Kim Robinson - The Wild Shore

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kim Robinson - The Wild Shore» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Orb, Жанр: Социально-психологическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

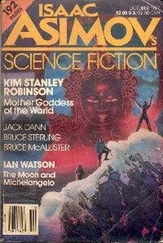

- Название:The Wild Shore

- Автор:

- Издательство:Orb

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:978-0-312-89036-0

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Wild Shore: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Wild Shore»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Wild Shore — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Wild Shore», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It wasn’t just the clothes that distinguished the scavengers. They all talked loudly, all the time. Perhaps they did it to overcome the silence of the ruins. Tom often said that living in the ruins made the scavengers mad, every single one of them; and quite a few of them passing me had a look in their eye that made me think he was right—a look wild and wanton, as if they were searching for something exciting to do that they couldn’t quite find. I watched the younger ones closely, wondering if they were among those who had run us out of San Clemente. We had had small fights with a group of them before, at the swap meets and in San Mateo Valley, where rocks had flown like bombs—but I didn’t see any of the members of that crowd. A pair of them walked by dressed in pure white suits, with white hats to match. I had to grin. My blue jeans had had their knees patched countless times. All the folks from new towns and villages wore the same sort of thing, back country clothes kept together by needle and prayer, sometimes new things made up of scraps of cloth, or hides; wearing them was like having a badge saying you were healthy and normal. I suppose the scavengers’ clothes were another sort of badge, saying that they were rich, and dangerous.

Then I saw Melissa Shanks walking out of our camp, carrying a basket of crabs. I hopped up without a thought and approached her. “Melissa!” I said, and gave her a fool’s grin. “Want some help bringing back what you get for those pinchers?”

She raised her eyebrows. “What if I was out to get a pack of needles?”

“Well, um, I guess you wouldn’t need much help.”

“True. But lucky for you I’m out in search of a barrel half, so I’d be happy to have you along.”

“Oh good.” Melissa spent some time working at the ovens; she was a friend of Kathryn’s younger sister Kristen. Other than the times I’d seen her at the ovens, I didn’t know her. Her father, Addison Shanks, lived on Basilone Hill, and they didn’t have much to do with the rest of the valley. “You’ll be lucky to get a half cask for that many crabs,” I went on, looking in her basket.

“I know. The Blue Book says it’s possible, but I’ll have to do some fast talking.” She tossed back her long black hair confidently, and it blazed in the sun, so glossy and perfectly kept that it seemed she wore jewelry. She was pretty: small teeth, a narrow nose, fine white skin… She had a whole series of careful, serious, haughty expressions that her lips would hold, and that made her rare smiles all the sweeter. I stared at her too long, and bumped into an old woman going the other way.

“Carajo!”

“Sorry, mam, but I was made distract by this here young maiden—”

“Well get a grip!”

“Indeed I’ll try mam, goodbye,” and with a wink and a pinch on the butt (she slapped my hand) I rounded the crone, who was grinning. As Melissa was smiling too I took her arm in hand and we talked cheerily as we toured the meet on the main promenade, looking for a cooper. We eventually made for the Trabuco Canyon camp, agreeing that the farmers there were good woodworkers.

A plume of smoke rose from the Trabuco camp, floating through wedged sunbeams that turned the smoke seashell pink.

We smelled meat; they were roasting a steer half by half. A good crowd had gathered in their camp to join the feast. Melissa and I traded one of the crabs for a pair of ribs, and ate them standing, observing the antics of a slick trio of scavengers, who wanted six ribs for a box of safety pins. I was about to make a joke about them when I remembered Melissa’s father. Addison did a lot of trading by night, to the north, and no one was sure how much he traded with scavengers, how much he stole from them, how much he worked for them… He was sort of a scavenger himself, who preferred to live outside of the ruins. I chewed the beef in silence, aware all of a sudden that I didn’t know the girl at my side very well. She gnawed her rib clean as a dog’s bone, looking at the sizzling meat over the fire. She sighed. “That was good, but I don’t see any barrels. I guess we should look in the scavenger camps.”

I agreed, although that would mean a tougher trade. We walked over to the north half of the park, where the scavengers stayed—keeping a clear route back home, perhaps. The camps and goods for trade were much different here: no food, except for several women guarding trays of spices and canned delicacies. We passed a man dressed in a shiny blue suit, trading tools that were spread out over a blanket on the grass. Some of the tools were rusty, others brighter than silver, each a different shape and size. We tried to guess what this or that tool had been for. One that gave us the giggles was two pairs of greenish metal clamps at each end of a wire in a tube of orange plastic. “That was to hold together husbands and wives who didn’t get along,” Melissa said.

“Nah, they’d need something stronger than those. They’re probably a doorstop.”

She crowed. “A what? ” But she wouldn’t let me explain—she started to double over every time I tried, until I couldn’t talk myself. We walked on, past large displays of bright clothing and shiny shoes, and big rusty machines that were no use without electricity, and gun men with their crowd of spectators, on hand to watch the occasional big trade or demonstration shot. The seed exchange, on the border between the scavengers’ camps and ours, was hopping as usual. I wanted to go over and see if Kathryn was trading, because the way she traded for seeds was an art; but in the crowd of traders I couldn’t see if she was there, and suddenly Melissa tugged on my arm. “There!” she said. Beyond the seed exchange was a woman in a scarlet dress, selling chairs, tables, and barrels.

“There you are,” I said. I caught sight of Tom Barnard across the promenade. “I’m going to see what Tom’s up to while you start your dealing.”

“Good. I’ll try the poor and innocent routine until you get there.”

“Good luck.” She didn’t look all that innocent, and that was the truth. I walked over to Tom, who was deep in discussion with another tool trader. When I stopped at his side he clapped a hand on my shoulder and went on talking.

“—industrial wastes, rotting wood, animal bodies, sometimes—”

“Bullshit,” said the tool trader. (“That too,” the old man got in.) “They made it from sugar cane and sugar beets; it says so right on the boxes. And sugar stays good forever, and it tastes just as good as your honey.”

“There are no such things as sugar cane and sugar beets,” Tom said scornfully. “You ever seen one of either? There are no such plants. Sugar companies made them up. Meanwhile they made their sugar out of sludge, and you’ll pay for it with no end of dreadful diseases and deformities. But honey! Honey’ll keep away colds and all ailments of the lungs, it’ll get rid of gout and bad breath, it tastes ten times better than sugar, it’ll help you live as long as me, and it’s new and natural, not some sixty-year-old synthetic junk. Here, taste some of this, take a fingerful, I’ve been turning the whole meet on to it, no obligation in a fingerful.”

The tool man dipped two fingers in the jar the old man held before him, and licked the honey off them.

“Yeah, it tastes good—”

“You bet it does! Now one God damned little lighter, of which you’ve got thousands up in O.C., is surely not much for two, twooooo jars of this delicious honey. Especially…” Tom cracked his palm against the side of his head to loosen the hinges of his memory. “Especially when you get the jars, too.”

“The jars too, you say.”

“Yes, I know it’s generous of me, but you know how we Onofreans are, we’d give our pants away if people didn’t mind our bare asses hanging out, besides I’m senile almost—”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Wild Shore»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Wild Shore» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Wild Shore» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.