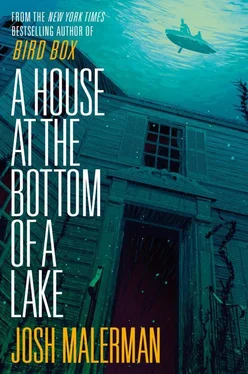

Джош Малерман - A House at the Bottom of a Lake

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джош Малерман - A House at the Bottom of a Lake» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2021, ISBN: 2021, Издательство: Del Rey, Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A House at the Bottom of a Lake

- Автор:

- Издательство:Del Rey

- Жанр:

- Год:2021

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-59323-777-9

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A House at the Bottom of a Lake: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A House at the Bottom of a Lake»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A House at the Bottom of a Lake — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A House at the Bottom of a Lake», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Some how.

The beaver’s wide eyes seemed to stare up into the light.

James ran a finger along its back, over the holes.

He gripped it between his forefinger and thumb.

How.

He tugged.

For a beat it felt like it was going to come up with his hand. James could see the teeth, the eyes, the flat tail rising from the counter like any rational object should.

But it didn’t move at all.

James’s vision wasn’t the best through the mask but it was good enough. Floating above the kitchen floor, he bent at the waist and examined where the shaker met the counter.

Being in the business of adhesives and tools, James had seen a hundred broken objects. He’d be able to spot a fix from across the kitchen. But there was no sign of glue at the base of the beaver.

James looked to the exit, to where he’d last seen Amelia swimming. For a breath he thought he saw her, arms crossed, eyes alight, no mask, no tank, no suit, watching him from across the kitchen.

He felt some shame for doing what he was doing.

He pulled on the shaker again. Harder this time.

No give.

No wiggle.

The shaker did not move.

James pulled a pocketknife from the small pouch secured around his waist. He popped it open. Holding the light with one hand, he wedged the knife where the shaker met the counter. He dug at it.

His flippers rose up behind him as he worked, until he was floating horizontal to the counter, his mask only a few inches from the beaver’s teeth.

He dug at it again.

No wiggle.

No give.

James put the knife back in the pouch and swiveled toward the bigger knives. Their handles jutted out of their wooden holder.

He thought of Amelia. What she would say.

Why’d you need to know? This place is ours, James. Isn’t that enough?

He looked back to the shaker, thinking maybe he should leave it alone.

But the shaker wasn’t on the counter anymore.

“What?”

The porcelain animal floated, eye level, and James watched it rotate in place, as if someone were turning it, showing him the bottom, showing him there was no evidence of glue.

James reached for it.

The shaker floated up, toward the ceiling.

James reached for it again and again it spun away.

He shone the beam in the space surrounding the shaker.

A pocket of cold water rolled the length of his body. James knew the feeling well. He’d experienced it in flooded basements, helping his dad repair a neighbor’s pipes. Water so cold it seemed to grip you with actual fingers.

James sensed life behind him and turned quick.

A distorted face was inches from his own.

He yelled into his mask.

But it was Amelia.

Only Amelia.

Only.

She placed a hand on his shoulder. She was smiling.

She motioned for him to follow her. She was mouthing words. A door, she seemed to be saying. A new door. James held up a finger, telling her to hang on, he had something to show her, too.

But when he shone the light to where the shaker had been, it was back, secure, on the counter.

The big teeth and dumb eyes glinted in his trembling beam.

Come on, Amelia seemed to be saying. You’re gonna love this.

She swam from the kitchen and James followed.

23

While James was in the kitchen, studying the pepper shaker, Amelia had been doing flips, floating somersaults, through every room in the house. By the time she reached the lounge with the oil painting still life, she was dizzy from it, even a little turned around. She flipped once more and her flippers struck the wall and the wall opened and Amelia gasped, within her mask, understanding that, despite having explored the house a dozen times now, there were still new rooms to be found.

She swam into the surprise entrance and excitedly ran her beam in all directions, finding at first only a wall of chipped pink paint, possibly a closet. She shone the light to the floor, expecting (and hoping) to find shoes, evidence of someone having once lived here, like the floating dresses in the room upstairs.

But there were no shoes.

There were stairs.

Amelia treaded for half a minute, the word basement playing in her mind. The word impossible, too, as the house ( our house ) was situated firmly in the muddy muck of the very bottom of the lake.

Finally, she swam toward the stairs, head down, her flippers clipping a lightbulb’s string above. But before fully diving into the subterranean level of the house, she stopped.

James.

She found him in the kitchen looking as if he’d seen a flesh-and-blood chef crawl into the oven and close the door. She convinced him to follow her.

Minutes later, treading above the staircase that, an hour before, neither of them had known existed, James thought the same two words Amelia had.

Basement.

Impossible.

But a third word worried him most.

Trapped.

As if, by swimming below, they wouldn’t have only the lake above them.

They’d have the house, too.

Amelia swam first, head down. He watched her flippers vanish beyond the reach of his beam, into the throat of the stairwell.

Then he followed.

24

There were thirty steps in all. The stairwell was a tunnel of its own, traveling down at a dizzying angle. And like the concrete tunnel that delivered them to the third lake, there was graffiti.

Of a sort.

Rather than crude drawings of penises and naked women, the writing read like a growth chart, though neither James nor Amelia could fully envision a parent asking their child to stand against the wall, halfway down the basement stairs, in order to mark their height.

But there were marks. Rising marks. As if somebody’s development had been noted.

After examining the marks for a minute, James and Amelia continued down.

Deeper.

At last, they arrived at an entrance to a wide room and Amelia felt another lightbulb string trace her spine as she passed under it. She had to swim lower to avoid wooden support beams, the foundation of the home. She spotted a web, a large one, where one of the beams met the ceiling, and paused to show James. They treaded near it, studying the intricate design rippling with waves that must have come down the stairs with them.

A spider’s web. Underwater. In a house at the bottom of a lake.

They continued, deeper, into the basement.

Space, James thought. The room had a lot of space. Amelia tugged on his wet suit and pointed down with her beam, showing him a familiar flooring below. Blue-and-white tiles labeled with measurements, 3 ft., 5 ft., that in another context surely would have been clear but down here simply could not be.

And yet as that which could not be was in this house, the basement proved no different.

Amelia and James treaded water six feet above an indoor pool.

With water all its own.

The surface moved independently of the water they swam in.

Amelia laughed and James could hear it, muffled by her mask, coming to him in marveled beats that perfectly embodied the wonder she was relishing.

Then she dove, swimming headfirst into the pool.

25

It’s warmer, Amelia thought. Warmer like an indoor pool ought to be. Like when somebody says it’s bathwater. Bathwater, Amelia thought, soothing and smooth, enveloping, tomblike, like a womb.

She rolled onto her back and sank to the concrete bottom. The tank struck first and she looked up through her mask, through the independent surface of the pool, into the lake water that held James, suspended so high above her.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A House at the Bottom of a Lake»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A House at the Bottom of a Lake» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A House at the Bottom of a Lake» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Джош Малерман - Мэлори [litres]](/books/388628/dzhosh-malerman-melori-litres-thumb.webp)