The word ‘osobyi’ is translated as ‘special’, but the English definition does not give the full sense of its Russian usage. In the Soviet secret services, osobyi (the singular of osobye ) was used to describe a department whose specific functions required concealment. However, in the Soviet security services the acronym ‘OO’ was never used for anything but military counterintelligence. In addition to the OO in the VCheKa headquarters in Moscow, there were OOs of fronts (as the army groups are called in Russia in wartime), OOs in the armies, and Special Sections in divisions. The regional VCheKa branches, the so-called GubCheKas, also had OOs. 13

The task of the OOs was ‘fighting counterrevolution and espionage within the army and fleet’. 14In other words, the Bolsheviks were more concerned about finding enemies of the regime among its own military than about catching enemy agents. This attitude explains why, during the whole of the Soviet era, military counterintelligence was part of security services, and was within the armed forces only during SMERSH’s three-year existence and for one other very brief period, and then only formally.

During the Civil War (1918–22) that followed the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks had no choice but to draft czarist officers into the Red Army. 15Although the loyalty of these officers was obviously an issue, their military training and experience were critical during that war. But with the success of the Red Army in the war, the czarist officers became less dangerous to Stalin than the young Red Army commanders who adored his archenemy Leon Trotsky.

From 1918 till 1925, Trotsky was Commissar for Military (and Naval) Affairs; later this post was called the Defense Commissar. A talented orator (contrary to Stalin, who spoke Russian with a heavy Georgian accent; Stalin’s real last name was Dzhugashvili), Trotsky was extremely popular among the Red Army commanders. Taking into consideration that in November 1920, the Red Army and Navy had 5,430,000 servicemen, and even after a partial demobilization in January 1922 numbered 1,350,000, the number of enthusiastic Trotsky supporters was very high. 16Also, Stalin’s failure as a military commander during the Civil War made him especially jealous of Trotsky’s popularity. 17

