45. Only recently were several truthful memoirs about these events published, including Nikolai I. Obryn’ba, The Memoirs of a Soviet Resistance Fighter on the Eastern Front , translated by Vladimir Kupnik (Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2007), and Vladimir Shimkevich, Sud’ba moskovskogo opolchentsa. Front, okruzhenie, plen. 1941–1945 (Moscow: Tsentrpoligraf, 2008) (in Russian).

46. Aleksandr Melenberg, ‘Pobeda. Vremya posle bedy. Chast’ III. L’goty veteranam Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny v instruktsiyakh i postanovleniyakh vlasti,’ Novaya gazeta , tsvetnoi vypusk 17 (May 11, 2007) (in Russian). http://www.novayagazeta.ru/data/2007/color17/07.html, retrieved September 4, 2011.

47. The denial intensified after the publication in 2005 of the Russian translation of Antony Beevor’s The Fall of Berlin 1945 (New York: Viking, 2002), see S. Turchenko, ‘Nasilie nad faktami,’ Trud , July 21, 2005 (in Russian). Beevor’s Russian opponents ignored the fact that Beevor cited Soviet documents from the Russian military archive.

48. For instance, a discussion in Mark Solonin, Net blaga na voine (Moscow: Yauza-Press, 2010), 180–264 (in Russian).

49. N. N. Nikoulin, Vospominaniya o voine (St. Petersburg: Izdatel’stvo Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha, 2008), 41–42 (in Russian).

CHAPTER 1

Soviet Military Counterintelligence: An Overview

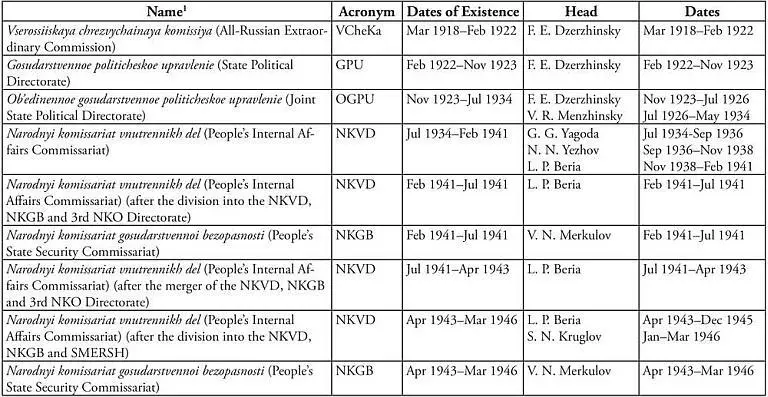

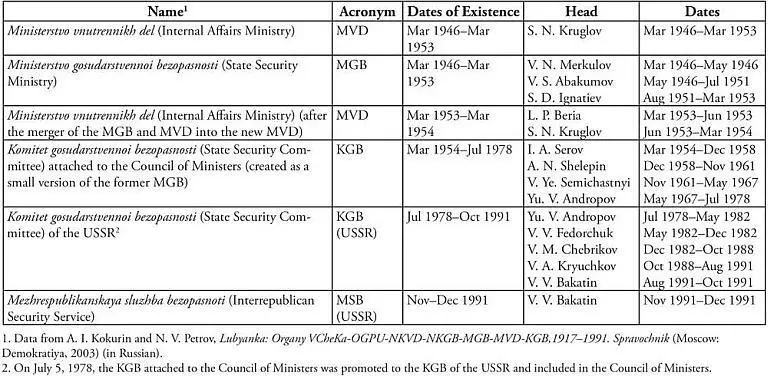

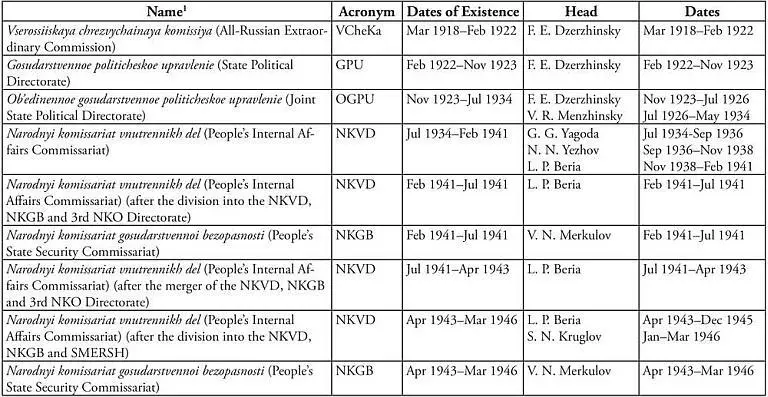

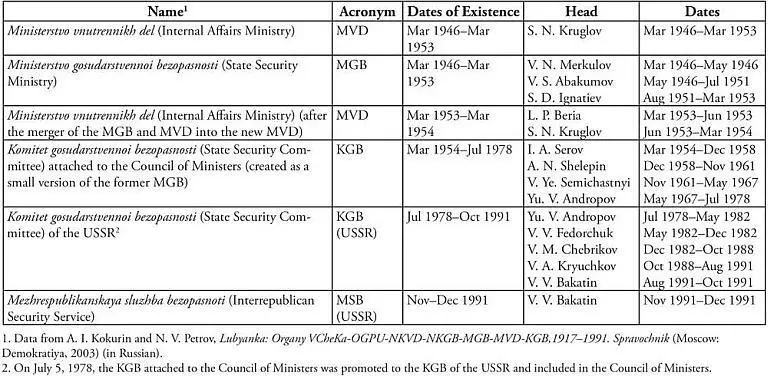

The history of SMERSH is so intimately intertwined with the many skeins of Soviet political and secret service history I decided to start out this volume with a short overview of Soviet military counterintelligence and its place in the larger landscape of the Soviet Union. Hopefully this will serve to keep the reader oriented in the chapters that follow, where detailed explanations of the many byzantine cabals of Stalin and other political and secret service figures are necessary to illuminate the dark history of SMERSH. And as an aid to keeping track of the many confusing transformations and personnel changes in the secret services, I have provided a listing of the various organizations (Table 1-1).

