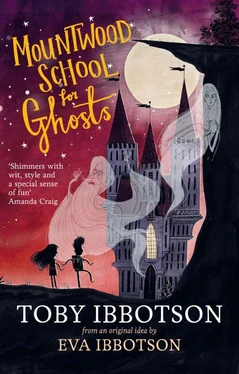

Mountwood School for Ghosts

by

Toby Ibbotson

One

The Trouble with Ghosts

Most people know what a hag is. They used to be common enough in every parish in the land. Any old lady who lived alone in a cave by the sea or a tumbledown cottage in marshland or forest might be a hag. If she had a wrinkly face, bushy eyebrows, a gobber tooth, a squint eye, a squawky voice, a scolding tongue and a cat, then she probably was a hag. And if she had hair growing on the inside of her mouth, then there was no doubt about it.

But there are also Great Hagges. They are spelled differently because they are quite rare. You won’t find a Great Hagge living in a half-ruined bothy on a wuthering heath. You are more likely to find one living in a pleasant ground-floor flat in north Oxford. On the outside they are less fierce and disgusting than common hags; they are less hairy, and much bigger. But, inside, a Great Hagge is far more interesting and dangerous and full of ideas.

An ordinary village hag goes out at night to sit on people whom she doesn’t like and stop them breathing, so that they wake in a panic. That’s why some people look hag-ridden when they come down to breakfast. Great Hagges cannot be bothered with stuff like that. They dress properly (they like tweed), they make plans. They organize and put things right. They can’t help it; that’s the way they are. But putting things right is not the same as being nice. Great Hagges aren’t nice. They aren’t do-gooders. Nothing like that. None of your knitting scarves for tramps or founding homes for stray kittens. They don’t like people (not live ones, anyway; they enjoy a nibble of human flesh if it’s properly cooked) — but they don’t not like them either. It’s just that for a Great Hagge it is quite impossible to ignore a mess, and most human beings are in a mess. People have feelings that get them into trouble. They feel sorry for other people who are ill or sad, they fall in love and out of love with each other, they worry about doing the right thing.

But of course the biggest and most stupid messes are made by politicians and heads of schools and people with more money than sense. Their messes mess up everybody else, and those are the kind that Great Hagges simply cannot abide.

So, if you meet a large fierce lady with a loud voice, who is bossier than the bossiest person you have ever met; a member of a parliamentary committee, or headmistress of a school for rich girls, or chairwoman of a hospital trust — she just might be a Great Hagge. But then again she might not be. After all, lots of important bossy ladies who are ordinary human beings have one long eyebrow and knobbly knees and huge feet. You would have to get up close to be sure. If you ever saw a Great Hagge in a swimsuit you would know instantly what she was. But that is not very likely to happen.

One Wednesday afternoon about a hundred years ago three Great Hagges met for tea; they were old friends, and they liked to stay in contact and exchange news. Their real names were Fredegonda, Goneril and Drusilla, though those were not the names by which they were known. Fredegonda was chairwoman of the board of a high-security prison for serious offenders; she was tall and bony, with big front teeth, and had to have her shoes specially made because her feet were on the large side even for a Great Hagge. She also had a special thumb. It ran in the family, because she was descended on her mother’s side from the great Irish hero Finn McCool. She had never been known to lose her temper, but when she told some wicked murderer in her icy voice that he should ‘get a grip’ or ‘pull his socks up’, then he almost always became as gentle as a lamb.

Goneril was principal of a college of nursing. She was not as tall as Fredegonda, but she was a lot wider and very strong and solid, and possessed a rather particular eye, the left one. Her nickname among the student nurses in her charge was the ‘Wardrobe’, but none of them ever used it within miles of her, because she did lose her temper sometimes, and the results were horrifying — things happened that were hard to explain.

The reason for this, of course, was that all Great Hagges can curse and spellbind if they wish to, and when they lose their temper, then they do sometimes wish to.

The third Great Hagge, Drusilla, was a Lifetime President of the Society for the Preservation of the British Heritage. She cared very deeply about the woods and rivers and hills and old houses of Britain. Drusilla had frizzy hair, a twinkly eye and a rosebud mouth, and her head was as round as the full moon. But anybody who thought she was a softy was in for a nasty surprise. She was more practical and artistic than the other two, and she could be quite un-Haggeish sometimes. She had smoked a cigarette once, and on another occasion danced a tango at a New Year’s Eve party with a gentleman from South America, a flower between her teeth. Luckily he was quite short, so her nose was well above his head and he was in no serious danger of being skewered in the eye. For her nose was no ordinary nose.

The three friends had worked very hard all their lives (Hagges have very long lives), sorting out various messes, and educating, and putting things right, and on this particular Wednesday, in the drawing room of Goneril’s Bloomsbury flat, they made a momentous decision.

‘My dears,’ said Fredegonda, sipping her tea, ‘I think the time has come. Enough is enough.’

The other two nodded. Great Hagges are tough, but even a Great Hagge gets tired eventually. It is absolutely exhausting telling other people what to do all day; any teacher will tell you that. So that afternoon the three friends decided that it was time to retire at last. They would return to nature and spend their last remaining years in peace, enjoying simple pleasures. Drusilla knew of a comfortable cave in the far north-west of Britain. She had spent her summer holidays there as a schoolgirl.

A few days later all three of them resigned from their important jobs and moved.

Their cave lay on the very shore of the great western ocean. At low tide, a crescent of silver-white sand stretched before the mouth of the cave. When the tide was high the beetling black cliffs of the headland plunged sheer into the surf, the cries of terns and skuas pierced the breakers’ roar and seawater swirled soothingly around the ankles of the three companions as they sat enjoying their afternoon tea in the living room; Great Hagges do love to keep their feet damp. It was like living in paradise. They went for walks on the beach, gathering cockles and exploring rock pools. Drusilla found a sea slug and kept him as pet. She called him Mr Perkins, because he looked like the owner of a railway company with whom she had once had to be very firm; so firm, in fact, that he didn’t survive the experience.

‘We gave him such a moving send-off,’ she said to her companions. ‘I arranged the floral tributes myself.’

They got to know some of the locals. A couple of kelpies lived nearby, and the Mar-Tarbh, Dread Creature of the Sea, came over sometimes from Iona to say hello and exchange gossip.

For many years, ninety-seven to be precise, they lived their quiet life, while the world outside moved on. The three Great Hagges of the North became a rumour, a mere memory preserved among the ghosts, ghouls, sprites and other inhabitants of invisible Britain.

As far as the crofters and fishermen of the island were concerned, the Great Hagges kept themselves to themselves. But of course they met them sometimes, and said ‘good morning’ or ‘nice weather today’. The people of the Western Isles are not the prying kind, and they are lot cannier about what goes on in the other world than most of us. They might have sat by their peat fires of an evening and wondered a bit about the large strange ladies who had taken up residence among them, but they knew better than to poke their noses into what didn’t concern them.

Читать дальше