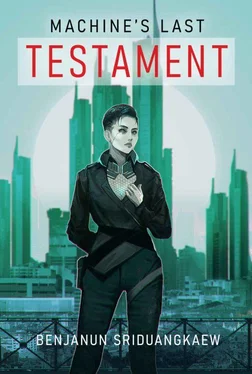

Benjanun Sriduangkaew

MACHINE’S LAST TESTAMENT

Evening, verging on nightfall. In the sterile cleanness of Suzhen’s office there is the smell of war, familiar and earthy: soot and sweat, dried gore, sickness. Candidates are sent as is—a phrase that’s always struck her as faintly mercantile, not for people at all—to give them no time to prepare, and therefore no time to dissemble. She gazes across her desk at a man from one of the asteroid colonies, bent and parched, looking a decade older than he is. Frail from starvation, scarred from combat or abuse: no telling which. In the halfway houses and centers that accommodate refugees there is little order, and the wardens who run them aren’t known for gentleness. There are beatings, sometimes more. It is against regulation but it is nevertheless an open secret; everyone knows what goes on. There is nearly no point curbing or protesting it. Beyond her purview in any case.

She continues to study the man, his blanched skin, the dark circles under his eyes. The nose that broke and did not heal well, the colorless clothes given to all arrivals that hang on him loose and shapeless. Once she thought, entering this field, that she would be crippled by sympathy. That to all who enter she would say yes, yes, yes, you too deserve Samsara’s grace, we have so much, welcome to Anatta. But the process dehumanizes. Each person becomes a dossier, a collection of risk factors and potential to contribute, to be weighed against one another and then weighed against Bureau guidelines. And always at the back of her mind there is the quota. An agent can accept just so many in a month; any excess she would have to personally sponsor, become responsible for. Excess, even that is a measure which reduces personhood to quantity.

To be a citizen is to deserve.

Suzhen’s quota for the month is nearly over.

Even after two years in this post, she still doesn’t know how to deliver judgment. She’s tried the slow approach, gently, but that merely leads to her candidate trying to bargain—as though no is a commodity that can be haggled over, bribed into a yes . They’d tell her of their families and their tragedies, false or real, though there’s never a shortage of real ones. None ever admits to what camp wardens do to them and it is easy, she thinks, to take that as a sign nothing untoward happens in the camps. The bruises, the wounds, those could simply be a product of brawls between inmates. Inmates. She has tried to find other words but this one sticks, the official terminology. It used to be that she called them her clients, but that was absurd. She does not serve their interests. She is their enemy.

“I’m sorry,” Suzhen says, after one more nominal look at the man’s profile. Even for a colony, his home was unusually poverty-stricken before it was depopulated and annexed by a warlord. He is not particularly educated, has little to offer Anatta, has a history of misdemeanors while in detainment. Noncompliance, attempted theft of food, physically unfit for factory labor either on-planet or on Vaisravana. “I’ll have to put you on a waitlist. You can try again next month.”

Sometimes they react in fury and attack her, and they’d be taken away—truly away, cast out of Anatta. Sometimes their eyes would glitter with the hope she’s raised with the words next month . A few take it stoically. This man bursts into tears, there’s no transition between his silence and the howling that erupts; he is on the floor, hand over mouth as though he too is trying to stop the sound, but it comes through loud, uncontrollable and inconsolable. A single continuous scream, it is astonishing what the human throat is capable of, all that raw noise. It vibrates through her bones, impossibly seismic, until her temples ache. He is taken away by the pair of drones that guard her room. She doesn’t like human security. Drones use no more force than necessary.

What is it about desperation that takes away all dignity, what is it about that lack of dignity that lowers a person in her regard. What is wrong with her, she could ask of herself. Suzhen turns off the channel that links her datasphere to her work terminal. In her ear her guidance says, “Citizen, your stress indicators are elevated. You’ve been granted two hours off and may leave early.”

Very nearly she laughs. She supposes it will soon ask if she wishes to schedule a counseling session. Most selection agents have to. They receive counseling and behavioral calibration more frequently than most civil servants. For the average administrative personnel their subjects are abstract, collated into numbers, statistics. For Suzhen they are immediate, physical, hopelessly here .

Suzhen strides past the doors to her coworkers’ offices, then past the lobby where candidates wait their turns. The same smell here. Not entirely filthy, they’re screened for contagion and allowed a minimum of hygienic care, but it is not the filth that thickens in her throat like smoke. Rather it is desperation, the reek of broken things. She meets no one’s gaze. The slightest eye contact is signal: they will crowd around her, pleading, offering, grasping at her before the guards restrain them. Hungry ghosts.

On the balcony she looks down at the expanse of city, this part one of the neatest, despite the contents of the lobby she’s just left behind. Her guidance murmurs to her, suggesting destress routines, opening a submersion channel that promises deep, dreamless sleep tonight. Instead she takes out her cigarette case. Half a dozen cylinders, each prettily faceted, jewel-toned. Emerald, ruby, sapphire. She lights a green one, waits for the substances within it to cook, and takes a long inhalation. The smoke rises, inlaid with phantasmagoria, snakes and rushing jade currents. Cosmetic—it interacts with her visual implants—rather than hallucinogenic, since her guidance no longer allows her to indulge in anything stronger. Even what is in the cigarette is harmless, just sufficient to ease her nerves, lowering adrenaline and cortisol. Her jaw relaxes. She didn’t realize how hard she was grinding her teeth. By habit she hates wasting anything, a bad habit inherited from her mother and leaner times, so she extinguishes the cigarette and puts it back in its case, the butt blackened and smeared from her mouth. She tracks the trajectory of a taxi across the air, its lean segmented body gleaming in the autumn light. It is a perfect evening, crisp and filigreed, the building in which she stands and the building across a marvel of Mobius arches, honeycombed windows, curlicue balconies and inverted hanging gardens. On Anatta everything, every moment, is full of grace.

“I’m taking a walk,” she says. “Find me someplace with minimal foot traffic.”

“You ought to be home by nine, citizen,” the guidance chides, but it obliges with a list of the nearest places where she can stretch her legs. It doesn’t always. For every action it weighs the variables of her well-being, even an act as innocent as taking a walk. There was a time when it forbade her from going near any sort of bridge, high roof, or exposed balcony. There was a time when all sharp things were removed from her vicinity. Samsara’s wisdom protects every citizen, especially from themselves.

Huajing Station is quiet this time of the day, alabaster floor thinly peopled, pristine vending machines in hibernation. Refugees from the halfway houses are flown in on secure vehicles, so that citizens never have to catch sight of them on public transport. Her gaze passes over the sparse crowd and her filters notify her—citizen class prime, citizen class theta, probationary resident, citizen class prime… She looks away; it isn’t a setting she can toggle off, even outside the office. Agents from the Selection Bureau don’t enforce, but they are duty-bound to report anything amiss, the ones who do not belong, a noncitizen where they shouldn’t be. The nearest Interior Defense officer would then take over.

Читать дальше