The little girl stared at Eugène-Olivier with enormous blue eyes. One tangled curl annoyed her by falling across her face. She impatiently pushed it away with her hand. On her little palm, which looked as if it had been carved from ivory, there was also blood.

“Valerie!” Jeanne called her in a soft voice. “Valerie, I have something for you, come here!”

The little girl paid no attention. She continued to gaze at Eugène-Olivier.

“So you sent the devil back to hell and you think the job is finished?” Valerie finally said. “But the Mother of God is still crying. Do you know where she lives? She has a big, beautiful house with multi-colored windows. But the buttocks are in her house now. She didn’t invite them, but they came anyway. The Mother of God doesn’t want the buttocks to go there anymore. Come on, do something—you’re grown ups!”

Father Lothair and Sophia observed the girl with sadness, but without surprise. Jeanne got down on her knees and pulled a big, round Chupa Chups lollipop from her pocket and tried to lure the girl, holding the candy toward her in her outstretched hand.

“I don’t want it!” Annoyed, the little girl pushed the candy away. Her left hand was also wounded, quite strangely, in exactly the same place as her right—in the middle of the palm. Her bare feet were also injured identically, just above the toes. Although they were not large, all four wounds were bleeding.

“Come on, please take it, Valerie,” Jeanne cajoled her. “I stole the lollipop just for you. The buttocks could have caught me! But you don’t want it and my feelings are hurt.”

The little girl made a face and reluctantly took the candy but she did not unwrap it; she pressed it in her hand and approached Sophia Sevazmios.

“Sophia, dear Sophia, do something so they can’t go there anymore! You can do it, I know you can!”

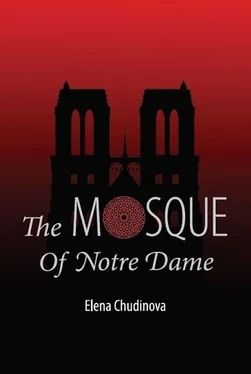

“No, Valerie, I can’t. For you I would, but really I cannot.” Sophia Sevazmios spoke with the child as if she were speaking to an equal, although her voice softened a little. “Please understand that my soldiers and I cannot expel the buttocks from Her house as you would like us to do. My army is so small we couldn’t hold Notre Dame for a week.”

“You can, you just don’t want to know how! And I can’t help you! The Mother of God won’t let me help you!” And Valerie burst into tears, smearing dirty rivulets on her face.

“What is this all about? How did she hurt herself like that?” Eugène-Olivier asked Jeanne quietly. They moved away from the priest and Sophia. “Why doesn’t someone bandage her wounds?”

“She didn’t hurt herself,” Jeanne looked at Eugène-Olivier peculiarly.

“Look, you don’t stab yourself like that by accident! How did she get those wounds? Who would dare do such a thing to her?”

“I guess you don’t know about stigmata.”

“No.” The word seemed vaguely familiar, like the letters IHS.

“The wounds of Christ… They appear of their own accord, and they bleed. It happens to some saints, to the righteous. Valerie is a fool for Christ. She knows everything about everyone; it’s impossible to deceive her.”

“Why does she call the Muslims ‘buttocks’?”

“Have you ever seen them at prayer—at salah?”

“Of course.”

“What’s the only part of them you see?”

Eugène-Olivier whistled.

“She’s little. She says what she sees. If only you knew how afraid they are of her! She goes all over Paris and threatens them with her fists and she stamps her foot at them… But most of all, she loves Notre Dame.”

“Notre Dame?” Eugène-Olivier couldn’t help noticing that Notre Dame had been on his mind all day, painfully reminding him of its existence.

“Yes, she calls it the house of the Mother of God. And she wants us to expel them from it. She often goes around crying because it’s now a mosque—”

Just then, Valerie came runing up to Eugène-Olivier. “Your grandfather was good,” she said very seriously. “He’s in Heaven now. And you, will you chase them out?”

She moved closer to Eugène-Olivier, then turned around and headed toward the door. She sang softly in a remarkably pure, ethereal voice:

Meunier, tu dors,

ton moulin va trop vite!

Meunier, tu dors,

ton moulin va trop fort!

(“Miller, you’re sleeping!

Your mill turns too quickly!

Miller, you’re sleeping!

Your mill goes too fast!”)

Her little figure, a statuette dressed in rags, had almost reached the door. But first she turned, faced Eugène-Olivier once more and shook her finger sternly.

“I don’t know anything about your grandfather,” said Jeanne, “but now you probably understand why everyone is so afraid of her.”

Tears fell from Jeanne’s gray eyes and their black lashes as she watched Valerie depart. Jeanne did not seem to notice that she was crying.

“No one knows where she came from or what happened to her family. She’s always barefoot, even in winter, and she sleeps in the streets. Don’t even bother offering her shoes and warm clothes. Once in a while I manage to bathe her or at least comb her hair. But for that, I have to catch her in a particularly good mood. What she is, I can’t imagine. I think sometimes she eats nothing all week except the Holy Eucharist. She loves to nibble on the leftover hosts; Father Lothair always leaves them for her.”

“I told Father Lothair that I don’t believe in God and he intentionally changed the subject,” said Eugène-Olivier.

“I should warn you he’s quite sly.”

“And you… you do believe?”

“Of course,” she said with surprise. “I’m not a fool.”

“Thanks. Then why are you killing them? Aren’t you supposed to sit and pray or something?”

“I asked you not to ask me that!” said Jeanne intensely. “You’ve touched a sore spot. A very sore spot. During the Crusades, I would have lived well, but my soul is really not mature enough for Judgment Day. Or maybe I’m not brave enough. Don’t laugh, but it’s true: It takes more courage to sit, pray and wait for someone to come and kill you than to fight a war.”

“I understand.” Eugène-Olivier really did understand. Only an hour ago, he couldn’t have imagined anything of the sort.

Sophia had finally taken her box of cigarettes, pulled one out, flattened it with her fingers, and put it into her cigarette holder.

“Unhappy girl,” she said, blowing out smoke.

“The girl is extremely unhappy,” replied Father Lothair. “But I’m not talking about the younger girl. I mean the older one. Valerie is above our human understanding. She has consolations available to her that we cannot even imagine. But Jeanne Saintville is torn in two by her heart and her soul. Like evenly matched horses.”

“For you, those are two different things. For me, they are not.”

“Is that true, Sophia? Have you forgotten what they have threatened us with these days?”

“Of course not. I really want to tell you something, Father. Perhaps tonight. Would that be possible?”

“Closer to midnight, yes. Now I must go to the ghetto to someone who is dying. God knows how long I will stay there. But after that, I will wait for you.”

Jeanne was already running through the corridor leading to the church, confusing Eugène-Olivier, who was following her. In front of the next metal gate, she stopped and pressed some kind of metal plate.

“Here it is, the cell for guests. Normally, it’s used by visiting monks.”

The tiny room looked more like a ship’s cabin in the old films. Only there was no porthole. The ceiling was right above one’s head, and the bed was attached to the wall. Jeanne opened and closed the wardrobe doors a few times, showing empty shelves for clothing, some folded blankets and a few books. There was a small shower behind frosted glass in one corner. There was nothing else except a glass table with a single, asymmetrical leg. At this point, Eugène-Olivier was not surprised by the small, wooden cross on the wall with some juniper branches stuck behind it.

Читать дальше

![Виктор Гюго - Собор Парижской Богоматери [Notre-Dame de Paris]](/books/30985/viktor-gyugo-sobor-parizhskoj-bogomateri-notre-thumb.webp)