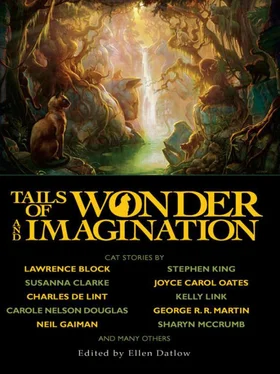

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The boat shifted around dramatically on a shout from the look-out boy. They were heading into shore. Alison doubted whether Lief would even be able to walk.

Jozani is the last vestige of the tropical forest that had at one time covered most of the island. The Red Colobus monkeys make it a tourist attraction, but the monkeys conveniently inhabit a small corner of the forest near the road, not far from one of the spice plantations. Visitors are taken out of the car park, back across the road and down a track to where the monkeys hang out.

The first monkey Craig saw was not remotely red.

“Blue monkey,” the guide said. “Over there,” he pointed through the trees, “is Red Colobus.”

Craig saw a number of reddish-brown monkeys of various sizes playing around in the trees; leaping from one to another, they made quite a racket when they landed among the dry, leathery leaves.

“Great,” Craig said. “What about the leopards?”

The guide gave him a blank look.

“You want see main forest?”

“Yes, I want see main forest.” He followed the guide back to the road and into the car park. The tour around the main forest, Craig knew, would only scratch the surface of Jozani.

“My driver can guide me,” Craig said, slipping a five dollar bill into the guide’s palm. “You stay here. Relax. Put your feet up. Get a beer or something.”

The guide looked doubtful, but Craig beckoned Popo across. He walked slowly, with a loose stride, long baggy cotton trousers and some kind of sandals. “Tell him it’s okay,” Craig said to Popo. “You can take me in.”

After a moment’s hesitation, Popo talked rapidly to the guide, who shrugged and walked back to the reception area defined by a bunch of easy chairs and some printed information and photographs pinned up on boards.

“Let’s go, Popo.”

Popo headed into the forest.

They followed the path until Craig sensed they were starting to double-back on themselves. He stopped, pushed his sunglasses up over his forehead and lit a cigarette.

“I think I want to head off the path a little,” he said as he offered a cigarette to Popo.

The African took a cigarette, and lit it, the $100 bill folded around the pack not lost on him.

“Do you want to take the whole pack?” Craig asked. “I have to head off the path a little way. Leopards, you know?”

“No leopard here.” Popo’s hand hovered in mid-air.

“Witch doctors then. You interested or not?” Craig offered him the bribe again and nodded in the direction he wanted to go. Popo took the pack of Marlboro, slipping the cash out from underneath the cellophane wrapper and folding it into his back pocket. Then he led the way into the forest proper. After a few yards he knelt down at the base of a tree. Craig knelt down beside him and looked where the kid was pointing. There were dozens of tiny black frogs, each no bigger than a finger tip, congregating on some of the broader fallen leaves.

“Here water come,” said Popo. “From sea.”

“Floodwater?”

“Yes. No one come here. Dangerous.”

“Good. Let’s go on, in that case.”

As soon as they hit the sandy bottom, the youth in the bow jumped out and tugged the boat up on to the beach. The kid in the stern pulled up the outboard. Three gangly, raggedy youths walked across the beach to meet them. Alison, Karin, Lief and Anna were forced out of the boat at knifepoint and the two youths exchanged a few words with the newcomers before turning their boat around and pushing off from the shore.

Alison, Karin and Anna had to walk with their hands on their heads to the treeline; Lief’s hands were still tied behind his back. His face betrayed no emotion. Alison was amazed he’d been able to get up and walk. As for Alison, her legs had turned to rubber, despite her small relief at being on dry land. Their new captors were also armed and ruthless-looking.

The wind blew through the tops of the palm trees, an endless sinister rustling. But as they trooped into the forest, the palms thinned out, their place taken by sturdier vegetation. The canopy was so high it created an almost cathedral stillness. All Alison could hear now, apart from their shuffling progress through the trammelled undergrowth, were the occasional hammerings of woodpeckers and the screams of other, unknown birds. From time to time, on the forest floor she would spot sea shells glimmering through the mulch. She jumped when she almost walked into a bat, only to discover it was a broad, brown leaf waiting to drop from its tapering branch. She swiped at it and when it didn’t instantly fall she went ballistic, swinging her arms at it as if it were a punchball. The party halted and two of the African youths came towards her, their knives at the ready. She peered over the edge of sanity at the possibility of panic, stood finely balanced debating her options, caught between self-preservation and loyalty to the group.

Before she knew what she was doing she had taken flight. One of the youths might have taken a swing at her, the point of his knife flashing just beneath her nose. She couldn’t be sure. Something had happened to spur her into action. Action which she instantly regretted, mainly because it was irrevocable and she knew she would never outrun the local boys; also because she had deserted her companions, which according to her own code of honour was unforgivable. Yet she couldn’t be sure they wouldn’t have taken the same chance. Indeed, by running, she had created a diversion which, if they had any sense, they would exploit.

These thoughts flashed through her mind as she crashed through the forest, her flesh catching on twigs and bark and huge serrated leaves yet she felt no pain. Adrenaline surged through her system. She couldn’t hear her pursuers but she knew that meant nothing. These boys would be able to fly. Whatever it took, to render her bid for freedom utterly futile.

As soon as they heard the drumming, Popo became jittery. Craig didn’t give him more than five minutes.

“What is it, Popo?” he asked him. “What’s going on?”

“Mbo,” was all he would say, his eyes darting to and fro. “Mbo.”

It was faint, still obviously some way off, but unmistakably the sound of someone drumming. It wasn’t the surf and it wasn’t coconuts dropping from the palm trees, it was someone’s hand beating out a rhythm on a set of skins. A couple of tom-toms, maybe more, the kind of thing you played with your hand, sat cross-legged—whatever they were called. Craig hadn’t a fucking clue. As for Popo, he was out of there. Craig didn’t even watch him go, back the way they’d come. His hundred bucks had brought him this far, which was all he’d wanted the kid to do.

A mosquito whined by his ear. He brushed it away and walked on, moving slowly but carefully in the direction of the drumming.

He stopped when he heard another sound, coming from over to his right. Another, similar sound, but more ragged, less musical. The sound that would be made, he realised, by someone running. Craig’s mind raced, imagining somone running into danger, and he was about to spring forward to intercept the runner, whom he still couldn’t see, when he saw hovering in the space in front of him a whole cloud of mosquitoes.

They shifted about minutely, relative to each other, like vibrating molecules, seeming at one moment to dart towards him, only to feel a restraining influence and hang back. Because of the noise of the fast approaching runner he couldn’t hear their dreadful whine, but he imagined it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

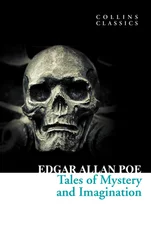

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.