“Good morning,” called Susan, waving brightly as she came down the stairs.

“Hello, hello.” Andrea squinted over the tops of the glasses. “Where’s the family? Did they leave you and find some other mother?”

“No. They’re out and about,” said Susan, thinking, strange joke . “I’m on the way to meet them for lunch.” She stopped at the bottom of the steps and turned to stand next to Andrea. “Whatcha looking at?”

“Oh, nothing. Nothing, really.”

Andrea slipped one old, sticklike arm through the crook of Susan’s arm and leaned her head against her shoulder, like they were best friends, or mother and daughter. The gesture, so intimate and unexpected, flustered Susan, but she recovered and brought her other hand across her midsection to pat Andrea on the forearm. Susan’s mother had been struck and killed by a drunk driver, two years after Susan’s college graduation. She had been on a hostel-hopping painting tour of Europe, having the time of her life, when she got the telephone call. She had cried for seven hours on a plane from Paris and signed up to take the LSAT three days after the funeral.

“I hope the apartment is OK,” said Andrea throatily, then coughed twice and turned her face toward Susan’s. “Is the apartment OK?”

There was a deep-set, unsettled melancholy under the growl in Andrea’s voice, and a sort of confusion. For the first time Susan wondered if Andrea, for all her seeming vigor and spiritedness, wasn’t beginning to slip into senility. The arm still linked in Susan’s was old but it was sturdy, yellow and clustered with age spots. Halfway up the forearm was a small open sore, red and bright and glistening in the sun.

“The apartment is just fine, Andrea. Thank you. We love it.”

“There’s nothing I can do to make it better for you?” Andrea lifted her sunglasses and searched Susan’s face. “I want so much for you and your family to be happy here.”

It occurred to Susan that Andrea wanted her to throw out a couple of problems that she could solve, that her elderly landlady somehow craved the reassurance of being responsible for someone else’s welfare. “She seems … oh, just sad, I guess,” Louis had said. “The house has a whole lot of sadness in it.”

“Well, OK,” said Susan. “Actually, there are a couple of, you know, just a couple of little things.” Quickly she ran down the short list of minor problems they’d discovered since moving in last week: the broken floorboard on the upstairs landing; the cracking paint in the downstairs bathroom; the loose outlet cover in the kitchen.

“Those aren’t little things, Suze,” said Andrea. “Not at all.”

Suze? The nickname made Susan’s skin crawl, but she said nothing. Andrea at last pulled her arm free from Susan’s, the wrinkles around her eyes and on her forehead multiplying as she furrowed her brow. “It’s an old house, as I told you. As I warned you, really. But of course, of course , I will get Louis to take a look at everything, just as soon as he can.”

“Thanks.” Susan paused, bit her lip. “I feel like there was one more thing.”

“Yes?”

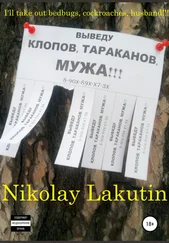

The word scurried across her throat again, nearly slipped out onto her tongue: bedbugs. Bedbugs. Tell her about the—

But of course she had decided there were no bedbugs — hadn’t she? — and she could hardly complain to the landlady about a spot of dirt on her pillowcase. “Oh, right, I know. There’s been this kind of noise. Like a …” She gestured vaguely with her hands. “Like a ping , kind of.”

“A ping ?” Andrea narrowed her eyes. She was now standing with one foot on the bottom step, and Susan noticed that she had come outside wearing a pair of thin-soled lime green slippers. “Where is it coming from?”

“Well, that’s what’s weird,” Susan said, a little embarrassed even to have brought it up. “I’m not exactly sure. We’ve just sort of heard it, generally. Mostly in the living room area, I guess. It’s extremely faint, and it never lasts for very long. Not a big deal, really.”

“Don’t worry,” said Andrea. “I’ll take care of it myself.”

Somewhere out over the East River the sun drifted behind a bank of gray clouds, and 56 Cranberry Street was momentarily cast in shadow, silhouetted like a black crepe cutout hung on the backdrop of sky. It was almost noon, time for Susan to be at Theresa’s with her man and child, eating a tuna sandwich and hearing funny stories about ballet class. As if sensing her impatience, Andrea abruptly began to hike up the stoop.

“Anyway, Suze,” she said. “We’ll speak another time.” As Susan watched, Andrea pulled the big red door closed behind her.

The rest of the weekend unspooled in a series of happy, easy hours. After lunch on Montague Street, Susan, Alex, and Emma strolled the tree-lined streets, exploring their new neighborhood as a family. They stopped at the drugstore, at the bank, and at Area Toys to buy Emma a jigsaw puzzle. At the farmer’s market on Cadman Plaza they bought a bag of ripe Honeycrisp apples, a thing of frozen sausage, and three bundles of asparagus. After nap, Susan and Emma did the jigsaw puzzle, Susan marveling as her precocious genius-child patiently sorted through the twenty-four oversized pieces to assemble the barnyard scene.

“I take it all back,” Alex said that night as he fried the asparagus with olive oil and salt. “This kitchen is actually terrific.” He winked at Susan and she winked back. When Emma was asleep they polished off a bottle of Prosecco and made love on the living room floor — their first time since moving to Brooklyn.

Sunday morning Susan walked over to the Laundromat with a load of whites, leafed through the Times magazine until the buzzer buzzed, and then switched the stuff over to the dryer. When she caught up with Alex and Emma at the playground, she smiled to see that they’d met up once again with Shawn, and that Shawn had a seven-year-old sister named Tarika, with a pair of braided pigtails and a gap-toothed smile. The two families ended up having lunch at the Park Diner, and by dessert Emma was head over heels for Tarika, trailing the girl faithfully to the cookie case and hanging on her every word like revelation.

“Oh, shoot,” Susan said suddenly, hours later, as Alex and Susan lay in bed reading.

“Shoot what, gorgeous?”

“I gotta go back to the Laundromat. Our stuff is still sitting in the dryer.”

“No way, dude.” Alex tossed his New Yorker on the ground. “I’ll grab it.”

“You sure?”

“Am I sure?” He grinned and hopped out of bed. Susan smiled, feeling safe and sleepy. “What are husbands for?”

Alex tugged on his blue track pants, planted a loud kiss on her forehead, and was gone. For once, Susan drifted off easily and was still sleeping soundly twenty minutes later, when Alex came home, folded the laundry, and put it all away — including the pillowcase that had borne the small and curious stain.

On Monday morning at 9:13, Susan stepped into the bonus room, cried out, and dropped her coffee cup. The ceramic mug smashed to pieces on the hardwood, splashing Susan’s legs with scalding liquid where they peeked out from her pajama bottoms. She screamed again, in pain and surprise, stumbled backward and clutched the doorframe, but her eyes remained locked on the portrait. Though still half complete, it was nevertheless an excellent rendering, a vivid and precise re-creation of the girl in the photograph that she’d stuck on the lower-right-hand corner of the easel. Sweet, funny Jessica Spender with her slash of scarlet bangs, her wicked and amused expression, her high cheekbones and red lipstick.

Читать дальше