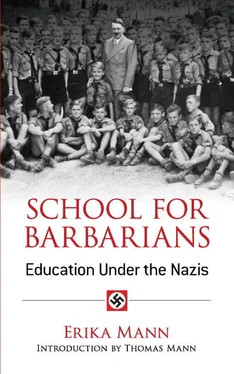

Erika Mann

SCHOOL FOR BARBARIANS

Education Under the Nazis

INTRODUCTION BY THOMAS MANN

“Whoever has the youth has the future,” said the cunning master of Germany many years ago, when he was still an obscure Austrian ex-corporal. This book damningly shows how far he has gone toward warping pliable young minds into the monstrous Nazi pattern. Here is a saddening record of infamy that has never been told before and that bodes ill for generations to come: family life poisoned and destroyed; a once proud school system debased; babes in arms pressed into a sinister system of regimentation that allows no child to draw a breath save by leave of The State.

We see a mother sigh in relief because the sun does not shine — today her child will not ask to play outside with his fellows, a joy enjoined from on high because his father was Jewish. We see hooliganism glorified, disreputable characters proclaimed as heroes. We see even arithmetic and drawing freighted with a hateful cargo of death. We see frail young frames crushed beneath the burden of heavy packs on forced marches. We see vile anatomy demonstrations with haunted Jewish children as models.

As incident piles on ghastly incident — substantiated for the most part by official documents — the reader loses any remaining feeling of security engendered by the broad reaches of the Atlantic, any wishful thinking about the passing character of Nazism. Here is a blueprint of barbarism being reared to endure. And somehow the crazy structure stands — for there is no restraint, no effective opposition.

Miss Erika Mann is peculiarly qualified to draw this picture of anguish with bold and unsparing strokes. Herself a member of the war generation of German youth, she knows at first hand the life of young people under the Empire, the Republic, and now the Third Reich. The daughter of the famous Nobel Prize winner, Thomas Mann, author of The Magic Mountain and the Joseph series, Erika Mann has accomplished what few children of famous parents achieve. She has become a distinctive, creative personality entirely in her own right. She went on the stage when very young, became a pupil of Max Reinhardt, and scored a resounding success with her political cabaret, Peppermill, which she wrote and directed herself, and which ran for more than a thousand performances in six countries. Since coming to the United States, she has lectured widely on Nazi Germany. The most heartening note in her new book is her faith in American democracy and the most touching section deals with the almost magic effect which residence in a free country exercises on two little refugee boys. It works both ways — this “Who has the youth has the future.”

THROUGHOUT MY WHOLE long journey from East to West and back again across the vast continental stretches, the author of this book, my dear daughter Erika, was beside me; her faithful help enabled me to meet the demands of an enterprise, fruitful and gratifying indeed, yet at the same time not always easy. How often did she not act as interpreter between me and the public; both with the press, and when, after a lecture, I was questioned by the audience! I would answer in German, English being still rather hard for me; and she would skillfully translate — skillfully, and as I think very much to the advantage of my replies; since there was added to their content the charm of a sweeter voice and the animation of a gifted and intellectual feminine personality.

Accordingly my pleasure is great in being able to act the interpreter in turn between her and the American public; and to introduce her book to readers who are interested in the political and moral problems of the day. It has a repellent subject, this book: It tells, out of a fullness of knowledge, of education in Nazi Germany and of what National Socialism understands by this word. Yet strangely enough, the book is the opposite of repellent. For even its pain and anger are appealing; while the author’s sense of humor, her power of seeing “the funny side,” the gentle mockery in which she clothes her scorn, go far to make our horror dissolve in mirth. It enfolds the unlovely facts in a grace of style and a critical lucidity; and most consolingly opposes to the shocking and negative qualities of malice and falsity the positive and righteous force of reason and human goodness.

The fundamental theme of the book, education in Germany, proves to be an extraordinarily fruitful point of departure for an exposition of the whole National Socialist point of view. That it should be a woman who has chosen it is not strange, but it is surprising to see what a comprehensive and fully informed portrayal of the totalitarian state results from this deliberate limitation to a single theme. The picture is so complete that a foreigner wishing to penetrate into that uncanny world might say that he knows it after he has read this book. All the grim concentration of the present German leaders on the single thought of the power of the State; all their desperate determination to subordinate to that idea the whole intellectual and spiritual life of the nation, without one single human reservation—all of it comes out with startling clarity in this description and analysis, accompanied by a wealth of only too convincing detail of the National Socialist educational program.

I say program because it is of the future. It is an inexorable first draft of what the German of the future is to be. Nothing escapes it. With iron consistency and relentlessness, fanatically, deliberately, meticulously, the Nazis have gone about putting this one single idea into practice and applying it to each and every department and phase of education. The result is that education is never for its own sake; its content is never confined to training, culture, knowledge, the furtherance of human advancement through instruction. Instead it has sole reference, often enough with implication of violence, to the fixed idea of national preeminence and warlike preparedness-.

The issue is clear! It is a radical renunciation—ascetic in the worst sense of the word — of the claims of mind and spirit; and in these words I include the conceptions truth, knowledge, justice — in short all the highest and purest endeavors of which humanity is capable. Once, in times now forgotten, we knew a definition: “to be German, means to do a thing for its own sake.” The words have lost all meaning. German youth is to devote itself to nothing for its own sake; for everything is politically conditioned, everything shaped and circumscribed to a political end. The sense of objective truth is done to death; it is referred to something outside of itself, to a purpose which must be a German purpose — the purpose of the State to have absolute power over the minds of men within its borders, and to extend its power beyond them.

Such an arbitrary purpose, such a permeation of all truth and all research with political aims, makes us shudder; and the shudder is even more physical than it is moral. The program is so violent, so unhealthy, so convulsive that it thereby betrays how ill-adapted it is to the nature of the people upon whom it is inflicted — or rather, who believe that they must inflict it upon themselves. The glory of the German nation has always lain in a freedom which is the opposite of patriotic narrow-mindedness, and in a special and objective relation to mind. Germany gave birth to the phrase: “Patriotism corrupts history.” It was Goethe who said that. The true and extra-political nature of this people, its true vocation to mind and spirit, become clear today in the very immoderation, the “thoroughness” with which it abjures its best, its classic characteristics, offering them up on the altar of totalitarian politics at the behest of leaders who do not feel the sacrifice. This people of the “middle” is in actual fact a people of extremes. Shall we have power, shall we be political? Then away with spirit, away with truth and justice, independent knowledge and culture! Heroically it throws its humanity overboard, to put itself in alignment for world-mastery.

Читать дальше