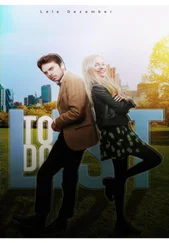

Leo looked at me intently, and I knew he expected me to speak. It was he who had come to my work, though, and I hadn’t prepared anything. The text was a huge step for me, and I hadn’t yet figured out what would follow it. I convinced myself I’d probably never hear from Leo again.

Yet here he was.

He kicked back in his chair and slung one arm over the back, his eyes never leaving my face. Feigning confidence, I continued to meet his eyes, which had the uncomfortable effect of making me want to touch him again. Even though I stopped talking to Leo, even though I totally fled when he probably needed me most, and even though I made it a point to move on with my semblance of a life, I couldn’t dispute the fact that I. Liked. Leo.

Shit.

It was so much easier being with guys I didn’t like. Davis went off to join the army, and I hadn’t thought about him since. For all I knew, he was dead, too, right alongside Leo’s brother.

Leo’s brother. Right then it hit me what it could have been like if I were with someone like Leo when my dad died. I doubt he would have left me out of fear like Davis left me.

Like I left him.

“I am such an asshole,” I said, not quite meaning to, aloud.

Leo didn’t disagree.

“I was your Davis,” I decided. “I should just go off and join the army.”

“Who’s Davis? And there’s no way you’re joining the army.”

“Don’t tell me what to do,” I argued.

“You seriously want to join the army? All five feet of you?”

“I’m five foot two, and, well, no. I don’t want to join the army. I just need to stop speaking.”

“You already did that, remember?” Leo looked smug.

“What are you doing here, Leo? I have no idea what to say to you. I’m not going to apologize anymore because I did that and apologies are really just bullshit to make the apologizer feel better. And I don’t deserve to feel better. I should feel like absolute, total shit. I deserve someone to take out my tendons and parade me around like a marionette.”

“Diarrhea mouth, can you plug it for a second?”

The thought of having plugged diarrhea in my mouth shut me up.

“I’m not looking for another apology—” Leo started, but I cut him off.

“I don’t know what to give you. I have nothing to say that will make anything better. Nothing is going to bring Jason back, and it’s totally my fault.” Wait. What?

“Alex, how could Jason’s death be your fault?” Leo unhooked his arm from the chair and put his hand on the table near mine, but not touching.

“I don’t think I meant that. I mean, of course I didn’t.” I picked at a jagged fingernail.

“Do you think your dad’s death was your fault?”

“No,” I argued. “But I just don’t get it. Any of it. I don’t want any more real horror in my life. There’s nothing funny about actual death and disease. If only my dad could come back because of a rabid monkey at the zoo.” I laughed to myself at the ridiculous horror movie sentiment.

“Or as a reanimated prostitute,” Leo added.

“Maybe we should have buried them in pet cemeteries,” I suggested.

“That never ends well,” Leo admitted. I had never joked about my dad’s death with someone, not someone who had a death of their own to joke about.

“Do you believe things happen for a reason?” Leo brought the conversation back to serious.

“No,” I answered emphatically.

“Me neither,” he concurred. “I can’t buy the idea that we’re supposed to live and learn from horrible things. That somehow these things happen so we can grow as people.”

“I hope nothing else happens to you,” I told him, “because you have done enough growing.” I held my hand over my head acknowledging his exceptional height.

“Maybe that’s why shit does keep happening to you. Because you need to grow. Shorty.”

“That was quite possibly the lamest insult anyone has ever bestowed upon me.”

“Forgive me. I’m out of practice. Being away from everyone except your depressed parents will do that to you.”

“That sucks,” I said. “You should come back to school. Better of two evils? I’m there.” I prodded.

“So that would make school the bigger of two evils.” Leo smiled, and one of his fingers stroked one of mine. My toes wiggled.

“Alex! A little help here!” I hadn’t noticed that the snowy eaters had arrived, and a line was backing up.

“I guess I have to go work.” I rolled my eyes.

“That is what they pay you for.” Leo stood as I did.

“I thought it was for my bubbly personality and smaller-than-average butt.”

“Imagine the tips if you had an even average-sized butt.”

“You’re lucky I still feel guilty, or I might have to hit you.” I started walking behind the counter.

Leo grabbed my arm. “No more guilt, okay?”

I nodded weakly. Guilt was the one thing I’d held on to for everyone. “So you’re saying I shouldn’t blame myself for you smoking again?” I raised an eyebrow.

“Let’s say you were a coconspirator, but I was the mastermind.”

“I can live with that.”

“Good.”

“Alex!” Doug yelled again. “I need more meat!”

“Should I be jealous?” Leo asked.

“I wouldn’t mind if you were.” I almost felt coquettish, if such a thing were possible. We both smiled.

“Alex! Meat! Now!” Doug harassed me.

“Better go give Doug his meat. See you in school?” I suggested. “There’s a book closet that misses you terribly.”

Leo pulled a chain out from his shirt that hung around his neck and held it up for me to see. I recognized a familiar-looking key and the distinctive shape of dog tags. He tucked the chain back in, gave a small wave and a smile, and walked up the stairs.

I felt really good. And it scared me.

NO LEO THE REST of the week at school, nor the entire next week. We started texting, benign conversations about movies on Svengoolie. I subtly tried to coax him back to school, but I was afraid to push it.

They’re threatening to start construction on the book closet wing if you don’t show up.

Nice try. That’s not scheduled until next year.

I might knock it down myself then.

That I’d come to see.

But the days passed, and that was as much contact as we had. I started to believe I imagined our Cellar visit, residual brain fog from Becca’s pot smoke. She was having a particularly nauseous time from the radiation combined with the sore throat. I did my best to cheer her up with visits and pints of ice cream, but it didn’t feel like enough. It never did.

Becca’s mom was in a particularly dark, religious state. Every moment she could get away from the house, she did. Sometimes it was shopping, sometimes spa days, but she spent most of her time at the synagogue. On the rare occasion I did see her, I wished I hadn’t. One afternoon, when Becca seemed to ache in the most random places, her mom walked in with a grossly pained expression. I think Becca’s cancer installed at least six new worry wrinkles on her mom’s face. She tutted, clicked her tongue, made all sorts of exaggeratedly worrisome sounds as she watched Becca on her bed. Under her breath, I heard her say, “God will see you through.” Then she left again. Unsettling.

“What is up with your mom?” I asked, taking over game duty from Becca. She liked to think of herself as my sensei to the world of RPGs, and I complied as long as she agreed to watch Waxwork I and II with me. I bought the set with some birthday money from Aunt Judy.

“She’s like the prophet of doom.” Becca’s voice was quiet and scratchy, but her head was together. I liked that. “She thinks it’s a bad sign that I’m so sick, even though I’m done with chemo.”

Читать дальше