Rachel Carson - The Edge of the Sea

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rachel Carson - The Edge of the Sea» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Boston, Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: Mariner Books, Жанр: Биология, sci_ecology, sci_popular, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Edge of the Sea

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mariner Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- Город:Boston

- ISBN:978-0-395-07505-0

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Edge of the Sea: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Edge of the Sea»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A book to be read for pleasure as well as a practical identification guide,

introduces a world of teeming life where the sea meets the land. A new generation of readers is discovering why Rachel Carson’s books have become cornerstones of the environmental and conservation movements. New introduction by Sue Hubbell.

The Edge of the Sea — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Edge of the Sea», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In none of these examples can we be sure whether the animal is responding to the tides or, as the tides themselves do, to the influence of the moon. With plants, however, the situation is different, and here and there we find scientific confirmation of the ancient and world-wide belief in the effect of moonlight on vegetation. Various bits of evidence suggest that the rapid multiplication of diatoms and other members of the plant plankton is related to the phases of the moon. Certain algae in river plankton reach the peak of their abundance at the full moon. One of the brown seaweeds on the coast of North Carolina releases its reproductive cells only on the full moon, and similar behavior has been reported for other seaweeds in Japan and other parts of the world. These responses are generally explained as the effect of varying intensities of polarized light on protoplasm.

Other observations suggest some connection between plants and the reproduction and growth of animals. Rapidly maturing herring collect around the edge of concentrations of plant plankton, although the fully adult herring may avoid them. Spawning adults, eggs, and young of various other marine creatures are reported to occur more often in dense phytoplankton than in sparse patches. In significant experiments, a Japanese scientist discovered he could induce oysters to spawn with an extract obtained from sea lettuce. The same seaweed produces a substance that influences growth and multiplication of diatoms, and is itself stimulated by water taken from the vicinity of a heavy growth of rockweeds.

The whole subject of the presence in sea water of the so-called “ectocrines” (external secretions or products of metabolism) has so recently become one of the frontiers of science that actual information is fragmentary and tantalizing. It appears, however, that we may be on the verge of solving some of. the riddles that have plagued men’s minds for centuries. Though the subject lies in the misty borderlands of advancing knowledge, almost everything that in the past has been taken for granted, as well as problems considered insoluble, bear renewed thought in the light of the discovery of these substances.

In the sea there are mysterious comings and goings, both in space and time: the movements of migratory species, the strange phenomenon of succession by which, in one and the same area, one species appears in profusion, flourishes for a time, and then dies out, only to have its place taken by another and then another, like actors in a pageant passing before our eyes. And there are other mysteries. The phenomenon of “red tides” has been known from early days, recurring again and again down to the present time—a phenomenon in which the sea becomes discolored because of the extraordinary multiplication of some minute form, often a dinoflagellate, and in which there are disastrous side effects in the shape of mass mortalities among fish and some of the invertebrates. Then there is the problem of curious and seemingly erratic movements of fish, into or away from certain areas, often with sharp economic consequences. When the so-called “Atlantic water” floods the south coast of England, herring become abundant within the range of the Plymouth fisheries, certain characteristic plankton animals occur in profusion, and certain species of invertebrates flourish in the intertidal zone. When, however, this water mass is replaced by Channel water, the cast of characters undergoes many changes.

In the discovery of the biological role played by the sea water and all it contains, we may be about to reach an understanding of these old mysteries. For it is now clear that in the sea nothing lives to itself. The very water is altered, in its chemical nature and in its capacity for influencing life processes, by the fact that certain forms have lived within it and have passed on to it new substances capable of inducing far-reaching effects. So the present is linked with past and future, and each living thing with all that surrounds it.

