Aviva moved her eyes, looking around the room. All those guys’ names. “All this stuff….”

“Yes,” said Tehila. “Keepsakes.”

“There were many of them.”

“Sure. Usually, the story lasts for just a few months.”

“And then what? They leave?”

“No. I get tired.”

“And you tell them to go away?”

“No. I kill them and capture their essences inside some object that belonged to them.”

Alarmed, Aviva immediately turned her roving eyes to look at her. Tehila laughed. She went to a glass cabinet. Behind its doors there were small books bound in leather, neatly arranged. “Sometimes I need more than an object to remember them by.” She took one of them out. Now Aviva saw that each of those books bore one of the names attached to the objects. The one Tehila handed to her was marked “Shim’on.” Aviva opened it—a photo album, not a book. Shim’on and Tehila on the beach, Shim’on and Tehila with a tower in the background, Shim’on and Tehila somewhere at night. In all those photos Tehila looked just the same, the way she looked ever since Aviva had seen her first, in those bluish cracked lacquer shoes. But Shim’on was changing. Growing older. She followed the sequence of photos, and her heart stopped. Froze. In this photo, yes, in this photo, under the big tree—a walnut tree, she knew—Shim’on and Tehila, and behind them, on a bench in the corner, someone. Not someone. Her father. She said, “that’s Daddy,” in a broken voice, and raised her eyes to Tehila, and Tehila bent to see for herself, and said, “That’s right, I never realized Netan’el was here. How strange. He really was friends with Shim’on.”

Aviva grasped her locket, closed her hand around it, squeezed. She felt the room closing in on her; she had to get out. She picked up one of the Fantasia 2000s and started for the door, actually ran, and her forehead hit the frame head, but she didn’t feel it. She went out of the house. Her mother was sitting on the couch staring at the TV set, which was turned off, and she ran out to the porch, and there she stopped. From a distance she saw No’am approaching. He was limping. He mustn’t see me cry . She tightened her lips. “Who did you fight with this time?” she asked, making every effort to smile.

“None of yer business.”

“Sit here a moment, I’ll get you something to drink.”

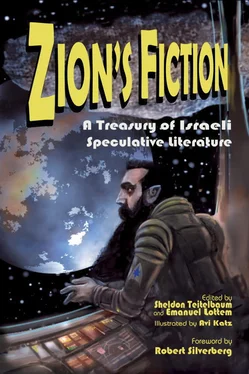

She went inside, came back with a glass of Coke and saw that No’am was sitting, bristling with anger, and that he was crying. He, too, was crying. “Look, No’am,” she said. “Look.” She pointed at the magazine. He wouldn’t comply. She felt his frustration radiating out of him, shining like a little sun. She extended her hand to caress his hair, which was exactly like their father’s, dark and smooth. He pushed her hand away, rudely, and she grasped her locket the way she always did when she didn’t know what to do with her hands. With her left hand. With her right hand she opened the magazine, issue number 41, she saw, and leafed through it fast. “Look, No’am, aliens and spaceships, like in the books Daddy used to like.” No’am looked at her. His eyes were bright, bright because of his tears. She cringed and squeezed her locket tighter. With her other hand she pointed at a random page. “Shadow, Shadow on the Wall,” it was titled. “An interesting one, seems to me,” she said desperately, looking closely at No’am, but his eyes were glued to the page. He was swallowing the words. “No’am,” said Aviva, but No’am didn’t reply. He picked up the magazine and, walking and reading, went into the house.

Aviva wasn’t quite sure what it was all about. She sat all morning in the backyard, in the shade of the trees, reading Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey . About some stupid girl who begins to suspect that the mansion in which she’s a guest conceals dark secrets. Obviously, there aren’t any; she only fell in love with the son of the host family, and she’s making up all this just for kicks. Nevertheless, Aviva never noticed how fast time was passing. It was already noontime and hot, and sun rays were filtering through the treetops—sacred fig and Indian banyan and sycamore—in bright, shiny patches, but what brought her out of her book was the sound from the front of the house; there was a woman on the porch, and she was shouting. She bolted for the front of the house. Tehila, too, emerged from her den. But not her mother, who remained on the couch. On the porch stood a heavyset woman, her black hair splayed over her shoulders. She was holding a tall, skinny boy by the hand. Would have been handsome if he weren’t so full of sharp bones, she thought. Bigger than No’am, who was leaning against the wall by the door, on the other side of the table. No’am looked very calm. He even grinned. He crossed his arms and looked back at her.

“I’m gonna break both that boy’s legs,” said the woman. “You just let me lay me hands on ’im and you’ll see.”

“What happened?” Aviva asked. She was looking at Tehila, who didn’t answer her.

“Yer brother, that little bastard, see what he done to m’boy.”

Aviva saw. The boy’s arms, his throat, and every other bit of exposed skin were covered with blue bruises. She turned to look at No’am. “You did this?”

“Not just to ’im,” the woman added, “a couple more kids, m’boy’s friends. I’m gonna tear ’im to pieces. And you,” she said to Tehila, “you got nuttin’ to say? You got no control over the kids yuh brung into the neighbor’ood?”

Tehila said, “Take a good look at No’am, see how small he is. Half the size of your son. You really believe he can beat up your son and his friends?”

“You tell ’er,” said the woman to her son. “C’mon, ya little jerk, tell ’er.”

“He got help,” said the boy, sucking in the snot threatening to drip out of his nose. “He brung another kid to the woods.” He pointed in the general direction of the woods at the edge of the neighborhood, a place Aviva had passed once. “That’s where we was playin’.”

“Two boys?” said Aviva. “Against a hulk like yourself?”

“I wanna go,” said the boy, pulling at his mother’s hand. Tak, tak, tak , Tehila’s shoes sounded as she went down to the gate and opened it for them. The woman gave her an angry look but stepped down from the porch. Then she turned around and said to No’am, “I’m warnin’ you. You come near m’boy, it’s the end of you.”

The grin Aviva thought she had seen on No’am’s lips grew wider. He waved them both good-bye.

“What was that all about?” asked Aviva.

“No clue,” said No’am. And Tehila looked at him again, her frown returning to spoil her carefully painted face.

No’am came to her room at night, asking whether he could get more Fantasia 2000 magazines. He liked these stories, he said, and Aviva sent him to Tehila, and he returned with the whole bunch of them. “Help me pick a story,” he said. “The one you chose earlier was a good one.”

“I’m too tired,” Aviva said. “Choose for yourself.”

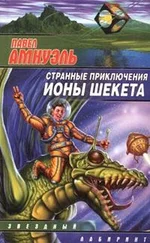

He went through the magazines and finally selected one by its cover illustration.

The next evening he came back. All roughed up and disheveled, like scuzzy hair in the morning, she thought; the neighborhood kids must have caught up with him. “What happened?” she asked. “You got beaten?”

“Help me pick a story,” he said. “I can’t find any I like.”

“Come on,” said Aviva. “Don’t be such a lazy dog. Next thing you’ll ask me to read to you.” They were sitting in the living room. Their mother was sitting there too, chewing on a piece of bread Aviva pushed into her hand. The food on her plate was getting cold. “Can’t you see I’m busy?” And to their mother, “Come on, Mommy, you’ve got to eat.” And their mother said, “I’ve already told you. Me, I have nothing to eat for.”

Читать дальше