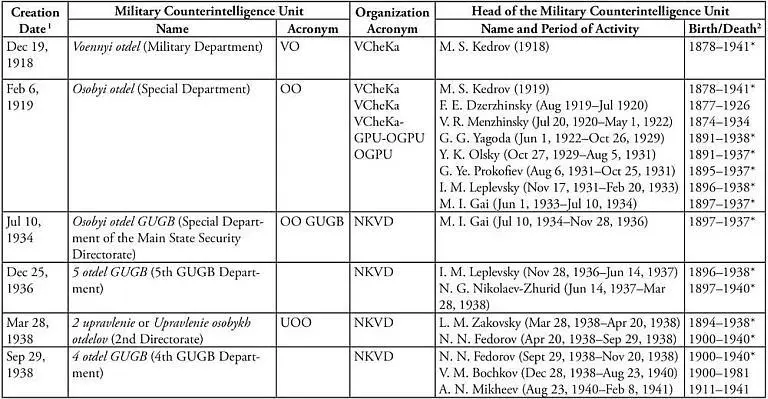

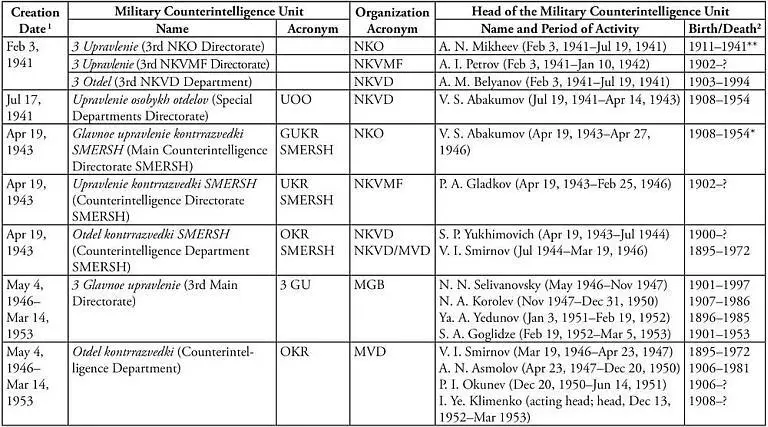

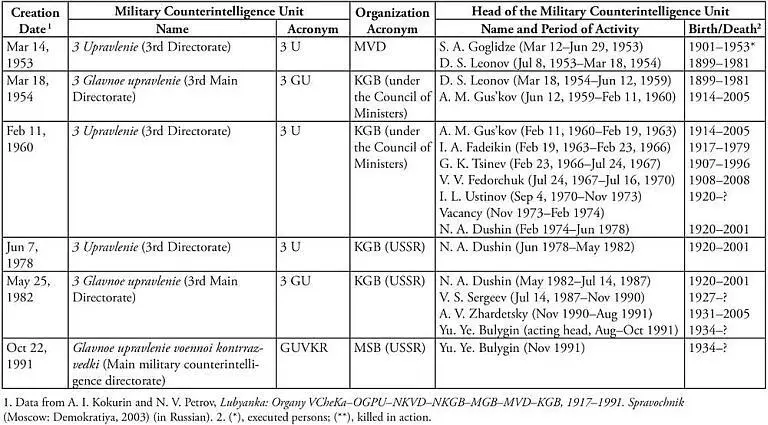

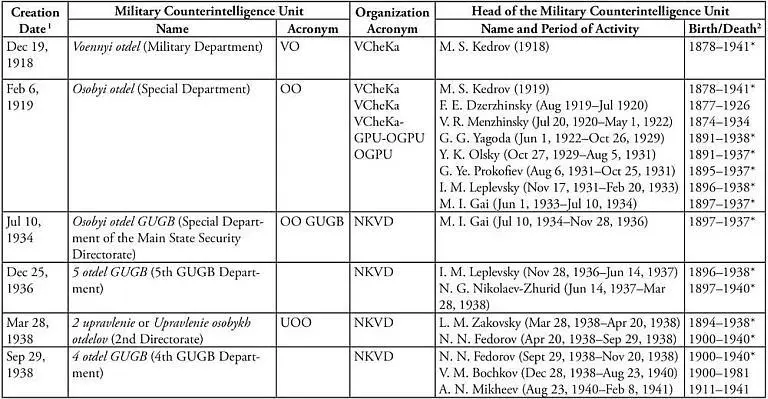

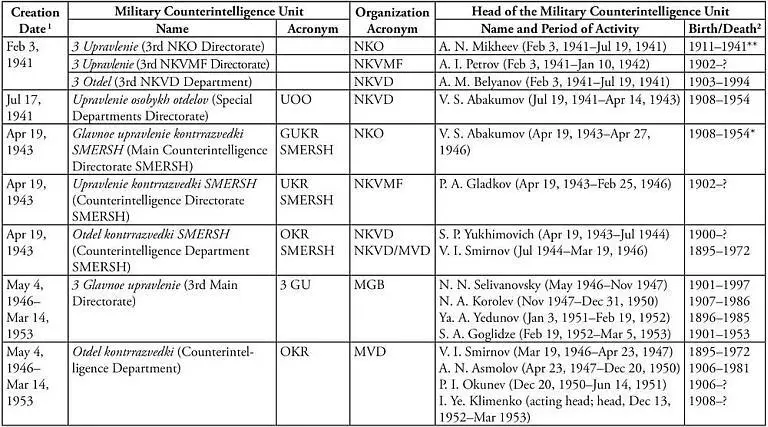

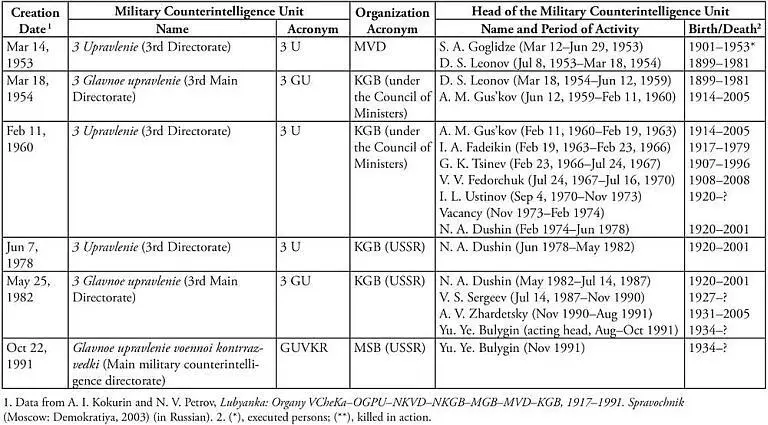

TABLE 1-2. SOVIET AND RUSSIAN FEDERATION MILITARY COUNTERINTELLIGENCE ORGANIZATIONS

In the meantime, in 1922, due to Lenin’s illness (he suffered from a progressive paralysis), the Politburo, the Party’s governing group, elected Stalin General Secretary, i.e. leader of the Bolshevik Party. 18Trotsky formed an opposition group which resulted in a long struggle between Stalin and Trotsky. In 1927, Trotsky lost all his posts, and two years later he was expelled from the Soviet Union. Finally, on Stalin’s order, he was assassinated in 1940 by an NKVD ( Narodnyi komissariat vnutrennikh del or People’s Internal Affairs Commissariat) killing squad.