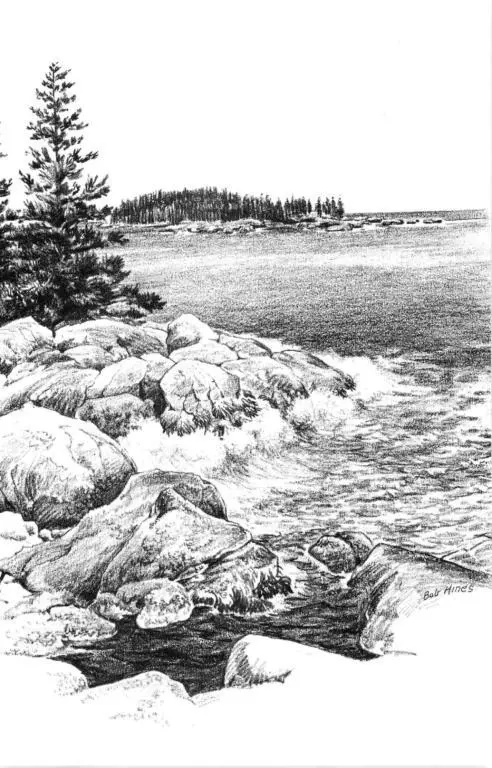

III. The Rocky Shores

WHEN THE TIDE is high on a rocky shore, when its brimming fullness creeps up almost to the bayberry and the junipers where they come down from the land, one might easily suppose that nothing at all lived in or on or under these waters of the sea’s edge. For nothing is visible. Nothing except here and there a little group of herring gulls, for at high tide the gulls rest on ledges of rock, dry above the surf and the spray, and they tuck their yellow bills under their feathers and doze away the hours of the rising water. Then all the creatures of the tidal rocks are hidden from view, but the gulls know what is there, and they know that in time the water will fall away again and give them entrance to the strip between the tide lines.

When the tide is rising the shore is a place of unrest, with the surge leaping high over jutting rocks and running in lacy cascades of foam over the landward side of massive boulders. But on the ebb it is more peaceful, for then the waves do not have behind them the push of the inward pressing tides. There is no particular drama about the turn of the tide, but presently a zone of wetness shows on the gray rock slopes, and offshore the incoming swells begin to swirl and break over hidden ledges. Soon the rocks that the high tide had concealed rise into view and glisten with the wetness left on them by the receding water.

Small, dingy snails move about over rocks that are slippery with the growth of infinitesimal green plants; the snails scraping, scraping, scraping to find food before the surf returns.

Like drifts of old snow no longer white, the barnacles come into view; they blanket rocks and old spars wedged into rock crevices, and their sharp cones are sprinkled over empty mussel shells and lobster-pot buoys and the hard stipes of deep-water seaweeds, all mingled in the flotsam of the tide.

Meadows of brown rockweeds appear on the gently sloping rocks of the shore as the tide imperceptibly ebbs. Smaller patches of green weed, stringy as mermaids’ hair, begin to turn white and crinkly where the sun has dried them.

Now the gulls, that lately rested on the higher ledges, pace with grave intentness along the walls of rock, and they probe under the hanging curtains of weed to find crabs and sea urchins.

In the low places little pools and gutters are left where the water trickles and gurgles and cascades in miniature waterfalls, and many of the dark caverns between and under the rocks are floored with still mirrors holding the reflections of delicate creatures that shun the light and avoid the shock of waves—the cream-colored flowers of the small anemones and the pink fingers of soft coral, pendent from the rocky ceiling.

In the calm world of the deeper rock pools, now undisturbed by the tumult of incoming waves, crabs sidle along the walls, their claws busily touching, feeling, exploring for bits of food. The pools are gardens of color composed of the delicate green and ocher-yellow of encrusting sponge, the pale pink of hydroids that stand like clusters of fragile spring flowers, the bronze and electric-blue gleams of the Irish moss, the old-rose beauty of the coralline algae.

And over it all there is the smell of low tide, compounded of the faint, pervasive smell of worms and snails and jellyfish and crabs—the sulphur smell of sponge, the iodine smell of rockweed, and the salt smell of the rime that glitters on the sun-dried rocks.

One of my own favorite approaches to a rocky seacoast is by a rough path through an evergreen forest that has its own peculiar enchantment. It is usually an early morning tide that takes me along that forest path, so that the light is still pale and fog drifts in from the sea beyond. It is almost a ghost forest, for among the living spruce and balsam are many dead trees-some still erect, some sagging earthward, some lying on the floor of the forest. All the trees, the living and the dead, are clothed with green and silver crusts of lichens. Tufts of the bearded lichen or old man’s beard hang from the branches like bits of sea mist tangled there. Green woodland mosses and a yielding carpet of reindeer moss cover the ground. In the quiet of that place even the voice of the surf is reduced to a whispered echo and the sounds of the forest are but the ghosts of sound—the faint sighing of evergreen needles in the moving air; the creaks and heavier groans of half-fallen trees resting against their neighbors and rubbing bark against bark; the light rattling fall of a dead branch broken under the feet of a squirrel and sent bouncing and ricocheting earthward.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Edge of the Sea»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Edge of the Sea» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Edge of the Sea» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.