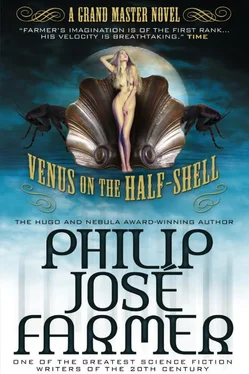

Philip Farmer - Venus on the Half-Shell

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Farmer - Venus on the Half-Shell» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Titan Books, Жанр: Юмористическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Venus on the Half-Shell

- Автор:

- Издательство:Titan Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1781163061

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Venus on the Half-Shell: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Venus on the Half-Shell»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Now Simon must chart a 3,000-year course to the most distant corners of the multiverse, to seek out the answers to the questions no one can seem to answer. “Fun to read, and very interesting from the perspective of the history of science fiction.”

—

Venus on the Half-Shell — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Venus on the Half-Shell», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What if Farmer is a guest on that house-boat right now? What if he has managed to get hold of some writing materials? What if he’s saying to himself, “Hey, Charon, let’s do a collaboration! Why don’t we write a story pretending to be Trout; maybe a story about what happens when Jonathan Swift Somers III dies and wakes up on the banks of a million-mile-long river!”

That’s my worry. Or my hope. I’m not sure which.

AFTERWORD

MORE REAL THAN LIFE ITSELF: PHILIP JOSÉ FARMER’S FICTIONAL-AUTHOR PERIOD

BY CHRISTOPHER PAUL CAREY

“The unconscious is the true democracy. All things, all people, are equal.”

PHILIP JOSÉ FARMERBy one count, Philip José Farmer, a Grand Master of Science Fiction, has written and had published fifty-four novels and one hundred and twenty-nine novellas, novelettes, and short stories. Creatively, Farmer’s work is equally ambitious. In 1952, he authored the groundbreaking “The Lovers,” which at long last made it possible for science fiction to deal with sex in a mature manner. He is the creator of Riverworld, arguably one of the grandest experiments in science fiction literature. His World of Tiers series, which combines rip-roaring adventure with pocket universes full of mythic archetypes, is said to have inspired Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber series and is often cited as a favorite among Farmer’s fans. And in the early 1970s, he penned the authorized biographies of Tarzan and Doc Savage and inspired generations of creative mythographers to explore and expand upon his Wold Newton mythos. Yet among all of these shining minarets of his opus, Farmer has stated that he has never had so much fun in all his life as when he wrote Venus on the Half-Shell.

I believe it is no coincidence that this novel belongs to what Farmer has labeled his “fictional-author” series. A fictional-author story is, as defined by Farmer, “a tale supposedly written by an author who is a character in fiction.” Many of Farmer’s readers are aware that Venus on the Half-Shell originally appeared in print as if authored by Kurt Vonnegut’s character Kilgore Trout. However, most are not aware that Farmer, in league with several of his writer peers and at least one major magazine editor, masterminded an expansive hoax on the science fiction readership that spanned a good portion of the 1970s.

As with Farmer’s usual modus operandi, the plan was ambitious. Beginning in about 1973-74, in true postmodern reflexivity, a whole team of writers acting under Farmer’s direction were to begin submitting fictional-author tales to the short fiction markets. Farmer’s files, to which the author kindly gave me access, reveal that his plan of attack was executed with focus, precision, and a great deal of forethought.

The authors queried to write the fictional-author stories were instructed that “the real author is to be nowhere mentioned; it’s all done straight-facedly.” Each story would be accompanied by a short biographical preface giving the impression that the fictional author was indeed a living person. However, all copyrights were to be honored; those who chose to write stories “by” the characters of other authors would need to contact those creators for permission. Sometimes Farmer himself wrote the creator and, having received permission, then handed over the fictional-author story to his fellow conspirator to complete. Authors were encouraged to submit their stories to whatever market they pleased, although the majority were to appear in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction , whose editor, Edward L. Ferman, was in on the joke. Once enough of the stories had been published in various markets, Farmer himself planned to take on the role of editor and collect them all in a fictional-author anthology.

Writing even before the fallout with Kurt Vonnegut (which is described in great detail by Farmer in his “Why and How I Became Kilgore Trout”), Farmer placed great emphasis on literary ethics during the execution of his hoax. Even authors whose characters had lapsed into the public domain—and whom Farmer and his cohorts could have used legally without payment of royalties—were offered 50% of any monies made by the publication of a fictional-author story (a stipulation that appears to have been waived by all of those who granted Farmer permission). Provisions were made for the original authors and their agents to receive copies of the stories upon publication. And always, Farmer made clear that his request to write a story under the name of an author’s character was his intimate tribute to said author.

