And I, Jon Hoff told himself, I am that man. One man. Could one man do it?

He thought about the other men. About Joe and Herb and George, and all the rest of them and there was none of them that he could trust, no one of them to whom he could go and tell what he had done.

He held the ship within his mind. He knew the theory and the operation, but it might take more than theory and more than operation. It might take familiarity and training. A man might have to live with a ship before he could run it. And there'd be no time for him to live with it.

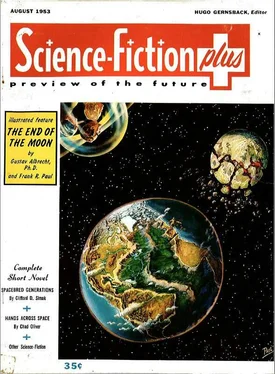

HE STOOD beside the machine that had given him the knowledge, with all the tape run through it now, with its purpose finally accomplished, as the Letter had accomplished its purpose, as Mankind and the Ship would accomplish theirs if his brain were clear and his hand were steady. [4] The idea of such an educational device was first advanced in 1911 by Hugo Gernsback, editor of this magazine, in his science-fiction classic, RALPH 124C 41+. In that story the machine was called a hypnobioscope. Experiments in the use of such a device dates back to 1922, when it was used at the Pensacola Training Station by the United States Navy to teach the Continental Code. The theory behind the experiments is that when a person sleeps his subconscious still is open to suggestion and can therefore learn. In fact, actual experience has proved that many individuals who fail to master a subject while awake are able to master it while asleep, and there is ground for the belief that knowledge impressed upon the brain of a sleeper will be retained longer and in clearer detail than a lesson learned while awake. Mr. Gernsback, in RALPH 124C 41+, pointed out that one advantage to such an educational device would be the useful employment of sleeping time, which is now waste time so far as any actual human improvement or advancement is concerned. He envisioned a society which would read all its books, do all its studying while asleep, which would mean that the eight hours usually wasted in sleep would be spent as reading time, thus resulting in a vastly better educated society. Experiments have been carried out recently by the British Overseas Airways, the Institute of Logopedies at Wichita, Kan., the institute of language and linguistics at Georgetown University, and by Charles R. Elliott, psychologist at the University of North Carolina. In all these experiments pillow-mike or earphone arrangements have been used, repeating over and over again the lesson which the sleeper is to learn. This, however, would seem to be a crude approach to the problem, and there is no doubt that, before the concept can be employed to full advantage and employed in mass education, some drastically different method must he found. It is my understanding that such a method is now in process of development.— The Author.

And if he knew enough.

There was yet the chest standing in the corner. He would open that—and it finally was done. All that those others could do for him would then be done and the rest would depend on him.

Moving slowly, he knelt before the chest and opened the lid.

There were rolls of paper, many rolls of it, and beneath the paper books, dozens of books, and in one corner a glassite capsule enclosing a piece of mechanism that he knew could be nothing but a gun, although he'd never seen one.

He reached for the glassite capsule and lifted it and beneath the capsule was an envelope with one word printed on it:

KEYS.

He took the envelope and tore it open and there were two keys. The tag on one of them said: CONTROL ROOM.

The tag on the other: ENGINE ROOM.

He put the keys in his pocket and grasped the glassite capsule. With a quick twitch, he wrenched it in two. There was a little puffing sound as the vacuum within the tube puffed out, and the gun lay in his hands.

It was not heavy, but heavy enough to give it authority. It had a look of strength about it and a look of grim cruelty, and he grasped it by the butt and lifted it and pointed and he felt the ancient surge of vicious power surge through him—the power of Man, the killer—and he was ashamed.

He laid the gun back in the chest and drew out one of the rolls of paper. It crackled, protesting, as he gently unrolled it. It was a drawing of some sort, and he bent above it to make out what it was, worrying out the printed words that went with the lines.

He couldn't make head or tail of it, so he let loose of it and it rolled into a cylinder again as if it were alive.

He took out another one and unrolled it and this time it was a plan for a section of the ship.

Another one and another one, and they were sections of the ship, too—the corridors and escalators, the observation blisters, the cubicles.

And finally he unrolled one that showed the ship itself, a cross-section of it, with all the cubicles in place and the hydroponic gardens. And up in the nose the control room and in the back the engine rooms.

He spread it out and studied it and it wasn't right, until he figured out that if you cut off the control room and the engine room it would be. And that, he told himself, was the way it should be, for someone long ago had locked both control and engine rooms to keep them safe from harm. To keep them safe from harm against this very day.

To the Folk the engine room and control room had simply not existed, and that was why, he told himself, the blueprint had seemed wrong.

He let the blueprint roll up unaided and took out another one, and this time it was the engine room. He studied it, crinkling his brow, trying to make what was there, and while there were certain installations he could guess at, there were many that he couldn't.

He made out the converter and wondered how the converter could be in a locked engine room when they'd used it all these years. But finally he saw that the converter had two openings, one beyond the hydroponics gardens and the other from within the engine room itself.

He let go of the blueprint and it rolled up, just like all the others. He crouched there, rocking on his toes a little, staring at the blueprints.

Thinking: If there were any further proof needed to convince me, there lies that simple proof.

Plans and blueprints for the ship. Plans dreamed by men and drawn by human hands. A dream of stars drawn on a piece of paper.

No divine intervention. No myth.

Just simple human planning.

He thought of the Holy Pictures and he wondered what they were. They, too—could they, too, be as wide of the mark as the story of the Myth? And if they were it seemed a shame. For they were such a comfort. And the Belief as well. It had been a comfort, too.

He crouched in the smallness of the vault, with the machine and bed and chest, with the rolled-up blueprints at his feet, and brought up his arms across his chest and hugged himself in what was almost abject pity.

He wished that he had never started. He wished there had been no Letter. He wished that he were back again, in the ignorance and security. Back again, playing chess with Joe.

Joe said, from the doorway: "So this is where you've been hiding out."

He saw Joe's feet, planted on the floor, and he let his eyes move up, following Joe's body until he reached his face.

The smile was frozen there. A half-smiled smile frozen solid on Joe's face. "Books!" said Joe.

It was an obscene word. The way Joe said it, it was an obscene word.

As if one had been caught in some unmentionable act, surprised with a dirty thought dangling naked in one's mind.

"Joe—" said Jon.

"You wouldn't tell me," said Joe. "You said you didn't want my help. I don't wonder that you didn't ..."

"Joe, listen . . ."

"Sneaking off with books," said Joe.

"Look, Joe. Everything's all wrong. People like us made this ship. It is going somewhere. I know the meaning of the End . . ."

Читать дальше