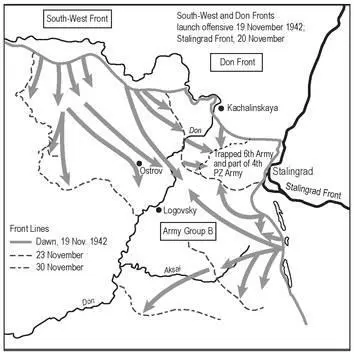

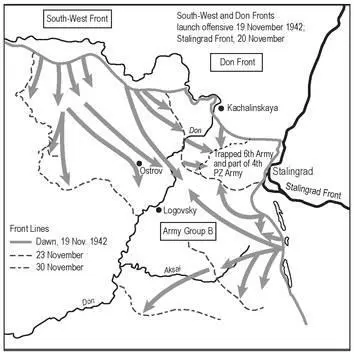

On November 19, everything changed. For months Marshal Zhukov had been accumulating fresh Russian armies and just waiting until winter and enough troops arrived. Now he had both. The Battle of Stalingrad itself had taken the efforts of the entire Sixth Panzer Army. With the Fourth Panzer Army gone, von Paulus had to use whatever else he had at hand to defend the flanks of the salient that ended in Stalingrad. The flanks north and south of the city were held only by thinly spread Romanian divisions and backed up by virtually nothing. These underequipped and often reluctant Romanians could see and hear the buildup as two tank armies and eighteen infantry divisions prepared to attack in just the north. They begged for reinforcements, but von Paulus had no one to send and was focused on completing his conquest of the city. At sunrise on the nineteenth, Russian Operation Uranus began when overwhelming numbers of Soviet tanks and infantry easily shattered the Romanian divisions north of Stalingrad. Two days later in the south, the Romanian IV Corps received the same treatment. The Romanians who were not killed or captured were forced into Stalingrad. Within days, both attacking Soviet armies had met and closed the trap. This time it was the Germans who were encircled. More than a quarter of a million men in the Sixth Panzer Army and allied formations were trapped in Stalingrad.

The German high command wanted to order an immediate breakout. But a month earlier Hitler had told a crowd of thousands in the Berlin Sports Palace that the German army would never withdraw from Stalingrad. He would not take back his promise. He instead met with Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe. Goering promised that his flyers would be able to deliver 750 tons of supplies per day into the city. Unfortunately, the reality was far different. To haul 750 tons, the Luftwaffe needed every transport and most of the bombers on the eastern front to fly four supply missions each day. The trouble was there was not enough daylight for four missions, or often even two. Nor was there ever enough aircraft available. The most tonnage that was ever actually flown into the trapped army, in one day, was 289 tons on December 19. The average, though, was only ninety-four tons per day, or an eighth of the amount needed. Each day, the trapped soldiers had less ammunition and less to eat. By the end of the airlift, in January 1943, the Luftwaffe had lost almost 500 aircraft. One out of every two planes had been shot down or crashed trying to fulfill Goering’s promise. But Hitler himself ensured that the pilots’ efforts were all in vain.

After they had joined up, the Russian armies formed a defensive position facing both Stalingrad and the Germans outside to the west. They formed lines of circumvallation, whose design would have looked familiar to Caesar’s legionnaires at Alesia. Unfortunately for the trapped Sixth Army and von Paulus, this worked just as well for Zhukov as it had for Caesar. Arguably the best commander the Germans had was sent to deal with the problem of saving the Sixth Panzer Army. This was Erich von Manstein. He mounted a counterattack using Hoth’s Fourth Panzer. It penetrated to within thirty-four miles of Stalingrad against determined Russian opposition. Again, the German high command asked for permission for the Sixth Panzer Army to break out and join up. Again, Hitler refused, and von Paulus, knowing that this decision likely doomed his army, obeyed. Facing overwhelming numbers of Russian tanks, Hoth eventually had to withdraw. A few weeks later, the Soviets launched an offensive named Winter Storm. This attack almost trapped all of Army Group South and forced a general withdrawal of more than 100 miles. The Sixth Army in Stalingrad was now separated by almost 150 miles from the new German defensive line.

Читать дальше