Stalin never forgot Trotsky’s supporters, the ‘Trotskyists’, especially among the armed forces. They were constantly persecuted, even after World War II. 19Possibly, Stalin’s fear that the officers who served under Trotsky remained his secret supporters despite Trotsky’s political defeat was behind Stalin’s distrust of the military and his expectation that it would organize plots against him. In fact, there were no military plots; if alleged ‘plots’ were discovered by the OO, they were OO fabrications to please Stalin.

During the Civil War the OO was considered so important that from August 1919 to July 1920, Dzerzhinsky, chairman of the VCheKa, and from July 1920 to May 1922, his deputy Vyacheslav Menzhinsky, headed the OO in Moscow (Table 1-2). 20However, from the beginning, the special OO departments were involved in campaigns that were not strictly military. The first OO chief, Mikhail Kedrov, executed civilians, including children, who were suspected of counterrevolutionary activity during the civil war. Military counterintelligence also participated in the creation of phony anti-Soviet underground organizations aimed at misleading White Russians who were living abroad, often trapping emissaries sent to the Soviet Union by those Russian émigrés. In the late 1920s to early 1930s, it was also involved in rounding up and sending into exile independent farming families known as kulaks during the organization of the kolkhozy (collective farms). 21

In the 1920s–early 1930s, the OO played a special role in the VCheKa/NKVD. Almost all its leaders (Table 1-2) were later appointed to leading positions in other branches of the security services. Menzhinsky succeeded Dzerzhinsky after the latter died in 1926, and Genrikh Yagoda, once Menzhinsky’s deputy and OO head from 1922–29, became the first NKVD Commissar in 1934. 22On December 20, 1920, foreign intelligence, part of the OO, became a separate Inostrannyi otdel or INO (Foreign Department; later the all-powerful First Directorate, and currently, Sluzhba vneshnei razvedki , SVR or Foreign Intelligence Service). On July 7, 1922, the OO was divided in two parts, the OO (counterintelligence in the armed forces) and Kontrrazvedyvatel’nyi otdel or KRO (Counterintelligence Department; later the Second Directorate) in charge of internal counterintelligence, i.e. capturing spies and White Guard agents.

Artur Artuzov (born Frauchi), a long-time officer of the OO, was appointed head of the KRO. 23Vasilii Ulrikh, also an OO officer and the future chairman of the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court, became his deputy. 24However, from 1927 to 1931, the OO and KRO existed as a united structure with a joint secretariat. It was headed by Yan Olsky, who headed army OO departments during the Civil War and then became Artuzov’s deputy in the KRO (Table 1-2). 25

Through the beginning of World War II the OOs were part of the VCheKa’s successors, first the OGPU and then the NKVD, and military counterintelligence was focused on the destruction of military professionals whom Stalin did not trust or hated. In 1927, he ordered Menzhinsky, the OGPU chairman, ‘to pay special attention to espionage in the army, aviation, and the fleet’. 26

In 1928, the OGPU prepared the first show trial, the so-called Shakhtinskoe delo (Mining Case) against top-level mining engineers in the Donbass Region (currently, Ukraine) and foreigners working in the coal-mining industry. 27Yefim Yevdokimov, OGPU Plenipotentiary (representative) in the Donbass Region, persuaded Stalin that the numerous accidents in the Donbass coal mines were the result of sabotage. Allegedly, the accidents were organized by a group of engineers, who had worked in the mining industry in pre-revolutionary times, and foreign specialists. 28According to Yevdokimov, these vrediteli (from the Russian verb vredit ’ or to spoil; in English the word vrediteli is usually translated as ‘wreckers’) followed orders from the former owners of the mines who now lived abroad. The idea of sabotage conducted by wreckers played an important role in Soviet ideology and propaganda and was usually applied to members of the technical intelligentsia and other professionals. Stalin ordered arrests, and 53 engineers and managers were duly apprehended.

During the investigation, the OGPU worked out principles that were followed for all subsequent political cases until Stalin’s death. Before making the arrests, investigators invented a plot based on operational materials received from secret informers. This was not difficult because, beginning in the VCheKa’s time, the Chekists’ work, especially that of military counterintelligence, was based on reports from numerous secret informers. Thus the OGPU and its successors always had a lot of information about an enormous number of people and could easily fabricate any kind of ‘counterrevolutionary’ group. After the alleged perpetrators were arrested, the investigators’ job was to force the arrestees to ‘confess’ and sign the concocted ‘testimonies’. Since during interrogations new individuals were drawn in (during interrogations, people were forced to name their friends and coworkers), the case could snowball.

Читать дальше