It all began on November 7, 1917 when the Bolshevik Party organized a coup known as the October Revolution and took over political power in Russia. The Party was small, consisting of about 400,000 members in a country with a population of over 100 million. 1Soon the Bolshevik government was on the verge of collapse. The troops of the Cossack Ataman (Leader) Pyotr Krasnov and the White Army of General Anton Denikin were threatening the new Russian Republic from the South, Ukraine and the Baltic States were occupied by the Germans, and Siberia was in the hands of anti-Soviet Czechoslovak WWI POWs.

But the numerous peasant revolts that erupted throughout Bolshevik-controlled territory were even more dangerous for them. In these circumstances Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik leader, unleashed terror to hang onto power. On December 20, 1917, the first Soviet secret service, the VCheKa ( Vserossiiskaya Chrezvychainaya Komissiya po bor’be s kontrrevolyutsiei i sabotazhem or All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage), attached to the SNK ( Sovet Narodnykh Komissarov or Council of People’s Commissars, i.e. the Bolshevik government) was created. 2The VCheKa’s task was ‘to stop and liquidate counterrevolutionary and diversion activity’ and ‘to put on trial in the Revolutionary tribunal those who had committed sabotage acts and the counterrevolutionaries, and to develop methods for fighting them’. Since this time and to the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, through the VCheKa and its successors, a comparatively small Bolshevik (later Communist) Party controlled the large population of Russia (later the Soviet Union) through intimidation and terror. In Lenin’s terminology, this method of control was called ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’. 3But, in fact, the Bolshevik’s tactics were the same as those of any organized criminal or fascist group, such as the Italian Mafia and the Nazi Party in Germany. 4

TABLE 1-1. SOVIET SECURITY SERVICES AND THEIR HEADS

The VCheKa, headed by Felix Dzerzhinsky, a Bolshevik from a family of minor Polish nobility, who as a teenager dreamed of becoming a Catholic priest, consisted of only 12 members. On September 2, 1918, the VCheKa issued ‘The Red Terror Order’ to arrest and imprison members of socialist non-Bolshevik parties. 5Additionally, all big industrialists, businessmen, merchants, noble-landowners, ‘counterrevolutionary priests’, and ‘officers hostile to the Soviet government’ were to be placed into concentration camps and forced to work there. Any attempt to resist was punished by immediate execution.

Three days later the SNK issued an additional decree, entitled ‘On the Red Terror’. 6It ordered an increase in VCheKa staff (known from then on as the Chekisty ) culled from the ranks of devoted Bolsheviks. Within a year the VCheKa became an organization with a headquarters in Moscow and branches throughout the whole country. The SNK decree also ordered ‘to isolate the class enemies in concentration camps; to shoot to death every person close to the organizations of White Guardists [members of the White armies], plots and revolts; to publish the names of the executed, as well as an explanation why they had been executed’. The Red Terror was in full swing, and during its first two months alone, at least 10,000–15,000 victims were executed. 7Very soon Dzerzhinsky, a brutal workaholic with an ascetic lifestyle, earned his nickname ‘Iron Felix’. 8

The first decrees set up the objectives, rules, and even phraseology for the future Soviet security services. Any real or potential threat to Bolshevik power became a ‘counterrevolutionary crime’, and later, in Joseph Stalin’s Criminal Code of 1926, these ‘crimes’ comprised fourteen paragraphs (treason, espionage, subversion, assistance to the world bourgeoisie, etc.) of the infamous Article 58. The perpetrators of such crimes, soon called ‘enemies of the working people’, were found mostly among former bourgeoisie, nobles, and any professional or educated person. However, there were also numerous workers and peasants among the victims of the Red Terror. Relatives of persons sought for counterrevolutionary crimes were also often arrested. This practice was formalized in Stalin’s time, when legal convictions of relatives of ‘enemies of the people’ became a standard practice. It’s important to note that only the VCheKa and its successor organizations were allowed investigate ‘counterrevolutionary crimes’.

Already in these first decrees there was a category of enemies called ‘the hostile officers’, which was the beginning of Lenin’s and then Stalin’s suspicious attitude to the professional military. In fact, detachments of revolutionary soldiers and sailors (as the navy privates are called in Russia) played a critical role in the Bolshevik coup. Very few high army and navy officers joined these detachments or supported the Bolsheviks.

On January 28, 1918, the SNK declared the creation of the Red Army and by February 23, which was later announced as the Red Army’s birthday, some detachments of the new army had been formed. 9On December 19, 1918, the first military counterintelligence organization, the VO ( Voennyi otdel or Military Department), was established within the VCheKa (Table 1-2). 10It included previous counterintelligence organizations that existed in the armies in the field. 11On January 1, 1919, the VO was renamed Osobyi otdel (Special Department) or the OO. This name was definitely reminiscent of the political police of the czarist time, when Osobyi otdel within Departament politsii or the Police Department investigated crimes against the state such as the activities of revolutionary parties, foreign espionage, and treason. 12

Читать дальше