We hold the URL to the National Weather Service XML in a string resource, and pour in the latitude and longitude at runtime. Given our HttpClientobject created in onCreate(), we populate an HttpGetwith that customized URL, then execute that method. Given the resulting XML from the REST service, we build the forecast HTML page (see “Parsing Responses”) and pour that into the WebKitwidget. If the HttpClientblows up with an exception, we provide that error as a Toast.

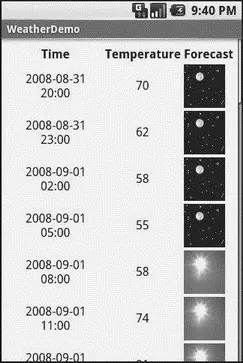

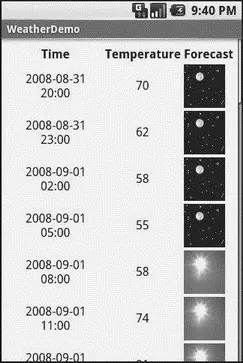

The response you get will be formatted using some system — HTML, XML, JSON, whatever. It is up to you, of course, to pick out what information you need and do something useful with it. In the case of the WeatherDemo, we need to extract the forecast time, temperature, and icon (indicating sky conditions and precipitation) and generate an HTML page from it.

Android includes:

• Three XML parsers: the traditional W3C DOM ( org.w3c.dom), a SAX parser ( org.xml.sax), and the XML pull parser discussed in Chapter 19

• A JSON parser ( org.json)

You are also welcome to use third-party Java code, where possible, to handle other formats, such as a dedicated RSS/Atom parser for a feed reader. The use of third-party Java code is discussed in Chapter 21.

For WeatherDemo, we use the W3C DOM parser in our buildForecasts()method:

void buildForecasts(String raw) throwsException {

DocumentBuilder builder = DocumentBuilderFactory

. newInstance(). newDocumentBuilder();

Document doc = builder. parse( new InputSource( new StringReader(raw)));

NodeList times = doc. getElementsByTagName("start-valid-time");

for(int i=0; igetLength(); i++) {

Element time = (Element)times. item(i);

Forecast forecast = new Forecast();

forecasts. add(forecast);

forecast. setTime(time. getFirstChild(). getNodeValue());

}

NodeList temps = doc. getElementsByTagName("value");

for(int i=0; igetLength(); i++) {

Element temp = (Element)temps. item(i);

Forecast forecast = forecasts. get(i);

forecast. setTemp( new Integer(temp. getFirstChild(). getNodeValue()));

}

NodeList icons = doc. getElementsByTagName("icon-link");

for(int i=0; igetLength(); i++) {

Element icon = (Element)icons. item(i);

Forecast forecast = forecasts. get(i);

forecast. setIcon(icon. getFirstChild(). getNodeValue());

}

}

The National Weather Service XML format is… curiously structured, relying heavily on sequential position in lists versus the more object-oriented style you find in formats like RSS or Atom. That being said, we can take a few liberties and simplify the parsing somewhat, taking advantage of the fact that the elements we want ( start-valid-timefor the forecast time, value for the temperature, and icon-linkfor the icon URL) are all unique within the document.

The HTML comes in as an InputStreamand is fed into the DOM parser. From there, we scan for the start-valid-timeelements and populate a set of Forecastmodels using those start times. Then, we find the temperature value elements and icon-linkURLs and fill those into the Forecastobjects.

In turn, the generatePage()method creates a rudimentary HTML table with the forecasts:

String generatePage() {

StringBuffer bufResult = new StringBuffer("

");

bufResult. append("

" +

"

");

for(Forecast forecast : forecasts) {

bufResult. append("

bufResult. append(forecast. getTime());

bufResult. append("

bufResult. append(forecast. getTemp());

bufResult. append("

bufResult. append(forecast. getIcon());

bufResult. append("\">

");

}

bufResult. append("

| Time |

Temperature |

Forecast |

| "); |

"); |

|

");

return(bufResult. toString());

}

The result can be seen in Figure 22-1.

Figure 22-1. The WeatherDemo sample application

If you need to use SSL, bear in mind that the default HttpClientsetup does not include SSL support. Mostly, this is because you need to decide how to handle SSL certificate presentation — do you blindly accept all certificates, even self-signed or expired ones? Or do you want to ask the user if they really want to use some strange certificates?

Similarly, HttpClient, by default, is designed for single-threaded use. If you will be using HttpClientfrom a service or some other place where multiple threads might be an issue, you can readily set up HttpClientto support multiple threads.

For these sorts of topics, you are best served by checking out the HttpComponentsWeb site for documentation and support.

CHAPTER 23

Creating Intent Filters

Up to now, the focus of this book has been on activities opened directly by the user from the device’s launcher. This, of course, is the most obvious case for getting your activity up and visible to the user. In many cases it is the primary way the user will start using your application.

However, the Android system is based upon lots of loosely-coupled components. What you might accomplish in a desktop GUI via dialog boxes, child windows, and the like are mostly supposed to be independent activities. While one activity will be “special”, in that it shows up in the launcher, the other activities all need to be reached… somehow.

The “how” is via intents.

An intent is basically a message that you pass to Android saying, “Yo! I want to do… er… something! Yeah!” How specific the “something” is depends on the situation — sometimes you know exactly what you want to do (e.g., open up one of your other activities), and sometimes you don’t.

In the abstract, Android is all about intents and receivers of those intents. So, now that we are well-versed in creating activities, let’s dive into intents, so we can create more complex applications while simultaneously being “good Android citizens.”

Читать дальше