And so the argument went:

“ When will you accept the fact that she’s going to die?” Jenna had asked a month earlier.

“I can’t stop trying,” Luke said.

“You’re making her miserable.”

“How would you know? You’re never home.”

“I’m working . I have a job .”

“I take care of Amy,” Luke said. “That’s my job.”

“Take care of her? All you do is drag her across the country, giving her false hope time after time after time.”

“You want me to throw in the towel like you?”

“I want you to accept the fact that our daughter is going to die. And damn it, Luke, let her die here, at home, with her family and friends. Someplace familiar. Not out there. Not in the middle of nowhere. Please, Luke.”

And so the argument went.

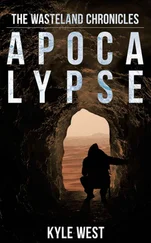

Now here, in the tunnel, Amy looked so small in Luke’s black leather jacket. “It smells like old books in here.”

Luke pulled a handkerchief from his pocket. Is it the mold? “Wrap this over your mouth and nose.”

“Geez, Dad.”

Luke stopped and listened, thinking he heard movement. He had no desire to run into anyone, especially not with his daughter here. But it was only the hollow echo of dripping water; the tunnel walls perspired with it, glistening in the weak beam of Luke’s flashlight. Bats clung like burnt lichens to the limestone.

“Can you please tell me what we’re doing here?”

Dim light ahead. Luke turned off his flashlight. Cool air chilled the sweat on his arms and neck. The tunnel stopped beneath a grate embedded in the limestone ceiling. Light spilled through the gaps between the bars.

“Dad?”

Luke wiped the sweat from his forehead. He surveyed the small area beneath the grate, finding a jagged ledge protruding from the tunnel wall. He motioned to it. “Here. Sit here.”

Amy rested her back against the hard rock. “I’m tired.”

“Close your eyes, honey. Try to sleep.” He dug a blanket from his backpack and placed it over his daughter. He sat next to her and put his arm around her shoulders, pulling her to him. He looked up at the grate, took a sip of bottled water, and waited.

But wouldn’t all the endless miles, the rest stops, the gas stations, the cheap motels be worth it if they found a cure? He knew there were charlatans out there, crooks taking advantage of desperate people like him for a quick buck. He wasn’t completely naïve. But maybe the doctors back home didn’t have all the answers, maybe there really were miracles out there waiting to be found. And besides, how could he live with himself if he didn’t at least try?

He’d scoured the internet, joined discussion boards, frequented chat rooms, grasping, groping for any piece of information out there, but it was like trying to build a bridge by tossing pebbles into the ocean.

One night, an email from a stranger; “Have you heard of Padre Sapo in Guanajuato?”

He didn’t even know where Guanajuato was. He looked it up on the Internet. Middle of Mexico . So far, he’d kept his search to the U.S. Couldn’t afford to globetrot. But Mexico — that was close enough, wasn’t it? And cheap?

He replied to the email, asking for more information, and received a brief message with an attached J-Peg. Padre Sapo , the caption said. Father Toad. A poor quality picture, but Luke made out a man standing on a platform of rock in a small amphitheater carved out of a mountain. An elderly woman kissed his chest, while a line of the afflicted waited their turn.

The email contained only an address and the brief message; “From his ugliness, I was cured. May he bless and heal your child.”

A burst of feedback woke Luke up. The light spilling through the grate had turned orange. He heard voices now, too, voices from the amphitheater above. He looked at Amy. She stared back at him, eyes wide, as if trying to figure out whether or not she was still dreaming. Luke ran his fingertips lightly over her cheek.

“It’s okay,” he whispered. “It’s just me.”

Recognition filled her eyes. She shivered. “How long was I out?”

He checked his watch in the dim orange light. “Little over an hour.”

Luke stood on the ledge and craned his neck trying to see past the iron bars of the grate. “Sounds like they’re getting ready.” He couldn’t see much, except for stage lights and the thin metal pole of a microphone stand.

Footsteps thudded above. Amy looked up. “Would you please tell me what’s going on?”

For a moment, Luke looked like a little boy caught playing with matches. He shrugged. “They call him Padre Sapo . Father Toad.”

“Father Toad?”

He smiled weakly. “They say his skin looks like that of a toad.”

Amy shivered. “Why are we waiting for him?”

“They say the moisture from his skin can heal anything.”

Amy stared. Shook her head. “Jesus, Dad. You’ve got to be kidding me.” She looked so tired, the shadows of the tunnel turning the dark circles beneath her eyes into a black paint.

“We’ve got to try,” Luke said. “We’ve got to try.”

When they’d first arrived in Guanajuato, they tracked down the address Luke received in the email. Amy waited in the pickup truck with the windows rolled down to let in the gentle breeze, while Luke went up to an apartment perched above a laundromat.

“ Fifteen sousands.” The senorita who beckoned him in was large and sat on a wide wicker chair. She leaned forward, her jostling forearms crossing over the silver head of a cane. She smiled at Luke. A web of saliva formed between her toothless gums when she opened her mouth. She reminded Luke of a turtle. A young boy stood next to her, his skin as brown as his eyes. He tilted his head, parted his lips slightly as if in amusement as he watched Luke.

“Fifteen thousand?” Luke tried to calculate that into U.S. dollars.

Senorita seemed to read his mind and laughed. “Fifteen sousands American dollars.”

“You’re kidding.”

She chuckled, her gums forming a cat’s cradle of spit. “No kidding.” She dabbed at the back of her neck with a white handkerchief. She nodded at her boy and mumbled something that Luke didn’t understand.

The boy reached for Luke’s elbow. “We go now.”

“Wait.”

The woman shook her head and waved at him as if shooing away a fly. “Go,” she said.

Outside, the boy nodded toward Amy. “What’s wrong with her?”

Luke stared at the boy. His tongue felt thick and dry. The sunlight felt sharp on his eyeballs. “Why don’t you ask her?”

The boy turned to Amy. “What’s wrong with you?”

Amy took the scarf off her head. “I picked the wrong beautician.”

“Bootishun?”

Amy shook her head. “I’ve got cancer.”

“Oh.” The boy nodded. “Sorry to hear.” He reached out and ran his dark brown fingers through the fuzz of Amy’s hair. “You got very pretty eyes.”

Amy squinted at him. She smiled. “Thanks.”

The boy turned to Luke. He seemed to study him. He grabbed Luke’s wrist. “Come,” he said. “Gimme the keys to your truck.”

“What?”

“Come on. I show you another way.”

“Another way?”

“Another way to see him.”

Luke stared uncomprehendingly.

“Padre Sapo,” the boy said. “The toad.”

“ I can’t take this anymore. I want to go home.”

Luke looked down from the grate, looked at his daughter slouching on the cold rock ledge, so pale and thin. How fast her thirteen years had gone by. Luke remembered the moment, the exact moment Jenna had told him she was pregnant; the smell of the lemon ammonia tile cleaner he’d just used, the sound of snowmobiles outside their window, the rerun of Cheers playing on their twenty-four inch Sony — it was one when Coach was still on. These memories were so deeply imprinted on his mind, because good God, how hard they had tried to get pregnant. It took them five years. Five years! And two rounds of in-vitro. And haven’t those thirteen years flown by so damn fast?

Читать дальше