The astonishing thing is that a Nazi court dared to pass so severe a verdict on the Nazi hymn. The judges, however, were careful not to refer to Horst Wessel as a plagiarist, but to some vague “singer of the Horst Wessel song.” Nevertheless, they went on to say: “Above all, an artist with a strong musical sense will feel himself bound to conform to the words far more than did the author of the song Up with the Flag. The very beginning shows a definite discrepancy of word and tune; the line ‘Up with the flag’ would seem to indicate a movement upwards, whereas the melody goes downward, without any apparent necessity for this. A further disagreement between words and melody is to be found in the line, Kameraden die Rot Front und Reaktion erschossen, for the text, contrary to the meaning, emphasizes die with a higher note, which, quite gratuitously, is also louder than the rest of the text.”

The hero and martyr of Hitler’s regime died as a notorious pimp; the “National Hymn,” his life work, is not only a plagiarism, but a clumsy one.

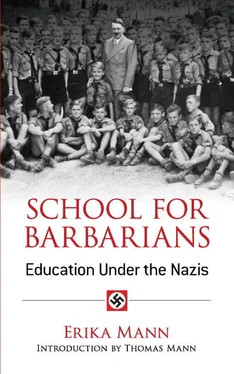

However, Nazi school children know Horst Wessel as a heroic, saintly figure of light, a godlike hero hated by the enemies of the Nazis, a man who sacrificed his life in the battle against evil. His song, they are told — and they have not so much as a suspicion that the accuracy of what they are taught is doubtful — is one of the greatest creations of the German spirit. And they sing it lustily.

“Occidental mathematics,” writes one Dr. Erwin Geek, in The National Socialist Essence of Education, “as it has developed in the past three hundred years, is Aryan spiritual property; it is an expression of the Nordic fighting spirit, of Nordic struggle for the supremacy of the world beyond its boundaries.”

It sounds like a vast joke against learning — “an expression of the Nordic fighting spirit!” But we have been warned. At least, now, the problems in arithmetic cannot surprise us.

They all have to do with airplanes, bombs, cannon, and guns.

The booklets called Völkisches Rechnen — a new term meaning “people’s arithmetic” or “national-political problems of arithmetic” — account for this puzzling adjustment: sums in terms of bullet trajectories! Unfortunately, there is not much that can be done about national political problems with ordinary addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division as they are usually taught in the public schools. In the secondary schools, more can be done. National Political Practice in Arithmetic Lessons sets the following problems:

I. Germany had, according to the Versailles Treaty, to surrender all her colonies. (An enumeration of colonies and mandates, with estimates of population and area is given)

A. What was Germany’s total loss in population and territory?

B. How much did each mandatory power receive in territory and population?

C. How many times greater is the surrendered territory than the area of Germany?

D. Compare the population of Germany with the population of the lost territories.

II. A bombing plane can be loaded with one explosive bomb of 35 kilograms, three bombs of 100 kilograms, four gas bombs of 150 kilograms, and 200 incendiary bombs of one kilogram.

A. What is the load capacity?

B. What is the percentage of each type of bomb?

C. How many incendiary bombs of 0.5 kilograms could be added if the load capacity were increased 50%?

III. An airplane flies at the rate of 240 kilometers per hour to a place at a distance of 210 kilometers in order to drop bombs. When may it be expected to return if the dropping of bombs takes 7.5 minutes?

Another textbook, National Political Application of Algebra, by Otto Zoll, achieves the same ends as the Practice. “How many people can seek protection in a bomb-proof cellar, length 5 meters, width 4 meters, and height 2.25 meters? Each person needs 1 cubic meter per hour, and they remain there for three hours.”

In his little book, Aerial Defense in Numbers, Fritz Tegeder asks the same kind of question: “If the speed of an airplane is 175 kilometers per hour, how many hours does it take for a plane to reach Moscow, 1,925 kilometers from Berlin; Copenhagen, 481 kilometers from Berlin; and Warsaw, 817 kilometers from Berlin?” In this problem the 7.5 minutes which, as everyone knows, a “passenger plane” needs to drop its bombs, are not mentioned.

Another book, Germany’s Fall and Rise — Illustrations Taken from Arithmetic Instruction in Higher Grades of Elementary School, which in 1936 had reached a circulation of 715,000 copies, asks: “The Jews are aliens in Germany — In 1933 there were 66,060,000 inhabitants in the German Reich, of whom 499,682 were Jews. What is the percentage of aliens?”

And this is only the surface. What is to be said of such pamphlets as Mathematical Problems of Physical Training, and Knowledge of Military Science? Or Mathematical Problems for Grammar School and the Collection of Artillery Problems for Use in the Upper Classes of Advanced Schools?

Before we talk about the teaching of German, let us note that the Führer and Reich Chancellor, the master and educator of the German people, is hardly a master of the language. There is not a page of Mein Kampf whose errors do not hit you in the eye. Every speech of Hitler’s is crowded with grammatical mistakes; it is beyond his power to speak a few consecutive German sentences correctly.

The answer might be that he is no scholar, but a “man of the people,” as he has reiterated. But he is the people’s ruler. And his speeches are not faulty because of extreme simplicity, but because of their ambitious rhetoric, his attempts at a literary German. The Führer’s language is an indictment of his intelligence, and one to which the attention of foreigners must be called before they can fully appreciate it. Actions may be judged according to time and place, and their values may change; but style, language (apart from content) are crystallized at the moment. Hitler’s use of language is the worst imaginable, and it will remain at that level. Its danger is that, spoken by him, these utterances are for the German people — his wish is theirs, his opinion theirs, and his use of language must be their language. Those who care for the German language may be anxious for its future when they see its deterioration during the five years of Hitler’s rule; newspapers, magazines, schoolbooks — the entire official literature — have fallen into the florid yet brutal, military and vulgar forms of expression that are typical of the Führer himself.

The teaching of German, like all lessons, is not an end in itself, but teaches children how to express the thoughts of the Führer in his own language — and nothing else. A small grammar by Richard Alschner, published recently in Leipzig under the sonorous title of Sprachkundliche Kleinarbeit im Neuen Geiste (which means something like A Study of Language in the New Spirit ), says in the preface:

“Whatever moves the soul of a people, in joy and sorrow, in meditation and battle, in creation and festivity, vibrates in unison with the entire curriculum, and by no means least in the teaching of language. Here, too, it is a matter of coinciding with life itself! Proximity to the present! Relation to the people! For that reason let us also give utterance to the mighty events of the time in our lessons in German! That which fills the heart of the people is spilled by the tongue of youth! The stream of strong blood-folk thought, feeling, and will must be permitted to flow, warm with life, into the form of the word. The result will be a teaching of folk-culture in the mother tongue, and to make this live and be watchful in the growing generation, so that this may, with its own treasure of words belonging to our day and age, express the new treasure of thought, gather it into itself, and let it root ever deeper in the German essence ( Wesensart ), growing ever more deeply rooted, growing ever more into the German mode of thought, the German mode of living, and the German view of the world ( Weltschau ).”

Читать дальше