“Lesley,” she said, “would you do me the honour?”

“Given it a lot of thought, have you?”

“A lot .”

“Do I have to buy a lime green dress with shoulder ruffles and a big fucking pink bow on my ass?”

“Yes.”

“Does Jeanie have to wear one?”

“No.”

Quiet on the line, then: “She’s invited, right?”

Sometimes, it was like no time at all had passed. Ann reassured her friend that all was well with Jeanie, and fielded a few questions about how she was doing, and explained that yes, Lesley was maid of honour because Ann liked Lesley better and had secretly taken her side in every dispute—and agreed with her that Jeanie would not look as good in lime green and pink as Lesley, and would be madly jealous when she saw her, teetering on those stripper heels through the Chicken Dance.

Ann did not ask Lesley if she had asked about Jeanie because she was still hung up on her… if it would have really been better if one or the other of them hadn’t been invited. In return, Lesley did not ask Ann about the quickness of the marriage, and if she mightn’t have jumped into it less from the dictates of desperate soul-searing love, and more as a consequence of her general isolation from the world; if her minuscule guest list might not indicate a more dangerous isolation, for a young woman set to marry a wealthy lawyer she’d only known for a few months.

Questions like those were best left to Eva Fenshaw.

Eva booked into a bed and breakfast in the little village of Vanderville on the Bench almost a week before the wedding.

What the hell? Ann wondered.

But Eva said she could afford it, and she loved the fall colours, and she wanted to be well-rested for the celebrations. And she didn’t want to be any trouble for the Rickhardts at their fancy winemakers’ house, which was where Ann and Michael were staying.

“I know I’m welcome,” said Eva before Ann could say it herself. “But I’m more comfortable here.”

When she drove out to see her, Ann admitted she could see how. The bed and breakfast was a two-storey, red brick, pink-gabled Victorian, just off Vanderville’s miniscule downtown. A chestnut tree shaded a big garden, still lush in the early autumn with nasturtiums overflowing clay pots and poking between field stone and little concrete gargoyles, still-flowering stalks of zabrina mallow growing everywhere. Its owner was a woman who might have been Eva’s baby sister: a menopausal earth-mom in peasant skirt and T-shirt decorated with the Mayan alphabet.

The ground floor was filled with crafty knickknacks that somewhat-less-than-casually suggested Christmas. Yes, Eva said when they settled down for lunch at Stacey’s, a diner on the town’s main strip—not five minutes from the B & B—her bedroom followed the festive theme.

“It’s like sleeping in a Christmas window display,” she said. “Quite some fun, actually, if you’re open to it.”

“If you say so.”

“I say so.” Eva smiled, and Ann smiled back. Although they spoke very regularly, they didn’t see each other in person much anymore, and that fact hit home with Ann as they sat there. Eva had aged visibly since they’d last had a meal together, a year or so ago; gained some weight, bent a bit here and there… her light brown bob was more grey. When Ann looked at her, she remembered her from a decade ago, taller, more tanned, not more than a wisp of grey in hair that went to her shoulders, telling Ann and her Nan about Tibet. The intervening years hung from her like debris.

“Thank you for coming,” Ann said. “It means a lot to us.”

“Oh, don’t say that.” Eva shook her head. “‘It means a lot.’ What’s ‘a lot’? A lot of what? A lot of hooey.”

“It’s something people say,” said Ann, knowing even as she spoke the direction the discussion would take, and so was utterly unsurprised when Eva said, “People hide behind words like that. They don’t say what they mean and then it’s all lies. Not that I’m calling you a liar.”

“Of course not.”

“And yet…” Eva lifted up the menu and read from it: “Chinese and Canadian Food. Do you suppose they have poutine?” She scanned down with a fingertip. “Oh they do!”

“That takes care of the Canadian part,” said Ann.

“I think I’ll have poutine. Imagine, living here all my life—and I’ve never had it before.”

“You’re on your own,” said Ann.

Eva clucked her tongue. “I wonder if they have herbal tea here? All it says is tea.”

“Should I ask?”

“I can ask.” Eva shut her menu, and signalled the waitress she was ready.

“Now tell me about this ceremony we’re having on Saturday,” said Eva after confirming that there was indeed herbal tea available, and that yes, the poutine was “any good.” “You’ve got your wedding dress. I bet you look lovely in it.”

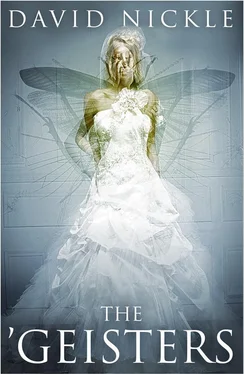

“I do,” said Ann. She took her phone out of her purse and showed Eva pictures on the tiny screen.

“Wow,” said Eva as she flicked through the images. “You’re a beautiful girl. Your Nan would be so—”

Ann put her hand on Eva’s and gave it a squeeze and Eva squeezed back. Eva and her Nan had come to be good friends before she died. Almost as good friends as Eva’d become with Ann in that time.

“So proud,” said Eva. “You’re getting married.”

“So I am.”

“Are you sure?” Eva looked at Ann levelly. She had been smiling the whole time, but now it faded. “It’s very soon.”

“Sometimes you know,” said Ann.

“That’s true,” said Eva. And as the steaming plate of fries, cheese curds and gravy arrived: “Michael is a nice fellow.”

“I’m glad you like him.”

Eva stabbed a french fry with her fork. She sniffed it. “You think I don’t like him,” she said, watching with fascination as a string of melted cheese curd snapped off the bottom of the fry.

“I—” began Ann, but Eva kept going.

“You think I’m coming here to bust this up, don’t you?”

Ann opened her mouth and closed it again. Yes, she had to admit, deep down she did think that. Eva didn’t like to travel. She didn’t like to sleep away from home. Ann had idly wondered if Eva wasn’t coming to town early to set up her B & B room as a kind of base camp for a more intensive campaign.

Eva squinted, popped the fry in her mouth and nodded as she chewed it.

“You know, we used to talk. A lot more. You’d tell me everything. And I’d tell you everything too. And when I said I thought somebody was a nice fellow, it was because I meant it. And I mean it now. Michael Voors is a nice man.”

“For a lawyer?” asked Ann.

Eva shrugged. “Can’t say I’ve known very many,” she said, and her smile broke out again, and they both laughed.

“You’re taking a step in your life,” continued Eva. “You’re taking it more quickly than we would have, when I was your age…. My God—Creator—that’s an awful thing to hear yourself say…. But it’s a good step all the same. I’d be more worried if we were sitting here five years from now, and you hadn’t taken any kind of step—that’s an awful thing to say too, because there’s nothing wrong with being independent either.” She put her fork through a clot of gravy and starch and twisted it like it was spaghetti. “But you know what I mean.”

“I don’t really have any idea,” said Ann.

“Only this,” said Eva. “You’ve got my blessing. Michael… He is a nice man. I can tell, you know. And you… If you’ve got any doubts or second thoughts… Well, like you said, sometimes you know. I don’t think you really have doubts, now do you?”

She raised her eyebrow, and Ann said, “I don’t. No.”

Читать дальше