By the time the fruit was the size of walnuts they dripped blood.

They whispered to me.

As they grew, eyeballs appeared. Dismembered fingers and toes. Lips moved. Tongues clucked disapproval. I heard them at night, giggling, commiserating, splintering through the wall to my soul.

Middle of the night, late September, I slid a black windbreaker over my pajamas, and grabbed a hacksaw from a hook in the garage.

As I sawed at the base of the apple tree, I ignored the apples dangling above me, ignored their accusations, the feel of blood dripping on top of my head. I ignored the smell of rot, and the sound of a gun being fired through a pillow into an old friend’s head.

Guilt is a dangerous thing.

I sawed it into small parts. No one woke up that night, no lights came on. The only sounds were the screams of dying apples as they hit the ground in a series of sickening splats, like the sound of skin being broken, like the sound of blood squirting across the ground.

Or across the sheets of a rumpled bed.

Guilt.

I will say this only once.

Six years ago, I killed one of them. One of my friends. I shot Paul through the head with his own revolver. He begged me not to, but he gave me no choice. It had to be done.

The day before, he called me on the phone and talked about guilt; of how he could no longer live with it, how he’d recently found out that Mr. Hench had family down in Tennessee who still visited the grave they’d erected when he disappeared from the face of the earth. Paul told me how he called Hench’s brother and talked to him, and told him he knew Mr. Hench, of how he’d pestered him, and how he was sorry for all the trouble he’d caused.

“What else did you tell him?”

I heard Paul crying on the other end. “Nothing. But I don’t know how long I can hold it in. It’s killing me.”

“Think of what it would mean to Polly. How could she support herself with you in jail?”

“I was only a kid.”

“Doesn’t matter.” My grip on the phone tightened. Sweat trickled from my ear into the receiver.

“Whatever happens, happens,” he said. “I can’t live like this.”

I paid him a visit the next night. Luck was with me. His wife was playing Bridge across town. He was asleep in bed when I found him. I told him I was sorry, but we’d made a promise.

I intended to hold him to it.

I grabbed his wife’s pillow, held it firmly over his face, and pumped two bullets into it. I worked fast to remove him, remove any evidence.

Polly came home a full hour after I left.

Guilt.

I pull up the old shovel from the grave beneath the apple tree and look up at the moon through the tree’s branches. Something catches my eye, silhouetted against the moon, a black pulsing orb, breathing like some hungry creature. There’s an apple left, after all.

I set down my shovel at the edge of the grave, my cigar halfway done, and walk quietly back to the electric fence. I hoist myself up and over via the maple branch, find my car and open the trunk.

Two years ago, Jack called.

Told me of how he wanted to tell someone, how he was thinking of seeing a psychiatrist to get some of the past off his chest.

“Have you told anyone yet?” I asked.

“No.”

“I don’t think it would be a good idea.”

“Is that what you told Paul?” he asked, and hung up.

At least Jack was still single. I didn’t have to worry about a wife, kids. When I entered his house, I found him sitting in an easy chair, a bowl of apples on his lap. He’d taken a bite from each one, and it was hard for me not to look at them, as they beat red and bloody like tiny hearts.

“I hear them sometimes,” he said as I emerged from the shadows dressed in black. “I hear them whispering to me.”

I waved my gun at him. “You want to talk about this?”

He set the bowl down. Lifted his own gun from his lap. “I knew you’d come,” he said. “I know you killed Paul.”

I kept my eyes on his weapon. “Is this how it’s going to be?” I asked. “A shoot-off between two old friends?”

He smiled. A sad smile. Tears in his eyes dripped down his cheeks, and met beneath his chin. “No,” he said. He lifted the gun. Pressed the nozzle to his temple and pulled the trigger.

Within the echo of the shot, I heard the bowl of apples at his feet laughing.

Guilt .

At least Jack had a proper funeral. I left him there like that. The only thing I didn’t leave alone were the apples. I picked up the bowl, holding them away from my body as they continued their wretched laugh, and put them down his garbage disposal one by one.

“Davy, I don’t know what to do. I can’t live like this. It’s eating me alive.”

Spence. Two days ago.

I didn’t think he’d break. Of all of us, I was sure he’d be the one to keep it together.

I invited him out to my house. Sent the wife and kid away. I didn’t bother trying to talk him out of anything. He was my brother, and I loved him.

Best, I thought, just to get it over with.

I pull Spencer out of the trunk of my car wrapped up in dark blue flannel bed sheets and hoist him over my shoulder. It’s a struggle getting him over the fence, but I manage.

I drag him to the grave. Lay him on top of Paul. Cover him with dirt and sod. Spread the dead fallen apples over it all.

One last apple high in the tree.

I hoist myself up into the branches, grab it, and twist it off its stem. I drop down beside the grave. Snuff out the remainder of my cigar. Polish the apple on my sleeve.

I’m able to look at it this time. Able to see it for what it really is.

The apple tree man doesn’t seem so old any more. He’s gotten younger as I’ve gotten older.

I bite into the last apple of the season.

Guilt is a monster that never goes away. Maybe it will catch up to me. Perhaps the need to tell someone might infest my soul like it had with Paul, Jack, and Spencer. I’m prepared for that. There’s a bullet left for me in case the need ever arises, and I’m ready to use it.

The bare branches of the apple tree are stark against the bright silver moon.

The apple tastes good. I take another bite.

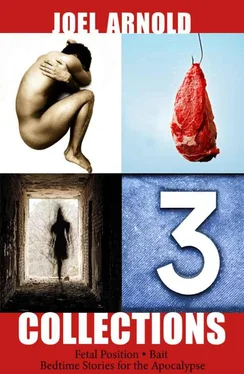

BEDTIME STORIES FOR THE APOCALYPSE

Bedtime Stories for the Apocalypsewas originally published in print by the wonderful Sam’s Dot Publishing. Please visit them at www.samsdotpublishing.comand support the small press.

Even over the acrid odor of an old school bus’s burning tires, a woman dressed in rags smelled coffee. Her mouth watered. Coffee . How long had it been? She stepped from behind the twisted metal that had been the bus.

“Care for a cup?” A young man sat by a small fire of burning detritus, a dented tin pail resting on the glowing coals.

“Is it real?” The woman stepped carefully over a path of broken glass and sharp stones. A smile fluttered across her lips.

The man held a cup out to her. Steam danced off the top. Her hand trembled as she took the cup and drank. She closed her eyes and breathed deeply through her nose, savoring the bitter taste.

“Good, eh?”

The woman dressed in rags nodded.

“You’ve got family left?”

She didn’t answer, taking another quick sip.

“It’s okay. I’d love the company,” the man said.

The woman handed back the cup. She looked back over her shoulder and whistled; two sharp blasts, followed by a long, high trill.

Two men emerged from behind the twisted bus, followed by another woman. They held makeshift weapons; a charred two-by-four, a piece of twisted rebar, a sharp-edged rock.

Читать дальше