There was also speculation that Isaac Asimov might be the mysterious “real” author of the book, or perhaps it was John Sladek, another trickster, who had already conceived I-Click-as-I-Move, a robot version of Asimov, who was pretending to be Asimov pretending to be Trout. My own view is that T.J. Bass should have been nominated too and it’s fishy that he wasn’t.

Things settled down until the August 11 issue of Locus where they reported a rumor that Philip José Farmer was Kilgore Trout. This was followed by notices in the September 12 issue where Farmer denied being Trout and another letter by Trout appeared where he said he was flattered that all of these authors were rumored to be him, but that “there must be some way to assert my existence as a real person.” He couldn’t think of a way, though, and neither can I, offhand, and that’s because he wasn’t a real person. So really he was being duplicitous. Or rather, Farmer was being duplicitous on his behalf, which was generous of him really, if you stop to think about it.

But this was just the beginning of the japery. Farmer was an expert trickster at the center of his warm heart, and he couldn’t wait until the publication of the novel to begin having some serious fun. The November 1974 issue of the SFWA (Science Fiction Writers of America) Forum contained a long and very badly written, badly sppellled, and even worsely punct-uated letter from Kilgore Trout asking for an application so he might join, and also saying that he was looking for a place to live. The letter concluded, “…if you need character references write david harris of dell. dont write to mr vonnegut. he never answers his mail.”

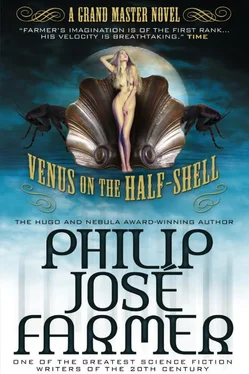

Shortly afterwards, an incident occurred that almost stopped the project before it began. On December 1, 1974 well-known literary critic Leslie Fiedler was on the PBS television program Firing Line, hosted by William F. Buckley. They were speaking of science fiction and both Kurt Vonnegut and Kilgore Trout’s names came up. Fiedler, who was a friend of Farmer’s and knew all about Venus on the Half-Shell, said, without naming Farmer: “What he did is he just wrote a book by Kilgore Trout… Vonnegut didn’t want him to do it, but he said, ‘I’ll go to court and get my name officially changed to Kilgore Trout, and you can’t stop me.’” Vonnegut was angered and withdrew permission for Farmer to write any more novels “by” Kilgore Trout.

Prior to the novel’s publication in paperback, it was abridged and serialized over two issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (December 1974 and January 1975). It was the feature story of the December issue, getting not just top billing, but cover art as well. So it can be rightly said that this was the place and circumstance of my birth, where the world first discovered that Simon Wagstaff—the protagonist of Kilgore Trout’s first work to be published outside of a nudie magazine— had a favorite science fiction author. Me.

Excuse me while I stop for a moment to catch my breath. It always fills me with a strange feeling when I stop to consider that I’m not a living human being, that my father was an author and my mother a magazine. Well, perhaps some of your fathers were authors too, but I bet they didn’t write you into existence, did they? I bet they created you some other way. OK, I’m fine now. Let’s move on.

In the same way that Vonnegut would have his characters describe stories written by Kilgore Trout, Trout, I mean Farmer, did the same with me. Simon Wagstaff, the protagonist of the novel, would tell his companions about stories I had written. And let’s face it, telling readers about fictional stories that haven’t really been written is a shortcut method of laying claim to the ideas in those stories without having to go through the exhausting process of actually writing them. So Trout saved himself a lot of valuable time, and the saving was passed on to Farmer. And we have no choice but to assume Trout passed all that saved time on.

So the stories I, Jonathan Swift Somers III, had written could be summarized even though they didn’t exist; but they could only be summarized if the pretence was maintained that they did exist. Otherwise, they would just be pitches, not proper summaries, and pitching stories is less satisfying than summarizing them, even if they are identical. Does that make sense?

In a similar vein, the Polish science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem once published a volume of literary reviews of books that didn’t exist. He did this because he didn’t have time to write the actual books but he wanted to lay claim to the original ideas they contained. Some critics feel this is a lazy approach but I believe it’s ingenious and I only wish that Lem had reviewed my own books. However, Farmer seems to have had more energy than Lem, more energy than one might deem possible, for he was willing not only to imagine and summarize stories that didn’t exist in order to save time; he was willing to later spend that same time writing those stories to match and even exceed the summaries! And let me add that Farmer once reviewed one of Lem’s books, Imaginary Magnitude, a collection of introductions to books that don’t exist. Squeeze my Lem ’til the juice run down my leg!

But to return to the way that I was presented in the Venus novel… In the first instance, the story described (that is, the story I had written) was of less importance in the text of the framing novel and Farmer spent more time describing me. Apparently he didn’t want anyone to have to come along behind him and fill in the details of my life story, as he had to do with Trout. The other stories of mine, however, were more detailed in their summary and were revealing about two of “my” creations. First, there was Ralph von Wau Wau, a genetically enhanced German Shepherd with a 200 IQ and the ability to speak. Farmer states that with the exception of Ralph, all of my protagonists have major disabilities, this being due to my own condition of being paralyzed from the waist down. The second of my characters described is John Clayter, a space traveler whose spacesuit is full of (often malfunctioning) prosthetics.

If a fictional character invents another fictional character who invents another fictional character who invents another fictional character, is there a grading of existability (for want of a better word)? I mean… is a dream within a dream less real than the dream that frames it, or are they both equal in terms of the fact that neither have concrete form? This is a question that has understandably intrigued me for quite some time. If you know the answer, please keep it to yourself, okay? I’m freaked out enough by my condition already.

Anyway, the Dell paperback edition of Venus on the Half-Shell came out in February 1975 (available for the first time without lurid covers!) and the reviews, and controversy, quickly followed. Funny how that happens, isn’t it? Do you imagine, as I do, the book traipsing down the street, followed by a number of reviews that are stumbling to keep up, with controversy close behind, its nose in the rear end of the last review in line? That’s the picture I see in my mind, anyway…

A wildly popular fanzine, Richard Geis’ Science Fiction Review, ran a review of Venus on the Half-Shell in the February 1975 issue. The humorous novel was full of clichés as Farmer poked fun at the genre; after all, he had written the novel he believed Kilgore Trout, a science fiction hack, would have written had Trout existed. Since Vonnegut had for years taken umbrage at being labeled a science fiction writer, and since Richard Geis assumed Vonnegut had in fact written the book, Geis took offense at a novel that seemed to make fun of, and look down on, science fiction because he did not feel that Vonnegut had earned the right to do so (a case of, it’s okay for me to call my sister ugly, but if you do it, I’ll punch you in the nose). Geis’ review wasn’t very gentle. In fact, it came out swinging.

Читать дальше