Rachel Carson - The Edge of the Sea

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rachel Carson - The Edge of the Sea» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Boston, Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: Mariner Books, Жанр: Биология, sci_ecology, sci_popular, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Edge of the Sea

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mariner Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- Город:Boston

- ISBN:978-0-395-07505-0

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Edge of the Sea: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Edge of the Sea»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A book to be read for pleasure as well as a practical identification guide,

introduces a world of teeming life where the sea meets the land. A new generation of readers is discovering why Rachel Carson’s books have become cornerstones of the environmental and conservation movements. New introduction by Sue Hubbell.

The Edge of the Sea — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Edge of the Sea», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

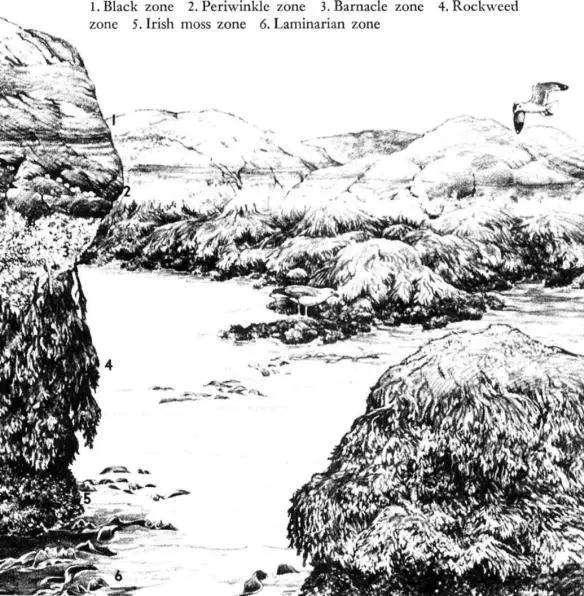

As day after day these great tides ebb and flow over the rocky rim of New England, their progress across the shore is visibly marked in stripes of color running parallel to the sea’s edge. These bands, or zones, are composed of living things and reflect the stages of the tide, for the length of time that a particular level of shore is uncovered determines, in large measure, what can live there. The hardiest species live in the upper zones. Some of the earth’s most ancient plants—the blue-green algae—though originating eons ago in the sea, have emerged from it to form dark tracings on the rocks above the high-tide line, a black zone visible on rocky shores in all parts of the world. Below the black zone, snails that are evolving toward a land existence browse on the film of vegetation or hide in seams and crevices in the rocks. But the most conspicuous zone begins at the upper line of the tides. On an open shore with moderately heavy surf, the rocks are whitened by the crowded millions of the barnacles just below the high-tide line. Here and there the white is interrupted by mussels growing in patches of darkest blue. Below them the seaweeds come in— the brown fields of the rockweeds. Toward the low-tide line the Irish moss spreads its low cushioning growth—a wide band of rich color that is not fully exposed by the sluggish movements of some of the neap tides, but appears on all of the greater tides. Sometimes the reddish brown of the moss is splashed with the bright green tangles of another seaweed, a hairlike growth of wiry texture. The lowest of the spring tides reveal still another zone during the last hour of their fall—that sub-tide world where all the rock is painted a deep rose hue by the lime-secreting seaweeds that encrust it, and where the gleaming brown ribbons of the large kelps lie exposed on the rocks.

With only minor variations, this pattern of life exists in all parts of the world. The differences from place to place are related usually to the force of the surf, and one zone may be largely suppressed and another enormously developed. The barnacle zone, for example, spreads its white sheets over all the upper shore where waves are heavy, and the rockweed zone is greatly reduced. With protection from surf, the rockweeds not only occupy the middle shore in profusion but invade the upper rocks and make conditions difficult for the barnacles.

Perhaps in a sense the true intertidal zone is that band between high and low water of the neap tides, an area that is completely covered and uncovered during each tidal cycle, or twice during every day. Its inhabitants are the typical shore animals and plants, requiring some daily contact with the sea but able to endure limited exposure to land conditions.