While the vast majority of those queried for the use of their characters granted permission, a couple did not. Farmer wrote respectful, though clearly disappointed, replies to these authors, explaining again that he only meant to honor them with the stories, but that in deference to them he would withdraw his offers and pursue them no further. Most authors, however, reacted much differently and became infected by the passion that seemed to ooze from Farmer when he proposed to them his audacious hoax. Nero Wolfe author Rex Stout, besides granting permission to write the story “The Volcano” under the name of his character Paul Chapin, was tickled enough to suggest that Farmer should also author stories by Anna Karenina and Don Quixote. Farmer’s correspondence indicates that he planned on doing just that. P. G. Wodehouse, author of the Jeeves and Blandings Castle stories, also tried to come up with alternative fictional-authors among his own works that could be used, and it is telling of the excitement surrounding Farmer’s fictional-author conceit that multiple authors queried for permission enthusiastically consented by exclaiming the phrase “Of course” within the first paragraph of their replies. Occasionally, permissions went in the other direction. J. T. Edson, the author of many Westerns, sought permission to use Farmer’s Wold Newton genealogy as the basis for his own characters’ ancestry in his Bunduki series, a request Farmer happily approved; and while the Wold Newton genealogy was not exclusively related to the proposed fictional-author series, it remains clear that Farmer was pleased to interweave the two concepts in several instances.

As concerns those peers enlisted to write the fictional-author stories under Farmer’s coordination, the list included (among others) Arthur Jean Cox, Philip K. Dick, Leslie Fiedler, Ron Goulart, and Gene Wolfe. Unfortunately, not all of these writers succeeded in completing their stories or having them published, though there were some notable exceptions. At Farmer’s suggestion, Arthur Jean Cox tackled one of his own creations, writing “Writers of the Purple Page” by John Thames Rokesmith, published in the May 1977 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Rokesmith was a character in Cox’s novella “Straight Shooters Always Win” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction , ed. Edward L. Ferman, May 1974). And Gene Wolfe—whose humorous “Tarzan of the Grapes” appears in Farmer’s survey of feral humans in literature, Mother Was A Lovely Beast —wrote “‘Our Neighbour’ by David Copperfield,” first published in the anthology Rooms of Paradise (ed. Lee Harding, Quartet Books, 1978), albeit under Wolfe’s own name. But the fun did not end there. Author Howard Waldrop, although not enlisted by Farmer, sought out the author of Venus on the Half-Shell and joined in with the other conspirators, publishing “The Adventure of the Grinder’s Whistle” as by Sir Edward Malone in the semipro fanzine Chacal #2 (eds. Arnie Fenner and Pat Cadigan, Spring 1977; reprinted in the collection Night of the Cooters , Ace Books, 1993, wherein Waldrop, in his introduction to the story, says, “Like with most things from the Seventies, this was Philip José Farmer’s fault”). Harlan Ellison’s “The New York Review of Bird” (Weird Heroes, Volume Two, ed. Byron Preiss, Pyramid Books, 1975), while not technically a fictional-author story, was tied in with Farmer’s project, and served to turn Ellison’s nom de plume, Cordwainer Bird, into a full-fledged fictional author. Bird went on to appear in Farmer’s fictional-author tale “The Doge Whose Barque Was Worse Than His Bight” as by Jonathan Swift Somers III (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Edward L. Ferman, November 1976; reprinted in Tales of the Wold Newton Universe , Titan Books, 2013). Farmer himself used the Cordwainer Bird pseudonym for his story “The Impotency of Bad Karma” (Popular Culture, ed. Brad Lang, First Preview Edition, June 1977), which he later revised and had published, using his own name this time, under the title “The Last Rise of Nick Adams” ( Chrysalis, Volume Two, ed. Roy Torgeson, Zebra Books, 1978), and integrated Bird into his Wold Newton genealogy in Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life (Doubleday, 1973; reprinted in a deluxe hardcover edition by Meteor House, 2013, and in paperback and ebook editions by Altus Press, 2013).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Venus on the Half-Shell»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Venus on the Half-Shell» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Venus on the Half-Shell» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.