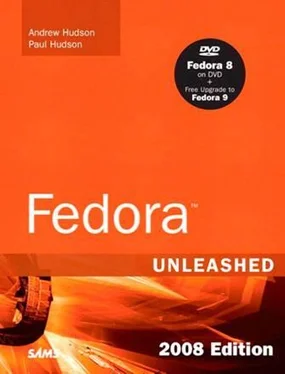

# dd if=/tmp/hdambr of=/dev/hda bs=512 count=1

To restore only the partition table, skipping the boot loader code, use this:

# dd if=/tmp/hdambr of=/dev/hda bs=1 skip=446 count=66

Of course, it would be prudent to move the copy of the MBR to a floppy disk or other appropriate storage device. (The file is only 512 bytes in size.) You will need to be able to run dd on the system to restore it (which means that you will be using the Fedora rescue disc, as described later, or any equivalent to it).

Manually Restoring the Partition Table

A different way of approaching the problem is to have a printed copy of the partition table that can then be used to restore the partition table by hand with the Fedora rescue disc and the fdiskprogram.

You can create a listing of the printout of the partition table with fdiskby using the -loption (for list), as follows:

# fdisk /dev/hda -l > /tmp/hdaconfig.txt

or send the listing of the partition table to the printer:

# fdisk /dev/hda -l | kprinter

You could also copy the file /tmp/hdaconfig.txtto the same backup floppy disk as the MBR for safekeeping.

Now that you have a hard copy of the partition table (as well as having saved the file itself somewhere), it is possible to restore the MBR by hand at some future date.

Use the Fedora Rescue Disc for this process. After booting into rescue mode, you have the opportunity to use a menu to mount your system read/write, not to mount your system, or to mount any found Linux partitions as read-only. If you plan to make any changes, you need to have any desired partitions mounted with write permission.

After you are logged on (you are root by default), start fdiskon the first drive:

# fdisk /dev/hda

Use the pcommand to display the partition information and compare it to the hard copy you have. If the entries are identical, you have a problem somewhere else; it is not the partition table. If there is a problem, use the dcommand to delete all the listed partitions.

Now use the ncommand to create new partitions that match the partition table from your hard copy. Make certain that the partition types ( ext2, FAT, swap, and so on) are the same. If you have a FATpartition at /dev/hda1, make certain that you set the bootable flag for it; otherwise, Windows or DOS will not boot.

If you find that you have made an error somewhere along the way, just use the qcommand to quit fdiskwithout saving any changes and start over. If you don't specifically tell fdiskto write to the partition table, no changes are actually made to it.

When the partition table information shown on your screen matches your printed version, write the changes to the disk with the wcommand; you will be automatically exited from fdisk.Restart fdiskto verify your handiwork, and then remove the rescue disc and reboot.

It helps to practice manually restoring the partition table on an old drive before you have to do it in an emergency situation.

Booting the System from the Rescue Disc

For advanced Linux users, you can use the rescue disc to boot the system if the boot loader code on your computer is damaged or incorrect. To use the Rescue DVD to boot your system from /dev/hda1, for example, first boot the disc and press the F1 key. At the LILO prompt, enter something similar to this example. Note that you are simply telling the boot loader what your root partition is.

boot: linux rescue root=/dev/hda1

Using the Recovery Facility from the Installation Disc

Rescue mode runs a version of Fedora from the DVD that is independent of your system and permits you to mount your root partition for maintenance. This alternative is useful when your root partition is no longer bootable because something has gone wrong. Fedora is constantly improving the features of the Recovery Facility.

On beginning the rescue mode, you get your choice of language and keyboard layouts. You are given an opportunity to configure networking in rescue mode and are presented with a nice ncurses-basedform to fill in the information. The application attempts to find your existing partitions and offers you a choice of mounting them read-write, read only (always a wise choice the first time), or skip any mounting and drop to a command prompt. With multiple partitions, you must then indicate which is the root partition. That partition is then mounted at /mnt/sysimage. When you are finally presented with a command prompt, it is then possible to make your system the root file system with the following:

# chroot /mnt/sysimage

To get back to the rescue file system, type exit at the prompt. To reboot, type exit at the rescue system's prompt.

The rescue function does offer support for software RAID arrays (RAID 0, 1, and 5), as well as IDE or SCSI partitions formatted as ext2/3. After the recovery facility asks for input if it is unsure how to proceed, you eventually arrive at a command shell as root; there is no login or password. Depending on your configuration, you might or might not see prompts for additional information. If you get lost or confused, you can always reboot. (It helps to practice the use of the rescue mode.)

In rescue mode, a number of command-line tools are available for you, but no GUI tools are provided. For networking, you have the ifconfig, route, rcp, rlogin, rsh, and ftpcommands. For archiving (and restoring archives), gzip, gunzip, dd, zcat,and md5sumcommands are there. As for editors, vi is emulated by BusyBox, and pico, jmacs, and joeare provided by the joeeditor. There are other useful system commands. A closer look at these commands reveals that they are all links to a program called BusyBox (home page at http://www.busybox.net/).

BusyBox provides a reasonably complete POSIX environment for any small or embedded system. The utilities in BusyBox generally have fewer options than their full-featured GNU cousins; however, the included options "provide the expected functionality and behave very much like their GNU counterparts." This means that you should test the rescue mode first to see whether it can restore your data and check which options are available to you because the BusyBox version will behave slightly differently than the full GNU version. (Some options are missing; some options do not work quite the same — you need to know whether this will affect you before you are in an emergency situation.)

There are a few useful tricks to know when using rescue mode. If your system is functional, you can use the chrootcommand to change the root file system from the CD to your system in this manner:

# chroot /mnt/sysimage

You will find yourself at a new command prompt with all your old files in — you hope — the right place. Your familiar tools — if intact — should be available to you. To exit the chrooted environment, use the exitcommand to return to the rescue system prompt. If you use the exitcommand again, the system reboots.

The rescue environment provides a nice set of networking commands and network-enabled tools such as scp, sftp, and some of the rtools.It also provides rpm, which can fetch packages over a network connection. Installing them is tricky because you want them installed in the file system mounted at /mnt/sysimage, not at /. To accomplish that, use the --rootargument to set an alternative path to root:

Читать дальше

![Andrew Radford - Linguistics An Introduction [Second Edition]](/books/397851/andrew-radford-linguistics-an-introduction-second-thumb.webp)