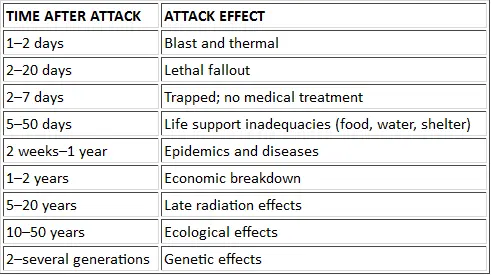

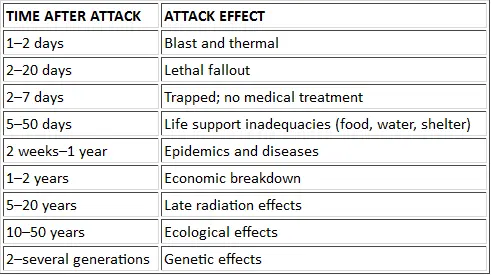

A government report later outlined the “obstacle course to recovery” that victims of such nuclear attacks would have to navigate:

Although the human toll would be grim, the authors of the report were optimistic about the impact of nuclear detonations on the environment. “No weight of nuclear attack which is at all probable could induce gross changes in the balance of nature that approach in type or degree the ones that human civilization has already inflicted on the environment,” it said. “These include cutting most of the original forests, tilling the prairies, irrigating the deserts, damming and polluting the streams, eliminating certain species and introducing others, overgrazing hillsides, flooding valleys, and even preventing forest fires.” The implication was that nature might find nuclear warfare a relief.

Kissinger had once thought that Western Europe could be defended with tactical nuclear weapons, confining the damage to military targets and avoiding civilian casualties. But that idea now seemed inconceivable, and the refusal of America’s NATO allies to build up their conventional forces ensured that a military conflict with the Soviet Union would quickly escalate beyond control. During a meeting in the White House Situation Room, Kissinger complained that NATO nuclear policy “insists on our destruction before the Europeans will agree to defend themselves.”

Nixon’s administration soon found itself in much the same position as Kennedy’s, urgently seeking alternatives to an all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union. “I must not be — and my successors must not be — limited to the indiscriminate mass destruction of enemy civilians as the sole possible response,” President Nixon told Congress. Phrases like “flexible response” and “graduated escalation” and “pauses for negotiation” seemed relevant once again, as Kissinger asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop plans for limited nuclear war. But the Joint Chiefs still balked at making changes to the SIOP — and resisted any civilian involvement in target selection. The debacle in Vietnam had strengthened their belief that once the United States entered a war, the military should determine how to fight it. When Kissinger visited the headquarters of the Strategic Air Command to discuss nuclear war plans, General Bruce K. Holloway, the head of SAC, deliberately hid “certain aspects of the SIOP” from him. The details about specific targets were considered too important and too secret for Kissinger to know.

The Pentagon’s reluctance to allow civilian control of the SIOP was prompted mainly by operational concerns. A limited attack on the Soviet Union might impede the full execution of the SIOP — and provoke an immediate, all-out retaliation by the Soviets. A desire to fight humanely could bring annihilation and defeat. More important, the United States still didn’t have the technological or administrative means to wage a limited nuclear war. A 1968 report by the Weapons Systems Evaluation Group said that within five to six minutes of launching a submarine-based missile, the Soviet Union could “with a high degree of confidence” kill the president of the United States, the vice president, and the next fourteen successors to the Oval Office. The World Wide Military Command and Control System had grown to encompass eight warning systems, sixty communications networks, one hundred command centers, and 70,000 personnel. But the ground stations for its early-warning satellites could easily be destroyed by conventional weapons or sabotage, eliminating the ability to detect Soviet missile launches.

The National Emergency Airborne Command Post — a converted Boeing 747, designed to take off, whisk the president away from Washington safely, and permit the management of nuclear warfare in real time — did not have a computer. The officers manning the plane would have to record information about a Soviet attack by hand. And the entire command-and-control system could be shut down by the electromagnetic pulse and the transient radiation effects of a nuclear detonation above the United States. Communications might be impossible for days after a Soviet attack.

The system had already proven unreliable in conditions far less demanding than a nuclear war. In 1967, during the Six Day War, urgent messages warning the USS Liberty to remain at least one hundred miles off the coast of Israel were mistakenly routed to American bases in the Philippines, Morocco, and Maryland. The spy ship was attacked by Israeli planes almost two days after the first urgent warning was sent — and never received. The following year, when the USS Pueblo was attacked by North Korean forces, its emergency message calling for help took more than two hours to pass through the WWMCCS bureaucracy and reach the Pentagon. The American naval commander in Japan who managed to contact the Pueblo couldn’t establish direct communications with the Pentagon, the Situation Room at the White House, or commanders in the Pacific whose aircraft might have defended the ship.

During a conflict with the Soviet Union, messages would have to be accurately relayed within moments of an attack. A decade after the Kennedy administration recognized the problem, despite the many billions of dollars that had been spent to fix it, the command-and-control system of the United States was still incapable of managing a nuclear war. “A more accurate appraisal,” a top secret WSEG study concluded in 1971, “would seem to be that our warning assessment, attack assessment, and damage assessment capabilities are so limited that the President may well have to make SIOP execution decisions virtually in the blind, at least so far as real time information is concerned.” A few years later another top secret report said that the American response to a nuclear attack would be imperfect, poorly coordinated, and largely uncontrolled, with “confused and frightened men making decisions where their authority to do so was questionable and the consequences staggeringly large.”

• • •

AS THE SOVIET UNION ADDED multiple warheads to its ballistic missiles, Pentagon officials began to worry about the vulnerability of America’s nuclear forces. A Soviet surprise attack might wipe out not only the nation’s command-and-control facilities but also its land-based missiles. To deter such an attack, the Strategic Air Command considered a new retaliatory option, known as “launch on warning” or “launch under attack.” As soon as a Soviet attack was detected — and before a single warhead detonated — the United States would launch its land-based missiles, saving them from destruction. A launch-on-warning policy might dissuade the Kremlin from attempting a surprise attack. But it would also place enormous demands on America’s command-and-control system.

Missiles launched from Soviet submarines could hit Minuteman and Titan II bases in the central United States within about fifteen minutes; missiles launched from the Soviet Union would arrive in about half an hour. The president would have no more than twenty minutes to decide whether to retaliate — and would probably have a lot less time than that. With each passing minute, the pressure to “use it or lose it” would grow stronger. And the time constraints would increase the risk of errors. The reliability of America’s early-warning system attained an existential importance. If the sensors failed to detect a Soviet attack, the order to launch might never be given. But if they issued an attack warning erroneously, millions of people would be killed by mistake.

The Pentagon decision to provide the United States with a nuclear hair trigger, capable of being fired at a moment’s notice, oddly coincided with the warmest relations between the two superpowers since the end of the Second World War. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 hadn’t raised tensions between the two Germanys, inspired massive demonstrations against the Soviet Union, or provoked much European revulsion toward communism. On the contrary, the overthrow of a moderate Czech government had encouraged Willy Brandt, the foreign minister of West Germany at the time, to seek closer ties with the Soviet Union. The status quo in Europe, the division between East and West, would not be challenged.

Читать дальше