Above high water of neaps is a band that seems more of earth than of sea. It is inhabited chiefly by pioneering species; already they have gone far along the road toward land life and can endure separation from the sea for many hours or days. One of the barnacles has colonized these higher high-tide rocks, where the sea comes only a few days and nights out of the month, on the spring tides. When the sea returns it brings food and oxygen, and in season carries away the young into the nursery of the surface waters; during these brief periods the barnacle is able to carry on all the processes necessary for life. But it is left again in an alien land world when the last of these highest tides of the fortnight ebbs away; then its only defense is the firm closing of the plates of its shell to hold some of the moisture of the sea about its body. In its life brief and intense activity alternates with long periods of a quiescent state resembling hibernation. Like the plants of the Arctic, which must crowd the making and storing of food, the putting forth of flowers, and the forming of seeds into a few brief weeks of summer, this barnacle has drastically adjusted its way of life so that it may survive in a region of harsh conditions.

Some few sea animals have pushed on even above high water of the spring tides into the splash zone, where the only salty moisture comes from the spray of breaking waves. Among such pioneers are snails of the periwinkle tribe. One of the West Indian species can endure months of separation from the sea. Another, the European rock periwinkle, waits for the waves of the spring tides to cast its eggs into the sea, in almost all activities except the vital one of reproduction being independent of the water.

Below the low water of neaps are the areas exposed only as the rhythmic swing of the tides falls lower and lower, approaching the level of the springs. Of all the intertidal zone this region is linked most closely with the sea. Many of its inhabitants are offshore forms, able to live here only because of the briefness and infrequency of exposure to the air.

The relation between the tides and the zones of life is clear, but in many less obvious ways animals have adjusted their activities to the tidal rhythm. Some seem to be a mechanical matter of utilizing the movement of water. The larval oyster, for example, uses the flow of the tides to carry it into areas favorable for its attachment. Adult oysters live in bays or sounds or river estuaries rather than in water of full oceanic salinity, and so it is to the advantage of the race for the dispersal of the young stages to take place in a direction away from the open sea. When first hatched the larvae drift passively, the tidal currents carrying them now toward the sea, now toward the headwaters of estuaries or bays. In many estuaries the ebb tide runs longer than the flood, having the added push and volume of stream discharge behind it, and the resulting seaward drift over the whole two-week period of larval life would carry the young oysters many miles to sea. A sharp change of behavior sets in, however, as the larvae grow older. They now drop to the bottom while the tide ebbs, avoiding the seaward drift of water, but with the return of the flood they rise into the currents that are pressing upstream, and so are carried into regions of lower salinity that are favorable for their adult life.

Others adjust the rhythm of spawning to protect their young from the danger of being carried into unsuitable waters. One of the tube-building worms living in or near the tidal zone follows a pattern that avoids the strong movements of the spring tides. It releases its larvae into the sea every fortnight on the neap tides, when the water movements are relatively sluggish; the young worms, which have a very brief swimming stage, then have a good chance of remaining within the most favorable zone of the shore.

There are other tidal effects, mysterious and intangible. Sometimes spawning is synchronized with the tides in a way that suggests response to change of pressure or to the difference between still and flowing water. A primitive mollusk called the chiton spawns in Bermuda when the low tide occurs early in the morning, with the return flow of water setting in just after sunrise. As soon as the chitons are covered with water they shed their spawn. One of the Japanese nereid worms spawns only on the strongest tides of the year, near the new- and full-moon tides of October and November, presumably stirred in some obscure way by the amplitude of the water movements.

Many other animals, belonging to quite unrelated groups throughout the whole range of sea life, spawn according to a definitely fixed rhythm that may coincide with the full moon or the new moon or its quarters, but whether the effect is produced by the altered pressure of the tides or the changing light of the moon is by no means clear. For example, there is a sea urchin in Tortugas that spawns on the night of the full moon, and apparently only then. Whatever the stimulus may be, all the individuals of the species respond to it, assuring the simultaneous release of immense numbers of reproductive cells. On the coast of England one of the hydroids, an animal of plant-like appearance that produces tiny medusae or jellyfish, releases these medusae during the moon’s third quarter. At Woods Hole on the Massachusetts coast a clamlike mollusk spawns heavily between the full and the new moon but avoids the first quarter. And a nereid worm at Naples gathers in its nuptial swarms during the quarters of the moon but never when the moon is new or full; a related worm at Woods Hole shows no such correlation although exposed to the same moon and to stronger tides.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Edge of the Sea»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Edge of the Sea» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Edge of the Sea» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.