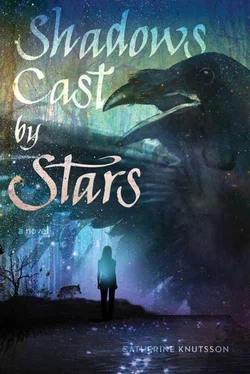

Catherine Knutsson

Shadows Cast by Stars

© 2012

Writing a book is a collaborative task. I am so grateful for the many eyes and hands who have touched this story as it made its way from idea to book.

To Caitlyn Dlouhy and her team at Atheneum: my gratitude for helping me polish this story until it shone.

To the River Writers: Shari, Kristin, Diana, and Sheena, for all the laughs and support and advice along the way.

To my international cast of writer friends: Deb, Jo, Rabia, Ryan, Cat, and Jen, for reading the various drafts and offering such sage and generous advice. And especially, my undying thanks to Elena, for pushing me and encouraging me to break the rules I had created for myself. I am a better writer and better person for knowing you.

To the women of SIFM: such shining examples of strength! My gratitude for your unwavering encouragement, support, and friendship.

To my sister, Carmen, for always being there, no matter what.

To Diana Fox: my heartfelt thanks for all that you have done. You have been a true champion and friend through all this. I couldn’t have done it without you.

And, last but never least, to Mikel Knutsson, for picking me up when I fell down (repeatedly!) and for never losing faith in me, even when I had lost it myself.

W e live the Old Way. Our house, constructed of wood timber and roofed with asphalt shingles, straddles the boundary where the wasteland and the northernmost edge of the Western Population Corridor meet. This land was once my great-grandfather’s farm. Once was. Hasn’t been for a long time.

Every morning, my brother and I rise before dawn, make the trek to the mag-station, and ride into the Corridor to attend school, where we plug into the etherstream via the chip in our forearm. By law, our chip-traces can’t display any information about race, religion, or sexual orientation, but our classmates have always known that Paul and I are Others, of aboriginal descent, marked by the precious Plague antibodies in our blood.

Every afternoon, we make the return trip, riding the mag-train to the end of its line before walking back home along the old dirt road. Behind us, smog from the Corridor reaches north, stretching its ugly yellow fingers as far as it can as it tries to snatch up the last of the habitable land. Not long ago, a reserve was here, lodged in the Corridor’s throat, but all that remains now is our home. We are the only ones who have stayed, clinging to what little is ours, defiantly living as we always have, without computers and etherstreams and data-nets in our home, without food gels, without central heat. This is our choice. This is what it means to live the Old Way.

Today the walk seems longer than usual, because Paul isn’t talking to me. He got into a fight earlier in the day, but it’s not his split lip or his gashed knuckles that have me so worried. Paul’s on disciplinary action for fighting and truancy as it is, which is tough on both of us. Why can’t you be more like your sister? the teachers always say to him. Why can’t you help your brother? they say to me. We’re twins, Paul and me, but we’re not alike-not anymore, at least. Paul’s always had a short fuse, but lately it’s gotten shorter.

Now he walks beside me, slump-shouldered as his battered raven flies next to him. The raven is Paul’s shade, his spirit animal, and it always shows up after something bad happens to him. Today it was some kid who was looking for a scapegoat to blame for his brother dying of Plague. The rest who joined in? Well, no one in the Corridor needs an excuse to stick it to an Other.

Paul notices me watching him. “What’s wrong?” he asks as his shade casts him in the wavering light where spirit and flesh merge. The raven looks as beaten and bruised as Paul.

“Your raven. He’s back.”

Paul glances over his shoulder, but there’s nothing there for him to see. Only I can see the shades, even though I don’t seem to have one of my own. Paul’s gifts run a different path. “Well,” he says with a sigh, “at least it’s here and not at school.”

He’s right. When shades come to me, they sometimes take me under into the twilight world of spirit. More than once, I’ve been trapped there, unable to find my way back to my body. I fear that one day I’ll drown in the heavy darkness of the other side. But not today. Today I watch Paul’s raven and worry, for there’s one thing I know: When a shade comes to visit, something is about to change.

We round the last corner of the road, and the moment our house comes into view, Paul’s raven takes flight, leaving my brother lighter, unfettered. Paul may not like it here, but this place is good for him. Under the watchful eyes of the old windows, my brother is whole. He races inside to change out of his school clothes, the old floorboards creaking under his movements. It’s not long before he pounds back downstairs and flies through the kitchen, grabbing the last biscuit from breakfast before disappearing outside.

I always leave the last one for him.

I wait until I hear the sound of Paul’s ax striking wood before I go inside and close the door, leaning against it to seal the Corridor, school, the Band, the entire world outside. We have made it through another day. Our family is still together, if not whole.

For one complete minute, I allow myself to pretend we’re safe. The minute ends, as it always does, and reality sets in. Time for chores, but first I need to hide the contraband in my schoolbag: twine, twigs, old pencils, paper clips, elastic bands, tossed-away shirts, a red ribbon, a bundle of rusted keys. The family magpie, my father calls me. He doesn’t like that I take castaway items hiding in the school basement or in the lost-and-found, forgotten, homeless. No one may want them, but it’s still stealing, he says.

I do it anyhow. One day I might need an elastic, or a scrap of leather, or a length of wire. That’s what I tell myself, but most of these things, ancient and obsolete, will end up in a weaving, or a basket, or a dream catcher for Paul. This is how I pass my time when the night falls and we’re left in the dark, because I don’t need to see to work with my hands. I need only to feel.

The twine and paper clips and the other cast-off junk spill onto the table the moment I unbuckle my school bag. Sunlight glints off the keys, and for a moment they seem to wriggle like bright blue herring, a fresh catch, ready to be devoured.

I blink and they are keys again.

The Old Way is a way of work. We have no electricity, no running water, no garbage collection. Our luxuries are born of our own hands. The Old Way keeps us honest, my father says. It keeps us connected to the earth.

That doesn’t stop me from thinking about a day, a week, a lifetime in the Corridor. Even with the rolling blackouts, they have heat in the dead of our brutal winter. Their bones don’t ache when the rains come, nor do they have to haul in wood when squalls descend from the north, blanketing the world with snow-not to mention it’s a lot easier to hide from the searchers among the millions in the Corridor. Here, we’re exposed, and there’s not much stopping them from coming to gobble us up.

In the Corridor I would find a job, and with the money I earned, I would buy my father a new armchair so he had somewhere comfortable to sit after a hard day of work. I would buy myself a new wool coat and a pair of boots to keep my feet warm in the winter.

Читать дальше