As the German panzers had ground through the outer encirclement belt, frantic calls up the chain of command had led to Vatutin going over into an all-out attack to break into the pocket before the Germans could break out. Such an attack would prevent the encircled Germans from concentrating enough force to break out. He had not reckoned enough on Seydlitz’s single-minded determination not to remain passive about his own fate.

Nevertheless, Vatutin’s attacks were wearing down 6th Army’s exhausted divisions. With its artillery concentrated on supporting the break-out, 6th Army had little with which to oppose 21st and 5th Tank Armies’ attacks. Only the Luftwaffe could fill the gap, but every aircraft was committed to supporting the breakthrough. At that moment when Vatutin’s armies were cracking open the pocket in the north, Kampfgruppe Kempf flung itself south at the 14th Guards.

The soldiers of the 14th Guards were veterans, and their political officers had been hammering home that they were the only thing standing between the German 6th Army and escape. Now was the time to hold firm and extract a bloody vengeance for the sufferings of the Motherland. Their comrades dead about them, half their antitank guns destroyed, and their artillery shattered, they hung on. Rolling towards them were men motivated by a similar determination, but this one was fuelled by desperation. Every weapon the Soviets had left opened up as the panzers flew at them in a wedge formation. To their right came the Hoch- und Deutschmeister, men even more desperate and determined than the panzer crews. They had been through one harrowing retreat and were fed up with being hounded by the Russians. This time Ivan was on the receiving end.

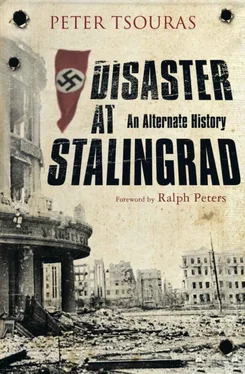

Stalingrad, 8 November 1942

The East Saxons of the 24th Infantry Division were simply not prepared for what they encountered as they entered Stalingrad from the south. They and the other divisions of 11th Army’s LIV Corps thought they knew what the siege and destruction of a fortress city looked like. The men of the 24th Division were, after all, veterans of the epic siege of Sevastopol. Had they not finally broken the formidable Fort Stalin?

Sevastopol had fallen in the bright July sunshine of the Crimea framed by the blue water of the Black Sea. Stalingrad was not like that at all. Winter had left the blackened ruins sprinkled with filthy snow under dull, leaden skies. The destruction was far more thorough, and everywhere among the broken brick and concrete were the bodies, frozen excrement, and the detritus of countless used-up divisions. The few people they saw were civilians scavenging through the ruins. They fled as soon as they saw Germans. The East Saxon regiments filed up in awe past the grain elevator, all scorched and with huge, jagged holes.

Eventually, they met a patrol in SS uniform whose men spoke with a thick Danish accent and claimed to be from SS Wiking. They guided them to an outpost of that division. The commander of the lead regiment was put in touch with the senior SS officer, who excitedly told him that air reconnaissance just reported large numbers of Soviet troops marching back up the west end of the pocket towards the city. On his own authority the commander changed the direction of march to the northwest. His decision was immediately confirmed by his division, corps and army commanders. The rest of the corps was turned in that direction as well.

They were in a race to intercept the enemy’s 64th and 299th Rifle Divisions of 66th Army, directed by Stalin himself to retake the city from the German contingent that had occupied it. Stalin would have been far less satisfied with this action had he known that the army commander had selected the 64th Rifle Division for the mission. Given Stalin’s obsession with treason, the knowledge that this division was being trusted to retake the city that bore his name would have enraged him. As well it should: the men of the 64th were still disaffected from their suppressed mutiny in August and now bore a deep and abiding hatred for the ‘justice’ meted out to so many comrades.

Werewolf, 8 November 1942

Hitler’s face turned red. His eyes glowed with rage. His staff knew the signs of an impending tirade. In his hand was the message from Manstein that finally had answered his constant stream of precise orders, every one of which had been disobeyed.

Mein Führer,

There are… cases where a senior commander cannot reconcile it with his responsibilities to carry out an order he has been given. Then, like Seydlitz at the Battle of Zorndorf, he has to say: ‘After the battle the King may dispose of my head as he will, but during the battle he will kindly allow me to make use of it.’ No general can vindicate his loss of a battle by claiming that he was compelled — against his better judgement — to execute an order that led to defeat. In this case the only course open to him is that of disobedience, for which he is answerable with his head. Success will usually decide whether he was right or not. 17

I have disobeyed your specific orders in order to fulfill the greater strategic goal of destroying the Red Army which you yourself have stated repeatedly. We have reached the crisis. Now let me finish this battle, and I will lay before you a great victory.

Manstein

Stauffenberg was ready. An aide hustled in a young soldier dressed in the black uniform of the Panzertruppen, his arm in a sling. At his throat hung a Knight’s Cross. ‘Mein Führer, allow me to introduce a front soldier straight from the Kalach pocket, Hauptmann Bruno Detweiler. He has a message for you from the men of the 6th Army.’

If there was anything that tempered Hitler’s conduct it was a front soldier — he imagined he had a bond with the combat veterans dating to his own service in the trenches of the First War. Here was one who had been wounded in battle and wore the Knight’s Cross, proof of his valour. The fires in Hitler’s eyes banked, and he suddenly looked kindly.

The young man was plainly awestruck. He pulled himself together, saluted, and began his report. He described the conditions of the fighting, the state of the men and their morale. Then he said,

Mein Führer, the men have great faith in you. You have promised them that you will rescue them from the encirclement, and the men say repeatedly that their Führer has never broken his word to them.

Hitler was greatly affected by the speech. He took the Hauptmann’s hand in both of his and warmly shook it. When the man had departed, he grumbled to Stauffenberg, ‘I will give Manstein enough rope to hang himself.’ 18

Kotelnikovo, Army Group B Headquarters, 9 November 1942

Manstein had no intention of measuring himself for a noose. He was preparing one for Zhukov. He had also had one in mind for the GröFaZ himself with the help of the other Gerichten. But the battle was reaching that point when all the previous actions, both German and Russian, suddenly presented opportunities. Most of those opportunities were now tumbling into the hands of the Germans.

The 11th Army was wheeling in on the Soviet flank and rear as well as breaking into the Kalach Pocket. It was for this reason that he had fought Hitler tooth and nail to retain it as a powerful operational reserve. Now his Sevastopol veterans were flooding through the ruins of Stalingrad. The reports kept streaming in:

09.30, 11th Army HQ. Two enemy divisions defeated on the outskirts of the city. The lead rifle division collapsed at first contact. Thousands of men have just shot their political officers and surrendered.

09.52, LX Panzer Corps HQ. Panzer Corps destroyed two remaining tank brigades; linked up with Panzergruppe Kempf. Resupply convoys are flowing into the pocket.

Читать дальше