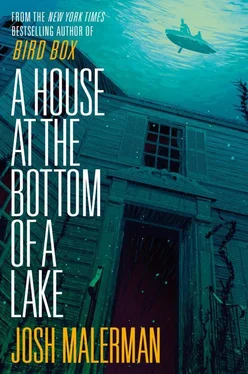

Джош Малерман - A House at the Bottom of a Lake

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джош Малерман - A House at the Bottom of a Lake» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2021, ISBN: 2021, Издательство: Del Rey, Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A House at the Bottom of a Lake

- Автор:

- Издательство:Del Rey

- Жанр:

- Год:2021

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-59323-777-9

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A House at the Bottom of a Lake: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A House at the Bottom of a Lake»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A House at the Bottom of a Lake — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A House at the Bottom of a Lake», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It worked.

Free, he looked into the mirror as he passed it, smiling behind the glass helmet.

It was the visage, James thought, of young love.

He saw a room ahead, piecemeal, made up of the brief patches of light he afforded it. It was a dining room. The table and chairs told him that. But nothing told him how the table and chairs remained fixed as they were to the floor.

Nor did anything explain the rug beneath the legs of the chairs. Or the hundreds of trinkets that lined the shelves of a glass cabinet against the right wall.

No hows, James thought. No whys.

It was impossible not to feel like he’d broken into this home. If not for the darkness, the distortion, and the cold, James would have counted himself lucky for not having run into whoever owned it.

He moon-stepped toward the dining room and got snagged again.

“Dammit.”

He turned and sent another ripple through the tube. It traveled the length of the hose, slow motion, vanishing through the dark rectangle of the half front door into the muddy front yard beyond.

Then, the ripple came back.

Toward him.

As if James were outside the house and the hose were here, snagged where he stood.

James trained the flashlight on the front door, tracing the rectangular door frame. Mud motes and minnows passed through his light, then vanished fast into the darkness.

He waited for a second tug from outside of the house. Another ripple.

You’re breathing too hard, man.

But that wasn’t possible. Unless someone sent it his way.

He thought of Amelia up top.

Had she sent him the wave in the breathing tube? She must have. But was she trying to tell him something?

Someone’s up there, he thought. Someone telling her to get her boyfriend out of the water and get home. NOW.

James lumbered back to the front door. Peering over the threshold, he saw that the tube was indeed snagged on one of the porch handrails.

He took the hose between a gloved finger and thumb.

Did you just call yourself her boyfriend?

The hose came loose from the handrail and James easily coiled the slack. He reentered the house.

He wanted to go deeper this time. Deeper into the house. Deeper into the lake.

Deeper in love.

Is this love? Is that happening?

He got to the dining room quickly, more agile than he was moments ago. And despite the darkness ahead, the darkness everywhere, he felt safe.

Alive.

He floated to the dining room table.

The flashlight showed him a tablecloth, serving dishes, folded napkins, and eight high-backed chairs. A chandelier hung from the ceiling, swaying gently with the unseen waves alive here at the bottom of the lake.

There were paintings on the walls. Landscapes that seemed to undulate, as if something lived beneath the yellow grass.

How?

Unlit candles. Sconces. Utensils. All of it sedentary on the table. On shelves. On plates.

How?

A solid wood buffet. A tray upon it. Not floating. Not moving at all.

HOW?

“No hows, ” James said into the helmet. “No whys. ”

Amelia was far above him. Watching the compressor.

James went deeper.

The hose followed smoothly. The hose did not get snagged.

And James went deeper into the house.

15

Past the dining room, a study. One wall lined with books.

Intact. Bound. Underwater.

Books.

James trained the flashlight on the titles. Foreign languages, or maybe the letters had been ruined by water after all, stolen a piece at a time, the three lines that made up an A, the three of an F. By the bookshelf was a chair, solidly planted on the ground, beside it an end table with an ashtray, beyond it a bay window. By James’s light, the world outside the glass was pitch-black, yet he could see something out there. Seaweed waving at the base of the window, mud floating on submerged waves, the pulse of the lake.

James sat down in the study chair. Put his gloved hands on the armrests.

He noted the wallpaper, tiny ducks fleeing a shadow-faced hunter.

A stepladder to reach the higher books.

A second door, behind the study chair.

James grew colder. Physically, yes, but in a fearful way, too. Scary thought, himself seated in the study of an impossible home at the bottom of a lake. It suddenly felt possible, no, likely, that something dead could come floating through the door he’d entered by. Something falling to pieces, pulling apart, coming toward him, consciously or not, a drifting once-was, unglued.

He tried to pick up the ashtray on the end table. It wouldn’t move.

James stared at it for a long time, resisting the word why.

He got up and adjusted the tube’s slack, giving him another twenty feet of walking room.

Astronautlike, he rounded the chair and opened the second door. Because he didn’t have the flashlight lifted yet, wasn’t pointing it ahead, he saw nothing. In that moment, that single drumbeat of absolute darkness, he felt as if he were stepping into the nothingness of death, a real end, a place where he’d never be able to find Amelia, never find warmth, solace, confidence, triumph, reason, or love ever again.

Don’t enter this room.

A dark thought to have at a dark threshold.

But James entered the room.

He brought the flashlight up and yelled, two involuntary syllables crashing against the helmet’s glass.

A pale face in the flashlight. Staring into his eyes.

James stepped back, knocking his elbow against the wall.

But it was only a painting.

“Jesus,” James said. Then he laughed at himself. And he wished Amelia had been here to hear him scream.

Not a face. Not eyes after all. Two plums on a white table, the edge of the table like a perfectly set, unsmiling mouth.

A rippling still life beneath the ( roof ) waves.

James leaned toward the painting, bringing the helmet’s glass half an inch from the canvas. He thought it was an oil painting. He recalled the cliché like oil and water. He wondered if that had something to do with why it was still intact.

He shone the flashlight around the room, getting details the way he got anything in this house: in pieces. As if a puzzle had been dropped into the third lake many years ago, and now James and Amelia were here to put it back together again.

A brown leather couch. A long, thin window. Cabinet doors. A coffee table. A rug.

“A rug,” James said. He knelt to the ground and ran a glove over the hundreds of tiny tendrils, red and white fabric sea anemones.

It occurred to James that he was in a nice house. The nicest he’d ever been in.

He rose and turned and saw a pool table. The balls were racked at one end. The cue waited at the other.

Play me, it seemed to say. But don’t ask how.

James gripped a stick from a wall mount. Then he paused.

Staring into the space beyond the other end of the table, it felt like someone could be there. Someone to play a game with. As if, were he to break the balls, unseen fingers might take the stick from him, might go next.

He set the cue back into the mount. Then, taking the breathing tube’s slack up by his hip, he exited the lounge.

He stepped into a new room, but before he could determine what sort it was, his flashlight died.

Darkness.

Alone with it.

Clumsily, through the ape gloves, James clicked the flashlight’s switch on/off, on/off. He shook it, then cracked it against his hip. The suit was too bulky there so he tried it against his other arm. Too bulky there, too. He raised it up to his helmet, brought the dead flashlight back, and… stopped.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A House at the Bottom of a Lake»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A House at the Bottom of a Lake» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A House at the Bottom of a Lake» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Джош Малерман - Мэлори [litres]](/books/388628/dzhosh-malerman-melori-litres-thumb.webp)