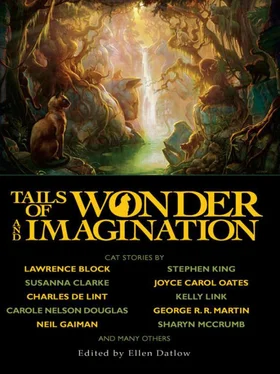

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Exactly. He’d become a student of mesmerism, or hypnotism as he preferred to call it, and suggested we might have a bit of fun probing our dark underminds. We all declined, but Watt was insistent, and at last suborned a hearty local type, old squirearchical family, and—this is important—an inveterate, dirt-under-the-nails farmer. His conversation revolved, chiefly, around turnips.”

“Even his dark undermind’s?”

“Ah. Here we come to it. This gentleman’s wife was present at the gathering as well, and one couldn’t help noticing the hangdog air he maintained around her, the shifty eyes, the nervous start he gave when she spoke to him from behind; and also a certain dreaminess, an abstraction, that would fall on him at odd moments.”

“Worrying about his turnips, perhaps.”

Sir Jeffrey quashed his cigar, rather reproachfully, as though it were my own flippancy. “The point is that this ruddy-faced, absolutely ordinary fellow was cheating on his wife. One read it as though it were written on his shirt front. His wife seemed quite as aware of it as any; her face was drawn tight as her reticule. She blanched when he agreed to go under, and tried to lead him away, but Watt insisted he be a sport, and at last she retired with a headache. I don’t know what the man was thinking of when he agreed; had a bit too much brandy, I expect. At any rate, the lamps were lowered and the usual apparatus got out, the spinning disc and so on. The squire, to Watt’s surprise, went under as though slain. We thought at first he had merely succumbed to the grape, but then Watt began to question him, and he to answer, languidly but clearly, name, age, and so on. I’ve no doubt Watt intended to have the man stand on his head, or turn his waistcoat back-to-front, or that sort of thing, but before any of that could begin, the man began to speak. To address someone. Someone female. Most extraordinary, the way he was transformed.”

Sir Jeffrey, in the proper mood, shows a talent for mimicry, and now he seemed to transform himself into the hypnotized squire. His eyes glazed and half-closed, his mouth went slack (though his moustache remained upright) and one hand was raised as though to ward off an importunate spirit.

“‘No,’ says he. ‘Leave me alone. Close those eyes—those eyes. Why? Why? Dress yourself, oh God…’ And here he seemed quite in torment. Watt should of course have awakened the poor fellow immediately, but he was fascinated, as I confess we all were.

“‘Who is it you speak to?’ Watt asked.

“‘She,’ says the squire. ‘The foreign woman. The clawed woman. The cat.’

“‘What is her name?’

“‘Bastet.’

“‘How did she come here?’

“At this question the squire seemed to pause. Then he gave three answers: ‘Through the earth. By default. On the John Deering.’ This last answer astonished Watt, since, as he told me later, the John Deering was a cargo ship we had often dealt with, which made a regular Alexandria—Liverpool run.

“‘Where do you see her?’ Watt asked.

“‘In the sheaves of wheat.’”

“He meant the pub, I suppose,” I put in.

“I think not,” Sir Jeffrey said darkly. “He went on about the sheaves of wheat. He grew more animated, though it was more difficult to understand his words. He began to make sounds—well, how shall I put it? His breathing became stertorous, his movements…”

“I think I see.”

“Well, you can’t, quite. Because it was one of the more remarkable things I have ever witnessed. The man was making physical love to someone he described as a cat, or a sheaf of wheat.”

“The name he spoke,” I said, “is an Egyptian one. A goddess associated with the cat.”

“Precisely. It was midway through this ritual that Watt at last found himself, and gave an awakening command. The fellow seemed dazed, and was quite drenched with sweat; his hand shook when he took out his pocket-handkerchief to mop his face. He looked at once guilty and pleased, like—like—”

“The cat who ate the canary.”

“You have a talent for simile. He looked around at the company, and asked shyly if he had embarrassed himself. I tell you, old boy, we were hard-pressed to reassure him.”

Unsummoned, Barnett materialized beside us with the air of one about to speak tragic and ineluctable prophecies. It is his usual face. He said only that it had begun to rain. I asked for a whisky and soda. Sir Jeffrey seemed lost in thought during these transactions, and when he spoke again it was to muse: “Odd, isn’t it,” he said, “how naturally one thinks of cats as female, though we know quite well that they are distributed between two sexes. As far as I know, it is the same the world over. Whenever, for instance, a cat in a tale is transformed into a human, it is invariably a woman.”

“The eyes,” I said. “The movements—that certain sinuosity.”

“The air of independence,” Sir Jeffrey said. “False, of course. One’s cat is quite dependent on one, though he seems not to think so.”

“The capacity for ease.”

“And spite.”

“To return to our plague,” I said, “I don’t see how a single madwoman and a hypnotized squire amount to one.”

“Oh, that was by no means the end of it. Throughout that autumn there was, relatively speaking, a flurry of divorce actions and breach-of-promise suits. A suicide left a note: ‘I can’t have her, and I can’t live without her.’ More than one farmer’s wife, after years of dedication and many offspring, packed herself off to aged parents in Chester. And so on.

“Monday morning after the squire’s humiliation I returned to town. As it happened, Monday was market day in the village and I was able to observe at first hand some effects of the plague. I saw husbands and wives sitting at far ends of wagon seats, unable to meet each other’s eyes. Sudden arguments flaring without reason over the vegetables. I saw tears. I saw over and over the same hangdog, evasive, guilty look I described in our squire.”

“Hardly conclusive.”

“There is one further piece of evidence. The Roman Church has never quite eased its grip in that part of the world. It seems that about this time a number of R.C. wives clubbed together and sent a petition to their bishop, saying that the region was in need of an exorcism. Specifically, that their husbands were being tormented by a succubus. Or succubi—whether it was one or many was impossible to tell.”

“I shouldn’t wonder.”

“What specially intrigued me,” Sir Jeffrey went on, removing his eyeglass from between cheek and brow and polishing it absently, “is that in all this inconstancy only the men seemed to be accused; the women seemed solely aggrieved, rather than guilty, parties. Now if we take the squire’s words as evidence, and not merely ‘the stuff that dreams are made on,’ we have the picture of a foreign, apparently Egyptian, woman—or possibly women—embarking at Liverpool and moving unnoticed amid Cheshire, seeking whom she may devour and seducing yeomen in their barns amid the fruits of the harvest. The notion was so striking that I got in touch with a chap at Lloyd’s, and asked him about passenger lists for the John Deering over the last few years.”

“And?”

“There were none. The ship had been in dry dock for two or three years previous. It had made one run, that spring, and then been moth-balled. On that one run there were no passengers. The cargo from Alex consisted of the usual oil, dates, sago, rice, tobacco—and something called ‘antiquities.’ Since the nature of these was unspecified, the matter ended there. The Inconstancy Plague was short-lived; a letter from Watt the next spring made no mention of it, though he’d been avid for details—most of what I know comes from him and his gleanings of the Winsford Trumpet, or whatever it calls itself. I might never have come to any conclusion at all about the matter had it not been for a chance encounter in Cairo a year or so later.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

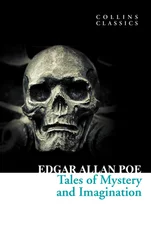

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.