Robert Jordan

Brian Sanderson

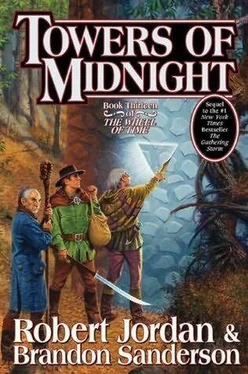

Towers of midnight

It soon became obvious, even within the stedding, that the Pattern was growing frail. The sky darkened. Our dead appeared, standing in rings outside the borders of the stedding, looking in. Most troublingly, trees fell ill, and no song would heal them.

It was in this time of sorrows that I stepped up to the Great Stump. At first, I was forbidden, but my mother, Covril, demanded I have my chance. I do not know what sparked her change of heart, as she herself had argued quite decisively for the opposing side. My hands shook. I would be the last speaker, and most seemed to have already made up their minds to open the Book of Translation. They considered me an afterthought.

And I knew that unless I spoke true, humanity would be left alone to face the Shadow. In that moment, my nervousness fled. I felt only a stillness, a calm sense of purpose. I opened my mouth, and I began to speak.

—from The Dragon Reborn, by Loial, son of Arent son of Halan, of Stedding Shangtai

Mandarb’s hooves beat a familiar rhythm on broken ground as Lan Mandragoran rode toward his death. The dry air made his throat rough and the earth was sprinkled white with crystals of salt that precipitated from below. Distant red rock formations loomed to the north, where sickness stained them. Blight marks, a creeping dark lichen.

He continued riding east, parallel to the Blight. This was still Saldaea, where his wife had deposited him, only narrowly keeping her promise to take him to the Borderlands. It had stretched before him for a long time, this road. He’d turned away from it twenty years ago, agreeing to follow Moiraine, but he’d always known he would return. This was what it meant to bear the name of his fathers, the sword on his hip, and the hadori on his head.

This rocky section of northern Saldaea was known as the Proska Flats. It was a grim place to ride; not a plant grew on it. The wind blew from the north, carrying with it a foul stench. Like that of a deep, sweltering mire bloated with corpses. The sky overhead stormed dark, brooding.

That woman, Lan thought, shaking his head. How quickly Nynaeve had learned to talk, and think, like an Aes Sedai. Riding to his death didn’t pain him, but knowing she feared for him… that did hurt. Very badly.

He hadn’t seen another person in days. The Saldaeans had fortifications to the south, but the land here was scarred with broken ravines that made it difficult for Trollocs to assault; they preferred attacking near Maradon.

That was no reason to relax, however. One should never relax, this close to the Blight. He noted a hilltop; that would be a good place for a scout’s post. He made certain to watch it for any sign of movement. He rode around a depression in the ground, just in case it held waiting ambushers. He kept his hand on his bow. Once he traveled a little farther eastward, he’d cut down into Saldaea and cross Kandor on its good roadways. Then some gravel rolled down a hillside nearby.

Lan carefully slid an arrow from the quiver tied to Mandarb’s saddle. Where had the sound come from? To the right, he decided. Southward. The hillside there; someone was approaching from behind it.

Lan did not stop Mandarb. If the hoofbeats changed, it would give warning. He quietly raised the bow, feeling the sweat of his fingers inside his fawn-hide gloves. He nocked the arrow and pulled carefully, raising it to his cheek, breathing in its scent. Goose feathers, resin.

A figure walked around the southern hillside. The man froze, an old, shaggy-maned packhorse walking around beside him and continuing on ahead. It stopped only when the rope at its neck grew taut.

The man wore a laced tan shirt and dusty breeches. He had a sword at his waist, and his arms were thick and strong, but he didn’t look threatening. In fact, he seemed faintly familiar.

“Lord Mandragoran!” the man said, hastening forward, pulling his horse after. “I’ve found you at last. I assumed you’d be traveling the Kremer Road!”

Lan lowered his bow and stopped Mandarb. “Do I know you?”

“I brought supplies, my Lord!” The man had black hair and tanned skin. Borderlander stock, probably. He continued forward, overeager, yanking on the overloaded packhorse’s rope with a thick-fingered hand. “I figured that you wouldn’t have enough food. Tents—four of them, just in case—some water too. Feed for the horses. And—”

“Who are you?” Lan barked. “And how do you know who I am?”

The man drew up sharply. “I’m Bulen, my Lord. From Kandor?”

From Kandor… Lan remembered a gangly young messenger boy. With surprise, he saw the resemblance. “Bulen? That was twenty years ago, man!”

“I know, Lord Mandragoran. But when word spread in the palace that the Golden Crane was raised, I knew what I had to do. I’ve learned the sword well, my Lord. I’ve come to ride with you and—”

“The word of my travel has spread to Aesdaishar?”

“Yes, my Lord. El’Nynaeve, she came to us, you see. Told us what you’d done. Others are gathering, but I left first. Knew you’d need supplies.”

Burn that woman, Lan thought. And she’d made him swear that he would accept those who wished to ride with him! Well, if she could play games with the truth, then so could he. Lan had said he’d take anyone who wished to ride with him. This man was not mounted. Therefore, Lan could refuse him. A petty distinction, but twenty years with Aes Sedai had taught him a few things about how to watch one’s words.

“Go back to Aesdaishar,” Lan said. “Tell them that my wife was wrong, and I have not raised the Golden Crane.”

“But—”

“I don’t need you, son. Away with you.” Lan’s heels nudged Mandarb into a walk, and he passed the man standing on the road. For a few moments, Lan thought that his order would be obeyed, though the evasion of his oath pricked at his conscience.

“My father was Malkieri,” Bulen said from behind.

Lan continued on.

“He died when I was five,” Bulen called. “He married a Kandori woman. They both fell to bandits. I don’t remember much of them. Only something my father told me: that someday, we would fight for the Golden Crane. All I have of him is this.”

Lan couldn’t help but look back as Mandarb continued to walk away. Bulen held up a thin strap of leather, the hadori, worn on the head of a Malkieri sworn to fight the Shadow.

“I would wear the hadori of my father,” Bulen called, voice growing louder. “But I have nobody to ask if I may. That is the tradition, is it not? Someone has to give me the right to don it. Well, I would fight the Shadow all my days.” He looked down at the hadori, then back up again and yelled, “I would stand against the darkness, al’Lan Mandragoran! Will you tell me I cannot?”

“Go to the Dragon Reborn,” Lan called to him. “Or to your queen’s army. Either of them will take you.”

“And you? You will ride all the way to the Seven Towers without supplies?”

“I’ll forage.”

“Pardon me, my Lord, but have you seen the land these days? The Blight creeps farther and farther south. Nothing grows, even in once-fertile lands. Game is scarce.”

Lan hesitated. He reined Mandarb in.

“All those years ago,” Bulen called, walking forward, his packhorse walking behind him. “I hardly knew who you were, though I know you lost someone dear to you among us. I’ve spent years cursing myself for not serving you better. I swore that I would stand with you someday.” He walked up beside Lan. “I ask you because I have no father. May I wear the hadori and fight at your side, al’Lan Mandragoran? My King?”

Читать дальше