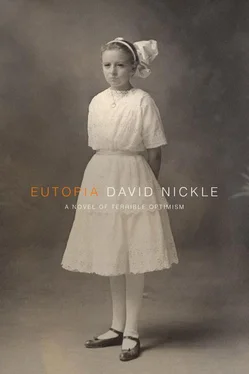

David Nickle

EUTOPIA

A NOVEL OF TERRIBLE OPTIMISM

To Tobin, in hope and love

Dr. Charles Davenport

c/o The Eugenics Records Office

Cold Spring Harbor, NY

August 15, 1910

Dear Charles,

The infant is safe.

I want to set that down before anything else. I shall write it again, and swear to it, and underscore it, so there can be no doubt:

The infant is safe.

I trust this will set your mind at ease. After the communiqué that you will have doubtless received from Garrison Harper by now, I can only imagine you must be gravely concerned. We have had words here in my library, Harper and I.

I believe that I have answered his accusations, primarily concerning my methodology in dealing with the Trout Lake investigation. But I am under no illusion that he went off satisfied. No doubt he is sitting at his desk in that vulgar mansion of his on the hill, composing his libel as I write this. He will send his letter off with a rider this evening. I must wait until morning. Thus will you receive Harper’s account before mine.

I might predict what it will tell you: that the doctor, in a fit of depravity, abandoned his scientific observation of the mountain people, against the express orders of Harper, and invaded their community—plied them with drink, beat a young mother with a walking stick, snatched her baby from its cradle, and ran, like a madman, into the deep mountain night.

The doctor (Harper will have written), in so doing, violated the very principles of Compassion, Community and Hygiene, upon which the fair Eliada rests.

Harper will beg you to agree to the doctor’s dismissal. He will insist that you send a physician who will content himself seeing to those principles—a physician who does not preoccupy himself with matters of science—who understands the practicalities of administering society take precedence over all. He will question the doctor’s—my—fitness. He will tell you that I have harmed an infant.

These are lies, Charles. I did not feed liquor to mountain men. I did not strike a woman with my stick.

The infant is safe.

If all goes well, shortly I will provide you with the testimony of the men who had accompanied me: Mr. Bury and Mr. Wilkens. They will attest as true, that when we found the infant, it was abandoned—left in a bed of dried needles and sap at the base of a pine tree.

Really, can one be surprised? The people of these hills are degenerate. They are the flotsam of the wagon trains of the last century, left here to fester in their immorality, for generations.

Bury found it. He was scouting the edge of our camp at dusk. Bury came running back as Wilkens and I were heating tins of stew on the kerosene cook stove and admiring the view of the Kootenai River Valley in the vanishing light.

He was in a state of near hysteria, which was unusual—for Mr. Bury is as hard a man as Eliada sustains. At first, he was unable to explain what it was he found. It was a fire that produced no heat; a great bird, that cried out in song, with a voice like a woman’s; a beast; and some other things also, which he could not clearly describe.

I did feed Bury a small jigger of whiskey then, but only to calm his nerves such that he could lead us back to the spot, where I might observe this thing he’d found firsthand.

It was some distance from the camp—further than Bury ought to have ventured in a simple patrol. He intimated that he may have been following the song, which caused him to stray, and he became quite apologetic.

The pine tree where the infant rested was part of a small copse of them, growing from a flat ledge near a stream. Facing the east, it was in growing shadow. The infant lay on its back there, staring up into the pines. It cried out, pitiably, as we approached. Bury pointed, his hand shaking, and I confess that I scolded him.

“It’s a baby,” I said. I crouched beneath the branches and finally approached the infant on hands and knees, met its eye for the first time. “Nothing more.”

And so I ordered Wilkens to give me his coat. Folding it into a makeshift blanket around the infant, I lifted it to my chest and made my way back to my men. Then we returned to the camp, and I took the infant inside the tent.

This, Charles, is what transpired. The infant was abandoned. I saw to it that it came to no harm.

When we returned to Eliada, I brought the infant straight to the hospital. It sits here at my side now, in a cradle brought up from the nursery. I do not even entrust its care to the nurses here. I will not so much as permit them to see this child—and I shall not let it out of my sight—because here is the truth of the matter:

This infant that we found in the woods—on the side of mountain… it is magnificent. Where the indigenous folk here are bent and degenerate, subject to the gigantism and the harelip and criminality which is a consequence of their breeding… this child is, how shall I say? It is perfection. It is the height of nature. It is a Mystery, or—dare I say it—a Miracle.

Rest assured—no matter what Harper suspects, now or later… this child will come to no harm. I will not allow it. The infant is safe and I shall ensure that safety with my life—with all the life I have.

Were I so equipped, Charles, I swear that I would suckle this child myself.

Yours in Service, Nils Dr. Nils Bergstrom Chief Physician-in-Residence Eliada Hospital Eliada, Idaho

APRIL, 1911

Not ghosts.

Although their owners might have pretended otherwise, Dr. Andrew Waggoner knew it. The sheets that loitered and whistled and kicked at the mud on this dark hillside in northern Idaho tonight were not ghosts; nor were they devils, nor duppies, nor spectral things of any kind.

When Andrew was a good deal younger, his Uncle Elmer had told him: ghosts were what the Ku Klux Klan originally intended with those sheets they wore. They wanted to make the poor Negroes think they were beset by the implacable spirits of the dead, Devils straight up from Hell—and not merely small-souled white men with lynching on their minds.

Maybe on some other Negro, the evil light of the kerosene flame in the twilight would make a mix with all those flapping sheets, that eerie un-musical whistling noise they were making, and that would be enough. But Andrew Waggoner was not that kind of Negro and he knew.

These were not ghosts.

They’d got Andrew just outside the hospital—done the deed as the last of the sun fell toward the pine-toothed edge of the Selkirk Mountains, west of Eliada. If he’d been paying better heed, not been smoking and brooding and keeping to himself, Andrew might have seen who they were. He didn’t think anyone would be caught wearing their mama’s bedsheets that close to town.

It didn’t really matter much, of course. The truth of his predicament was awful in its simplicity: five men in sheets. One Negro, tied and on his knees. How does something like that end well?

Andrew did not think of himself as a religious man, but as one of those sheets bent down in front of him, he thought about praying.

As matters resolved, however, he didn’t have to pray or even make up his mind on the matter. If God was paying any attention at all, He spared Andrew the indignity of supplication by tossing down a bone.

“You are going to watch this, Dr. Nigger.”

The man in the sheet spoke in a voice Andrew thought he might recognize.

“It is Waggoner,” said Andrew. “Dr. Waggoner.”

He said “doctor” slowly, because he wanted to make that part of his name especially clear right now. Andrew Waggoner was a doctor, trained by some of the finest surgeons at Paris Medical School, graduated with honours, Class of 1908; he had been a resident here at Eliada’s hospital for nearly a year. He was not some hog-tied vagabond nigger that these men could feel right about killing.

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Fesselspiele mit Meister David [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/486693/david-jagusson-fesselspiele-mit-meister-david-har-thumb.webp)