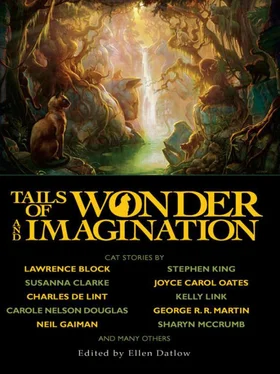

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Rose jerked and kicked and bellowed. In Stephen’s defense, I tell you now it was a terrifying sight, and he was never able to deal well with real fear, especially in himself. He always tried to mask it with anger. We had a neighbor who was a physician. “If you don’t stop it, Rose, I’ll call Doctor Pepperman. Is that what you want?” he said, as if Doctor Pepperman, a jolly septuagenarian, were anything but charming and gentle, as if threats were anything but asinine at such a time.

“For God’s sake, get Pepperman! Can’t you see something’s terribly wrong?” I said.

And for once he listened to me. He grabbed Eleanor by the arm. “Come with me,” he said, and stomped across the yard through the snow without so much as a coat. I believe he only took Eleanor, also without a coat, because he was so unnerved that he didn’t want to face the darkness alone.

Rose was still screaming when Dr. Pepperman arrived fresh from his dinner, specks of gravy clinging to his mustache. He examined Rose’s finger, and looked mildly puzzled when he had finished. “Can’t see much wrong here. I’d say it’s mostly a case of hysteria.” He took a vial and a syringe from his small, brown case and gave Rose an injection, “…to help settle her down,” he said. It seemed to work. In a few minutes, Rose’s screams had diminished to whimpers. Pepperman swabbed her finger with disinfectant and wrapped it loosely in gauze. “There, Rosie. Nothing like a bandage to make it feel better.” He winked at us. “She should be fine in the morning. Take the gauze off as soon as she’ll let you.”

We put Rose to bed and sat with her till she fell asleep. Stephen unwrapped the gauze from her finger so the healing air could get to it. The cut was a bit red, but looked all right. Then we retired as well, reassured by the doctor, still mystified at Rose’s reaction.

I awakened sometime after midnight. The house was muffled in the kind of silence brought by steady, soft snowfall. I thought I had heard a sound. Something odd. A scream? A groan? A snarl? Stephen still slept on the verge of a snore; whatever it was, it hadn’t been loud enough to disturb him.

I crept out of bed and fumbled with my robe. There was a short flight of stairs between our room and the rooms where Rose and Eleanor slept. Eleanor, like her father, often snored at night and I could hear her from the hallway now, probably deep in dreams. Rose’s room was silent.

I went in and switched on the night light. The bulb was very low wattage. I thought at first that the shadows were playing tricks on me. Rose’s hand and arm looked black as a bruised banana. There was a peculiar odor in the air, like the smell of a butcher shop on a summer day. Heart galloping, I turned on the overhead light. Poor Rosie. She was so very still and clammy. And her arm was so very rotten.

They said Rose died from blood poisoning—a rare type most often associated with animal bites. I told them over and over again that it fit, that our child had indeed been bitten, by a cat, a most evil glass cat. Stephen was embarrassed. His own theory was that, far from blaming an apparently inanimate object, we ought to be suing Pepperman for malpractice. The doctors patted me sympathetically at first. Delusions brought on by grief, they said. It would pass. I would heal in time.

I made Stephen take the cat away. He said he would sell it, though in fact he lied to me. And we buried Rose. But I could not sleep. I paced the house each night, afraid to close my eyes because the cat was always there, glaring his satisfied glare, and waiting for new meat. And in the daytime, everything reminded me of Rosie. Fingerprints on the woodwork, the contents of the kitchen drawers, her favorite foods on the shelves of grocery stores. I could not teach. Every child had Rosie’s face and Rosie’s voice. Stephen and Eleanor were first kind, then gruff, then angry.

One morning, I could find no reason to get dressed or to move from my place on the sofa. Stephen shouted at me, told me I was ridiculous, asked me if I had forgotten that I still had a daughter left who needed me. But, you see, I no longer believed that I or anyone else could make any difference in the world. Stephen and Eleanor would get along with or without me. I didn’t matter. There was no God of order and cause. Only chaos, cruelty, and whim.

When it was clear to Stephen that his dear wife Amy had turned from an asset into a liability, he sent me to an institution, far away from everyone, where I could safely be forgotten. In time, I grew to like it there. I had no responsibilities at all. And if there was foulness and bedlam, it was no worse than the outside world.

There came a day, however, when they dressed me in a suit of new clothes and stood me outside the big glass and metal doors to wait; they didn’t say for what. The air smelled good. It was springtime, and there were dandelions sprinkled like drops of fresh yellow paint across the lawn.

A car drove up and a pretty young woman got out and took me by the arm.

“Hello, Mother,” she said as we drove off down the road. It was Eleanor, all grown up. For the first time since Rosie died, I wondered how long I had been away, and knew it must have been a very long while.

We drove a considerable distance, to a large suburban house, white, with a sprawling yard and a garage big enough for two cars. It was a mansion compared to the house in which Stephen and I had raised her. By way of making polite small talk, I asked if she were married, whether she had children. She climbed out of the car looking irritated. “Of course I’m married,” she said. “You’ve met Jason. And you’ve seen pictures of Sarah and Elizabeth often enough.” Of this I had no recollection.

She opened the gate in the picket fence and we started up the neat, stone walkway. The front door opened a few inches and small faces peered out. The door opened wider and two little girls ran onto the porch.

“Hello,” I said. “And who are you?”

The older one, giggling behind her hand, said, “Don’t you know, Grandma? I’m Sarah.”

The younger girl stayed silent, staring at me with frank curiosity.

“That’s Elizabeth. She’s afraid of you,” said Sarah.

I bent and looked into Elizabeth’s eyes. They were brown, and her hair was shining blond, like Rosie’s. “No need to be afraid of me, my dear. I’m just a harmless old woman.”

Elizabeth frowned. “Are you crazy?” she asked.

Sarah giggled behind her hand again, and Eleanor breathed loudly through her nose as if this impertinence were simply overwhelming.

I smiled. I liked Elizabeth. Liked her very much. “They say I am,” I said, “and it may very well be true.”

A tiny smile crossed her face. She stretched on her tiptoes and kissed my cheek, hardly more than the touch of a warm breeze, then turned and ran away. Sarah followed her, and I watched them go, my heart dancing and shivering. I had loved no one in a very long time. I missed it, but dreaded it, too. For I had loved Delia and Rosie, and they were both dead.

The first thing I saw when I entered the house was Chelichev’s Cat in Glass , glaring evilly from a place of obvious honor on a low pedestal near the sofa. My stomach felt suddenly shrunken.

“Where did you get that?” I said.

Eleanor looked irritated again. “From Daddy, of course.”

“Stephen promised me he would sell it!”

“Well, I guess he didn’t, did he?”

Anger heightened my pulse. “Where is he? I want to speak to him immediately.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

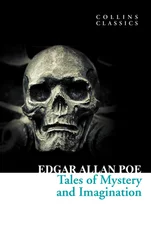

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.