Goneril said nothing. Her eyes were fixed firmly on the road ahead. She was still upset. But she was also a bit ashamed of herself. She had always respected the authorities, and if they had been stopped by a policewoman, and not a policeman, then things might have turned out very differently. One of the very few things that had pleased the Hagges about the modern world was the advancement of women. The first time they saw a lady police officer they had been very excited.

‘That I should live to see the day!’ Drusilla had exclaimed. At one time she had fought hard for the rights of women.

But now there was nothing for it. They left the main road at the next turning and started to make their way by the shortest possible route back to the Scottish border. In the pale light of dawn they saw drystone walls marching over sweeping moorland pastures, and heard the cry of the curlew. Stone byres and cottages huddled in the valleys out of the wind. They were in the borderlands.

They came to yet another fork in the narrow winding road.

‘Left or right?’ asked Goneril, bringing the car to a halt.

Fredegonda, sitting with the map on her knees in the front passenger seat, was silent. She was lost. She hated to admit it. She had always prided herself on her map-reading skills, but the ancient map and the maze of country lanes had defeated her. To make things worse, the morning mist still lay on the hills and it was impossible to get her bearings.

Drusilla sat up in the back seat and sniffed. ‘Let’s go left. I like the smell of it.’

Soon they were driving through the Debatable Lands, a part of the country that for hundreds of years was neither England or Scotland, but a lawless tract where outlaws and bandits and fierce clan leaders held sway, stealing sheep, feuding and pillaging, both to the north and to the south, and then retreating by secret pathways over the moors to their fortified peel towers.

Drusilla had taken over the navigation, and now they followed her nose, which she stuck out of the window. Something in the air was drawing her on, something that whispered to her of damp leaf mould, rotting flesh, mouse droppings, decomposition and decay. It was irresistible to Drusilla, reminding her of happy afternoons in the kitchen trying out new recipes.

Suddenly she cried, ‘Here, turn right here!’ and Goneril swung the car into a narrow lane that dived steeply downhill through a dense stand of fir trees.

They were descending into a narrow valley. On both sides dark crags were outlined against the sky, cutting out the light. The further in they drove, the gloomier it became. Just as Goneril was beginning to think that the track was turning into a path, and was starting to worry about her shock-absorbers, the valley opened out slightly, and before them, crouched darkly under an overhanging face of blackened rock, was a castle.

It wasn’t a big castle, more a large rambling house, but it had battlements and slit windows. The ancient sandstone walls, gnawed by wind and rain, were adorned with waterlogged moss and slimy lichens.

The Great Hagges got out of the car and stood for a moment drawing the damp and foetid air deep into their lungs.

‘Oh, how delightful,’ said Fredegonda. ‘Just imagine if…’ She didn’t have to finish her sentence. They were all thinking the same thing, and as one they approached the castle.

The ground around the building was squelchy — any drainpipes and gutters that had ever existed were long gone — and all three Hagges just longed to remove their sensible shoes and woollen stockings and feel ooze between their toes. But they didn’t. Business must come before pleasure.

The front entrance had a big door of solid, iron-studded oak. It had been made to resist the attacks of bloodthirsty marauders from both sides of the border and was still in good shape. Beside it hung a bell pull on an iron chain. Goneril gave it a tug, and it came off in her hand.

‘Oh dear,’ she said.

‘The place looks deserted,’ said Drusilla. ‘Shall we just have a peep inside?’

Goneril put the flat of her hand against the door and gave a little push. With a wrenching sound the two iron bars on the inside bent like rubber and sprang loose, and the door creaked inwards on its hinges.

Drusilla giggled. ‘It seems to be open.’

The lower floor was a single stone-flagged vault, where livestock and women had been herded together for protection in troubled times. Cobwebs curtained the tiny windows set high in the walls, and a large rat scuttled along by the wall.

‘This is very promising,’ said Fredegonda, ‘but we must not get our hopes up yet.’

On the floor was a big flat block of sandstone, with a ringbolt set into it. A chain had once been attached to the ringbolt, and two strong men, with the help of a wheel and ratchet, could lift the stone and expose the mouth of a well, which was the only source of water during a siege. Now Goneril walked forward and pushed the stone aside with the outside of her foot. She leaned over the dark well-mouth.

‘Cooee, is there anyone at home?’

At first there was no answer. The only sound was a slow drip, drip, dripping. Then a pale bluish mist began to gather slowly on the black surface of the water at the bottom of the well. It swirled gently for a while, and finally became a face, hollowed-eyed, with straggly hair and a half-open gap-toothed mouth.

It was the ghost of Angus Crawe, who had a great many dark deeds on his conscience, or would have had if he had a conscience. One evening he had got into a fight with his nephew over a young woman whom they had captured in a raid on Alnwick. He managed to slaughter his nephew, but slipped on the blood that splattered the floor and fell headlong into the well. His nephew’s mates had quite simply put the cover-stone back and gone out to a party.

‘Oh, there you are,’ said Goneril. ‘We are looking for the laird. Can you help us?’

The pale mouth moved, trying to form words, but Angus Crawe had not spoken for centuries, and his broad Northumbrian accent had not been easy to understand even when he was alive.

‘Could you speak up, please? And try to articulate.’

‘Eee… Eees… Eeble.’ said Angus.

‘What on earth are you saying, man?’ Goneril was getting irritated. ‘Eels? Eagles? Evil?’

Finally Angus produced a proper word. ‘Peebles,’ he said.

Goneril was very determined, and after a long question-and-answer session they worked out what they needed to know. The last laird of the castle came from a long line of uncouth border reivers and was no better than his wild ancestors. He had married a girl from the local town, who had soon discovered what a terrible mistake she had made, and being a resourceful lass she had doctored the brakes of his Land Rover. The very next day he tried to slow down as usual to take a bend at the bottom of a steep hill, but the Land Rover just flew straight on and landed in the riverbed far below. The vehicle was totally demolished, and so was the laird. His wife inherited all his wealth, which was considerable, and left the hated home of her husband to rot. She was now enjoying a very expensive holiday at the Peebles Hydro, a holiday that had already lasted for several years.

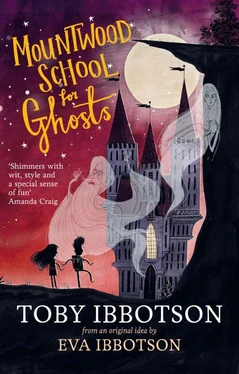

The Hagges had found what they were looking for. Within a few days they had contacted the Peebles Hydro and been told in no uncertain terms that they were welcome to the dratted place and much good may it do them. The price was very reasonable. At first there were some delays caused by lawyers in Edinburgh who didn’t seem to understand that there was no time to waste. But the Hagges paid them a visit, and after that everything went very quickly indeed. They moved in and were soon hard at work planning a curriculum and drafting important documents. The name of the castle was Mountwood, and within a surprisingly short period of time they were ready to open the doors and welcome the first students.

Читать дальше