“No’am,” Aviva said, coming towards him among the trees. No’am stared at her. “A… Aviva,” he stammered, “What are you doing here?”

“What did you do with that letter?” she asked.

“Oh, it’s nothin’, just a game.”

“A game? What kind of game?”

“Nothin’.”

“No’am, you told me you never go anywhere near these woods. Aren’t you afraid they’ll ambush you here? Aviel and his pals?”

“No, not really.”

“I’m surprised. What are you hiding?”

“Nothin’, I told you. Don’t be such a bore.”

“So what’s the game?”

“I don’t want to tell you.”

“Okay. Can I guess who you sent the letter to?”

His eyes narrowed. He looked at her suspiciously. “I have to go,” he said. He took a few steps, and suddenly disappeared.

“No’am,” she called.

He returned. “We have a problem,” he said. “If I leave you here you won’t find your way back.”

“What’s going on, No’am? Does it have anything to do with Tehila?”

“Tehila? Why should it? Tell you the truth, I don’t know.”

“You sent this letter to Solon Aquila, didn’t you?”

No’am started. “How did you guess?”

“Why would you send a letter to a character out of a story?”

“’Cause sometimes they come.”

“They?”

“Those I send letters to through this mailbox.”

“That boy that Aviel claimed you brought in for help?”

“His name’s Bobby. He can…. Well, in the story his stepmom is abusing him and he can make silhouettes with his hands, live ones, and then he calls a creature out of the shadows to come take her. I wrote to him to come out and help me. After I’d read the story I went for a walk in the woods, and suddenly I got here, to this mailbox, and I thought, why don’t I send this Bobby a letter to come help me. And that’s what I did, and he did come. But… but he was more wicked than in the story. He brought creatures out of the shadows, scary creatures, and they attacked Aviel and his pals.”

Aviva looked at him, shocked. He’s pulling a fast one on me , she thought. His inventions are getting more sophisticated. Like Father’s .

“Then I wrote to those kids from this story, ‘Ararat,’ the ones who came from another planet and were afraid to show their powers, and their teacher, too. They looked nice. Only they weren’t so nice. They made fun of me and spat at me.”

“The… flying kids? They were for real? And their teacher? The one who makes hail?”

No’am nodded. His face seemed sad. “They didn’t go away as fast as Bobby. They shouted that next time I call ’em, they’d have enough power to get me as well.”

“I knew it, I knew it all has to do with those magazines Tehila gave you. What is she up to, Tehila?” said Aviva.

“At least some of the magazines,” said No’am. “I don’t know why, but it doesn’t always work.”

“You tried some more?”

“Yeah. I sent a couple of letters to people from other stories, but nothing happened. And somehow I knew nothing would happen. Those stories, they weren’t….” he fell silent.

“They weren’t what, No’am?”

He looked at her in horror. He was terrified. “They weren’t alive, like the ones that you picked.”

“That I picked?”

Now Aviva felt as alarmed as he was. Her hand went to the locket. The woods started closing in on her. She tightened her fist around the silver egg. No’am kept looking at her, waiting for an explanation.

“Do you know what Solon Aquila does?” she asked.

“Yes,” said No’am. “I asked him to come over here and make Aviel’s worst nightmares come true.”

“You didn’t get the point, No’am,” she said. “Solon empties people of their childhood, after letting them live their fantasies. He takes away their inner world, all their dreams. He leaves them with nothing.”

“Here he comes,” said No’am. His voice was trembling.

In the air, beside a eucalypt standing not far from them, a block of air lit up like a flame. The woods shook. Aviva squeezed her left hand around the locket. She whispered, “The locket, Daddy’s locket….” With her right hand she held on to No’am.

She shuddered, thinking of flying kids.

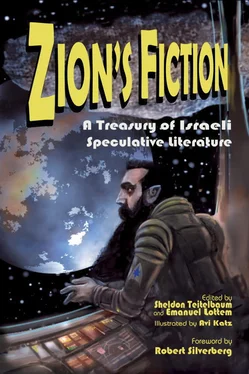

Afterword

Aharon Hauptman

It was in 1996, during the first annual convention of our newly founded Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy. I proudly strolled, with Emanuel Lottem and other friends, through the corridors of the Tel Aviv Cinematheque, crowded with enthusiastic young fans. One of them stared at me, and I could hear him whispering in a friend’s ear: “I think this is Aharon Hauptman, he was the editor of Fantasia 2000 .” And his astonished friend replied: “What? Is he still alive?!”

Well, here I am, twenty years later, alive and kicking (or at least trying to), and what is more important, the Israeli SF scene is alive, kicking more than ever. Yes, there are no regular printed magazines anymore (the time of printed magazines is over anyway). But the online activity is flourishing: three or four sites, rich in contents. Conventions attract thousands of visitors each year (amazingly, sometimes two parallel events competing with each other), an annual collection of original stories is regularly published, several local publishers specialize in SF, Hebrew SF is being translated, Israeli writers win awards, films are produced, academic theses are being written. Who would have dreamed about this back in 1978, when we conceived the late Fantasia 2000 , the first Israeli SF magazine that besides translations encouraged submission of original Hebrew stories? (Funny, once upon a time the year 2000 sounded futuristic).

Well, we dreamt. Science fiction is the stuff of dreams, isn’t it? SF dreams (and nightmares) are products of imagination, but they are inspired by reality, and they shape reality by inspiring and enriching human knowledge and actions. I write these words just after attending an academic meeting about artificial intelligence. The chairman reminded the audience that the origins of AI and robotics are rooted deep in SF. They will soon be an integral part of our lives. The same with space travel, of course, as well as with human-machine interface, cyberspace, cyborgs, nanotechnology, you name it. And, as every SF fan knows (or should know), the point is not the technology (real or fictional), not even speculative science, but their interaction with humans, with us. Good SF can help us to better understand how we are (or will be) shaped by science and technology and how science and technology are (or will be) shaped by us. For me, an SF story at its best is a thought experiment about alternative realities, with plausible technoscience ingredients, in a way that makes you think differently and perhaps better understand our world, other worlds.

If humans fail to understand our potential futures, our alternative realities, it is mostly due to the failure of imagination, something that the SF community is not short of. Arthur C. Clarke wrote (in Profiles of the Future ) that although only a very small fraction of SF readers would count as “reliable prophets,” “almost a hundred percent of reliable prophets will be SF readers—or writers.” Today, we should better replace the word “prophets” with “futurists” or “foresight practitioners,” as foresight and futures studies are finally (but yet not sufficiently) taking their place in research and policy making.

What’s more, in these fields (which don’t deal with prophecy but with analyzing alternative futures) there is growing interest in the contribution of SF and SF thinking. We constantly face unforeseen surprises in economy, politics, climate, and technology that challenge conventional thinking and methods. In order to enrich the outcomes of foresight studies and to strengthen their effectiveness, it is important to encourage nonconsensual views about potential wild cards: future events with (currently perceived) low likelihood but high impact. And there is no better source of wild ideas for wild cards (including their possible implications) than science fiction. Yes, you may think about teleportation.

Читать дальше