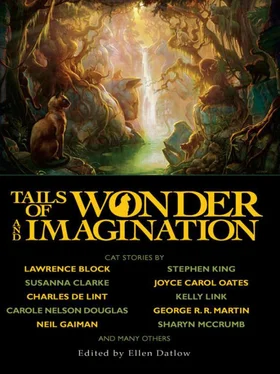

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Mother, don’t be absurd. He’s been dead for ten years.”

I lowered myself into a chair. I was shaking by then, and I fancied I saw a half-smile on the glass cat’s cold jowls.

“Get me out of here,” I said. A great weight crushed my lungs. I could barely breathe.

With a look, I must say, of genuine worry, Eleanor escorted me onto the porch and brought me a tumbler of ice water. “Better?” she asked.

I breathed deeply. “A little. Eleanor, don’t you realize that monstrosity killed your sister, and mine as well?”

“That simply isn’t true.”

“But it is, it is! I’m telling you now, get rid of it if you care for the lives of your children.”

Eleanor went pale, whether from rage or fear I could not tell. “It isn’t yours. You’re legally incompetent, and I’ll thank you to stay out of my affairs as much as possible till you have a place of your own. I’ll move you to an apartment as soon as I can find one.”

“An apartment? But I can’t…”

“Yes you can. You’re as well as you’re ever going to be, Mother. You only liked that hospital because it was easy. Well it costs a lot of money to keep you there, and we can’t afford it anymore. You’re just going to have to straighten up and start behaving like a human being again.”

By then I was very close to tears, and very confused as well. Only one thing was clear to me, and that was the true nature of the glass cat. I said, in as steady a voice as I could muster, “Listen to me. That cat was made out of madness. It’s evil. If you have a single ounce of brains, you’ll put it up for auction this very afternoon.”

“So I can get enough money to send you back to the hospital, I suppose? Well I won’t do it. That sculpture is priceless. The longer we keep it, the more it’s worth.”

She had Stephen’s financial mind. I would never sway her, and I knew it. I wept in despair, hiding my face in my hands. I was thinking of Elizabeth. The sweet, soft skin of her little arms, the flame in her cheeks, the power of that small kiss. Human beings are such frail works of art, their lives so precarious, and here I was again, my wayward heart gone out to one of them. But the road back to the safety of isolation lay in ruins. The only way out was through.

Jason came home at dinner time and we ate a nice meal, seated around the sleek rosewood table in the dining room. He was kind, actually far kinder than Eleanor. He asked the children about their day and listened carefully while they replied. As did I, enraptured by their pink perfection, distraught at the memory of how imperfect a child’s flesh can become. He did not interrupt. He did not demand. When Eleanor refused to give me coffee—she said she was afraid it would get me “hyped up”—he admonished her and poured me a cup himself. We talked about my father, whom he knew by reputation, and about art and the cities of Europe. All the while, I felt in my bones the baleful gaze of the Cat in Glass , burning like the coldest ice through walls and furniture as if they did not exist.

Eleanor made up a cot for me in the guest room. She didn’t want me to sleep in the bed, and she wouldn’t tell me why. But I overheard Jason arguing with her about it. “What’s wrong with the bed?” he said.

“She’s mentally ill,” said Eleanor. She was whispering, but loudly. “Heaven only knows what filthy habits she’s picked up. I won’t risk her soiling a perfectly good mattress. If she does well on the cot for a few nights, then we can consider moving her to the bed.”

They thought I was in the bathroom, performing whatever unspeakable acts it is that mentally ill people perform in places like that, I suppose. But they were wrong. I was sneaking past their door, on my way to the garage. Jason must have been quite a handyman in his spare time. I found a large selection of hammers on the wall, including an excellent short-handled sledge. I hid it under my bedding. They never even noticed.

The children came in and kissed me good night in a surreal reversal of roles. I lay in the dark on my cot for a long time, thinking of them, especially of Elizabeth, the youngest and weakest, who would naturally be the most likely target of an animal’s attack. I dozed, dreaming sometimes of a smiling Elizabeth-Rose-Delia, sifting snow, wading through drifts; sometimes of the glass cat, its fierce eyes smoldering, crystalline tongue brushing crystalline jaws. The night was well along when the dreams crashed down like broken mirrors into silence.

The house was quiet except for those ticks and thumps all houses make as they cool in the darkness. I got up and slid the hammer out from under the bedding, not even sure what I was going to do with it, knowing only that the time had come to act.

I crept out to the front room, where the cat sat waiting, as I knew it must. Moonlight gleamed in the chaos of its glass fur. I could feel its power, almost see it, a shimmering red aura the length of its malformed spine. The thing was moving, slowly, slowly, smiling now, oh yes, a real smile. I could smell its rotten breath.

For an instant, I was frozen. Then I remembered the hammer, Jason’s lovely short-handled sledge. And I raised it over my head, and brought it down in the first crashing blow.

The sound was wonderful. Better than cymbals, better even than holy trumpets. I was trembling all over, but I went on and on in an agony of satisfaction while glass fell like moonlit rain. There were screams. “Grandma, stop! Stop!” I swung the hammer back in the first part of another arc, heard something like the thunk of a fallen ripe melon, swung it down on the cat again. I couldn’t see anymore. It came to me that there was glass in my eyes and blood in my mouth. But none of that mattered, a small price to pay for the long overdue demise of Chelichev’s Cat in Glass .

So you see how I have come to this, not without many sacrifices along the way. And now the last of all: the sockets where my eyes used to be are infected. They stink. Blood poisoning, I’m sure.

I wouldn’t expect Eleanor to forgive me for ruining her prime investment. But I hoped Jason might bring the children a time or two anyway. No word except for the delivery of a single rose yesterday. The matron said it was white, and held it up for me to sniff and she read me the card that came with it. “Elizabeth was a great one for forgiving. She would have wanted you to have this. Sleep well, Jason.”

Which puzzled me.

“You don’t even know what you’ve done, do you?” said the matron.

“I destroyed a valuable work of art,” said I.

But she made no reply.

COYOTE PEYOTE

Carole Nelson Douglas

Award-winning ex-journalist Carole Nelson Douglas’s fifty-four multi-genre novels often blend mystery and fantasy elements. Douglas also writes the Delilah Street, Paranormal Investigator, urban noir fantasies and was the first author to use a Sherlockian female, diva Irene Adler, as a series protagonist in the New York Times Notable Book of the Year, Good Night, Mr. Holmes . Douglas’s short fiction has appeared in several Year’s Best mystery anthologies. See www.carolenelsondouglas.comfor more information.

Midnight Louie, feline PI, literary lion, and “Sam Spade with hairballs,” has partially narrated twenty-six of her novels, most recently in Cat in a Topaz Tango . Douglas first gave voice to the actual Louie, a koi-snagging stray rescued from an upscale Palo Alto motel, in a newspaper feature.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.