In February 1941, Stalin reorganized the security services in response to the new circumstances. The huge, unwieldy NKVD was divided into three parts. Military counterintelligence was transferred to the NKO (Defense Commissariat); a new organization, the NKGB (State Security Commissariat), became responsible for foreign intelligence; and the KRO ran domestic counterintelligence, among other things. Possibly, if not for the war, the NKGB would have continued the mass arrests of the Red Terror period since by March 1941, it had a cardfile for 1,263,000 ‘anti-Soviet elements’ who potentially could have been arrested. 44The NKVD was left to manage the slave labor in the camps and provide special troops to support NKGB actions in the newly occupied territory. It was also tasked with creating a separate system of camps for foreign prisoners of war.

Stalin was now ready to order his troops to continue their march to the West, but the unexpected invasion of Russia by Adolf Hitler’s troops on June 22, 1941 scuttled all his plans. During the disastrous and chaotic first months of World War II, the focus of the state security services returned to controlling the Soviet Union’s own citizens, many of whom at first greeted the Germans as liberators. Stalin undid his February changes, and recreated a huge NKVD.

Military counterintelligence was transferred back to the NKVD in the form of the OO Directorate, or the UOO (the ‘U’ means ‘Directorate’, which indicated that the OO had become a larger organization), and was given a new chief, the rising star Viktor Abakumov. Abakumov had already demonstrated his efficiency early in 1941, when he participated in the purging of the Baltic States. During this first period of World War II, the main goal of military counterintelligence was to prevent desertions and to vet the vast numbers of servicemen who had been surrounded or captured by the fast-advancing Germans.

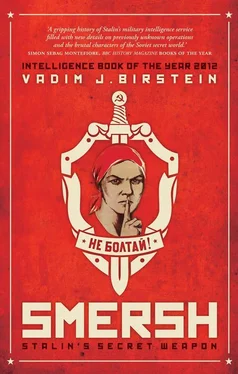

In the spring of 1943, with the success of the Red Army in Stalingrad, it became clear that the war was finally becoming an offensive one. The Red Army began to liberate Nazi-occupied Soviet territory and prepared to advance into Europe. At this point, Stalin returned to the tripartite organization of the secret services of early 1941, with the military counterintelligence directorate now rechristened SMERSH and formally made a part of the NKO. In essence, SMERSH was simply the UOO, renamed and made independent of the main body of secret services. Abakumov, the UOO’s head, became head of SMERSH, and most of the UOO’s personnel were also transferred. SMERSH’s staff was considerably larger than the UOO’s.

SMERSH differed from the UOO in another extremely important aspect—Abakumov reported directly to Stalin, because Stalin had special plans for SMERSH. The Soviet dictator needed an organization he personally controlled to help him politically consolidate the territorial gains he expected the Red Army to make in Eastern Europe and Germany. Therefore, SMERSH was truly Stalin’s secret weapon—a weapon that was even more effective than tanks and bombs in conquering new territory in the West.

By the time of SMERSH’s creation, Stalin was the all-powerful dictator of the Soviet Union. He was general secretary of the Communist Party, chairman of the Council of Commissars, chairman of the wartime GKO (State Defense Committee), Defense Commissar, and commander in chief of the armed forces.

The order from Stalin that created SMERSH on April 19, 1943 was marked ‘ss’ (two small Russian ‘s’ letters, an acronym for sovershenno sekretno or Top Secret). 45A quotation from the order detailing SMERSH’s responsibilities conveys a deep distrust of the Red Army, and its last point makes clear that SMERSH was to play a special role:

The ‘SMERSH’ organs are charged with the following:

a) combating spy, diversion, terrorist, and other subversive activity of foreign intelligence in the units and organizations of the Red Army;

b) combating anti-Soviet elements that have penetrated into the units and organizations of the Red Army;

c) taking the necessary agent-operational [i.e., through informers] and other (through commanding officers) measures for creating conditions at the fronts to prevent enemy agents from crossing the front line and to make the front line impenetrable to spies and anti-Soviet elements;

d) combating traitors of the Motherland in the units and organizations of the Red Army (those who have gone over to the enemy side, who hide spies or provide any help to spies);

e) combating desertion and self-mutilation at the fronts;

f) investigating servicemen and other persons who have been taken prisoner of war or have been surrounded by the enemy;

g) conducting special tasks for the People’s Commissar of Defense. 46

Due to the secrecy surrounding SMERSH, at first even officers in the field did not know SMERSH’s real name. Daniil Fibikh, a journalist working for a military newspaper at the Northwestern Front, wrote in his diary: ‘Special detachments SSSh—“ Smert’, smert’ shpionam ” [“Death, death to spies”] (!) [an exclamation mark in the original] attached to the Special Departments have been organized.’ 47In June 1943 Fibikh found out what this organization was about. SMERSH operatives arrested him for ‘disseminating anti-Soviet propaganda’ (Article 58-10 of the Criminal Code) after a secret informer reported on Fibikh’s critical remarks regarding the Red Army. Fibikh was sentenced to a ten-year imprisonment in the labor camps.

Soon the ruthlessness of SMERSH interrogators became legendary. The investigative officers, known as ‘ smershevtsy ’, tortured and killed thousands of people whether they were guilty of intelligence activity or not. Two Soviet defectors who served in SMERSH published littleknown English-language memoirs in which they described the horrific interrogation methods. 48In one of these books, Nicola Sinevirsky, a military translator, wrote how he was forced to witness a brutal beating by a female SMERSH officer:

The Pole did not answer. Galya moved closer to him. She moved the rubber hose slowly back and forth in front of his face. ‘Don’t make yourself a bigger fool than you are already. Is that clear?’

The Pole looked around helplessly and said, ‘I don’t understand you.’

I translated Galya’s words to the prisoner. As I did so, Galya broke in, ‘He lies! The son of a bitch! He understands, all right! There is more cunning in him than in all of Poland. Listen to me, you Polish pig!’ Galya screamed, raising the rubber hose above her head…

Galya beat the Pole across the face unceasingly. ‘I’ll beat you bloody. I’ll beat you until you confess or you die on this spot!’ A torrent of coarse oaths burst from Galya’s lips…

The Pole’s face was beaten into a formless mass of flesh and blood. Blood dripped in thin streaks over his chest and on his shirt. His badly bruised eyes showed no spark of life…

The work on him was resumed where she had left off before our short break for dinner. It was four o’clock in the morning before the sentries finally carried away the broken body of the dying Pole…

Like a drunken man, I stumbled to my quarters and collapsed on my bed without undressing. In a matter of seconds, it seemed that I had slipped quietly into a heavy coma.

It took days for me to recover from the bloody apparition. 49

Each front had its own SMERSH directorate stationed at the front line with the Red Army troops, and SMERSH made wide use of informers on all levels of the Red Army and among former prisoners of war. 50SMERSH’s chain of command was completely independent of the military hierarchy, so a SMERSH officer was subordinate only to a higher-level SMERSH officer. Constant communication between SMERSH front-line units and Moscow headquarters was maintained, with Abakumov preparing daily reports for Stalin.

Читать дальше