A strange one she was, Tehila. All dressed up, perfect makeup, looking ready to go to a party, her hair pulled back in a ponytail, and her makeup—rouge and blue eyeliner. Also what she wore, a simple dress, but nearly an evening gown. Yet, and this was the funny bit, her shoes didn’t fit. That is, they were perfect colorwise, but they were old, cracked, blue lacquer shoes. What’s with all this blue? Aviva asked herself, her hand moving to grasp the locket she wore on a chain around her throat, becoming a fist over that oblate silver egg. She wasn’t quite sure what it was actually, except that her father had given it to her before he was gone.

She almost screamed, now it was just almost a scream. All through that month her pain folded in on itself, becoming a hard shell, so she didn’t cry now when she remembered; it was only the pain banging on the shell from the inside, and she felt the thuds of these bangs, and she almost screamed. There were no stabbing pangs now, like there were when she’d heard from the soldiers who came to speak with her mother, to say things that her mother had already guessed, in the middle of the night, and she woke up and got them out of bed, screaming horribly, and No’am clung to her not understanding anything; fear made him cry, but she’d already realized, though she wasn’t ready to admit it, until the soldiers came. And a couple of weeks later the war in Lebanon was over, but it made no difference to her; she felt the Katyushas that kept falling and the fire that kept burning, breaking pieces off her brain. Then she screamed too, because knives were cutting her inside, every one of her organs was being cut, and seeing her mother give up and start decaying, and No’am uncontrollable and full of rage and looking for pretexts to quarrel, she tried to choke down on her screaming, breathe it in, soften those knife thrusts, and she almost made it, she just almost screamed, and soon she’ll lose her pain completely and will remain empty of her father, his memory, all those moments when he was her father and she was somebody’s daughter, and she’ll get on with her life. She knows this, it wasn’t she who’d set the price, only her locket will remain, sort of an oblate sphere, and she couldn’t figure out why somebody should have made it in the first place, and her father’s words, “Aviva, so that you don’t forget.”

She started crying. Not really crying. She just allowed a few tears to get out. Tehila sensed, how fast she sensed those tears, and came beside her and held her tight. “Well,” she said, “no way you’re staying here. You’re coming to live with me.”

Live with her? In another city? Their mother hardly complained. She said, “The one I lived here for is gone,” and Tehila just took her by the hand after Aviva had packed up for the three of them, but No’am ran out and kept running and running until he got to the royal poinciana tree—she knew its name because her father made her memorize the names of trees and flowers and birds—and No’am started climbing, holding on to its branches. And Tehila went out there, her lacquered shoes going tak, tak, tak on the pavement stones, and Aviva, standing at the window and watching, could hear her shoes even at this distance, but what Tehila whispered to No’am, which made him climb down off the tree and come with her, she couldn’t hear. Even though she saw her lips move.

There was still a week left of the summer vacation, before they had to go to school. Both of them would go to the local high school, which included a junior high, since No’am was just going on to seventh grade and she to tenth, and No’am wasted no time getting on the wrong side of the neighborhood’s kids. Kids in Yehud were tougher, and Tehila’s home was at the end of town, in a neighborhood of old single-family houses, and it is well known that kids in single-family-house neighborhoods are the toughest. It’s been a few days already that No’am would come home bruised and bleeding. Always, their mother lets her glance linger on him, and Tehila looks bemused, with this frown that doesn’t fit in with her made-up face. And Aviva takes him by the hand and cleans his wounds with iodine or Polydine, or puts on a compress, and gives him a piece of her mind, but he doesn’t listen, he just tightens up his lips and growls behind them.

“This can’t go on,” Aviva said to Tehila. Since their arrival they haven’t talked much. Tehila showed them their rooms. She had a big house, with a den—she called it her study—in which she enclosed herself all day, working on her sculptures. She was unmarried and had no children, and when Aviva asked, she just smiled and said nothing. But her old lacquered shoes she wore every day, even when working in her study. Aviva saw some of the sculptures. They repelled her, deformed human figures that they were, with too many hands or too few, with two heads and sometimes more than one mouth where mouths aren’t supposed to be, nor tongues, and still more parts sticking out or gaping, which Aviva recognized but was too embarrassed to tell herself what they were. And all of them, all these monsters, wore new shoes. Sometimes Nike or New Balance or Timberland, sometimes shiny with high heels, or square-toed leather shoes. Tehila also had a library. A huge one. In her living room. It had all of Jane Austen’s novels. And Aviva, who had read only Pride and Prejudice , felt hope biting at her chest.

“No,” said Tehila, “this can’t go on.”

“He needs something to keep him busy,” said Aviva.

“I wish he would read, like you.”

“But once, before, he used to read.”

“Like what?”

“Books you don’t have in your library. Adventures, and thrillers, and fantasy.”

“But I do have fantasy,” said Tehila, giving her a long stare. “And science fiction.”

“My daddy…”

“I know. You think it would help No’am?”

“I never saw any of it in your library.”

“It’s not in the library.” Tehila turned her back and made a few steps toward her den. “Come on,” she turned back to Aviva, “follow me.”

The far wall of her den had a small door Aviva hadn’t noticed before. A low one. Tehila walked in with a straight back. Aviva, taller than Tehila by a head, had to bend to pass through.

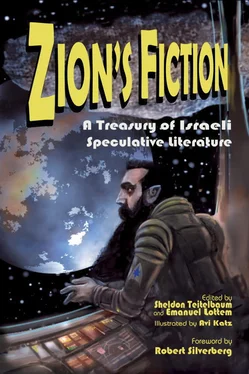

A strange room. Even stranger than the den. On tall stands and in glass cabinets of all sizes there were assorted disassociated objects, including a jug and a watch and a book and a razor blade and a wallet and a handheld computer and a pair of eyeglasses and more. Each display cabinet was labeled by name: Alon. Dan. Yogev. Levi. Yaron. Yekutiel. Zvulun. And more. Aviva thought, only guys’ names. And the room looked like a museum . Tehila went to a large glass cabinet holding a cardboard box. Aviva saw the label: Shim’on. Tehila lifted the box effortlessly, although Aviva suspected it must be quite heavy, and put it on a table in the middle of the room. “There you are,” she said. Aviva opened the box and looked inside. A pile of glossy magazines, brand new. On the top one she saw Fantasia 2000 printed in yellow letters, and the cover was purple and blue with an illustration of an alien traversing the sky in a teacup. Interesting , she thought, and started digging in. All those magazines inside had the same title, Fantasia 2000 . Must be magazines from way back, she told herself. The year 2000 was a long time ago.

“There are stories here No’am will find interesting.” Tehila answered the question she meant to ask.

“They’re yours?”

“No,” said Tehila. “They’re Shim’on’s.”

“Who’s he?”

“One of my ex-lovers,” said Tehila, looking at her closely. Aviva turned pink. “He used to collect all these magazines. This one was important to him, helped him consolidate his identity as a reader. At least, that’s what he claimed.”

Читать дальше