A hard-topped truck and a Rapier armoured car were already parked on the waste ground, the latter standing with its view slits shuttered but its engine idling. Owain spun the Land Rover around and reversed into a space.

A blue haze of cigarette smoke was issuing from one of the vents in the armoured car. The guard had gone across to a female superior standing beside a long cargo lorry that was parked right across the entrance to Regent Street. Owain saw the woman look towards him before taking his ID and climbing into the back of the lorry. Cables were trailing from its rear into an open manhole on the pavement.

Owain waited, stamping his feet on the powdery snow, stretching his shoulder and neck muscles. A big RAF helicopter went by, the red-and-blue decal on its midsection enclosed by a circle of yellow stars. None of the personnel on the ground looked up as it went past.

The cles. opter was an Euro Avionics HT-11, I gleaned from Owain, popularly known as the Fishtail for its forked rear end. It was used as a vehicle and troop carrier, and Owain had flown in one many times, especially while on the eastern front. I had a brief image of him driving down a ramp from the belly of such a craft into a cold predawn darkness.

The woman emerged from the trailer. Her head was swaddled in a grey fur hat, the earflaps hanging loose in the wind.

“Good evening, major,” she said. “A raw day to be out and about.”

“Indeed,” Owain replied.

“Perhaps you’d like to sit in your vehicle.”

Was this a suggestion or an order? She had a unit leader’s patches, was roughly the same rank as him. But with jurisdiction. Owain decided not to make an issue of it. He climbed back into the Land Rover and wound down the window. He’d left its engine running.

“I’m here half the night myself,” she went on, turning his ID in her mittened hands. Owain was sure she had already checked it with the database. “The graveyard shift. Much rather be curled up in front of the TV with a mug of something hot.”

Owain was trying to place her accent. South African or Rhodesian, he decided; he didn’t bother to ask.

She was still holding on to his card. Owain drummed his gloved fingers on the steering wheel. He was beginning to regret having made his intentions explicit.

She reached in and extracted his wallet from the dashboard pouch. Removing a mitten, she replaced the card in the wallet.

“Well then,” she said, handing it back through the window, “everything appears to be in order. But it’s not going to be possible to visit the site.”

Owain was striving hard to control his impatience. “I just wanted to see what damage it caused. My driver and I were nearly killed. Check it for yourself if you don’t believe me.” He was certain she had already done so. “I’m only just out of convalescence.”

“You have my sympathies. But I’m afraid no one’s being allowed in without authorisation.”

“Look,” Owen said, “I’m Sir Gruffydd Maredudd’s adjutant. Do I really have to go back to the WO and get his signature?”

“That would be entirely appropriate. You would also need to make sure you’re suitably dressed. There’s a concern that the explosion might have stirred up toxins. My orders are to keep everyone out unless they have security clearance. You will appreciate that they have to be applied without exception.”

This was at odds with what his uncle had t

Owain inhaled sharply. I could feel his fury mounting, and his struggle to control it. It was an emotion unfamiliar to me, or at least long forgotten.

He rammed the gear lever into first. The woman stepped back.

“Lights on, major,” she reminded him. “I wouldn’t want to hear that you’d had an accident.”

Owain drove away, heading straight down Piccadilly. The night fog was already rolling up from the river. This decided him. Out of sight of the roadblock he turned sharply right into an unmanned intersection, driving parallel with Regent Street into Saville Row.

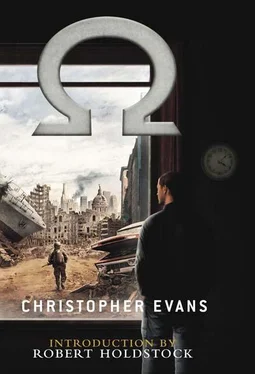

The district was lined with mouldering tenement blocks. The central area of London had suffered from repeated aerial attack over the last half-century and much of it was now depopulated. The buildings, raised hastily on bomb sites in the nineteen sixties, had long been abandoned, the factory workers dispersed to rural sites.

He turned into a side street, into a dead end. Big coils of razor wire had been piled against a breezeblock wall about ten metres high. Above the old yellow-and-black biohazard signs were new ones showing anti-personnel mine symbols. A stark warning in English, French and German said: ENTRY FORBIDDEN: INTRUDERS WILL BE SHOT

I could feel Owain’s powerful urge to investigate, regardless of any dangers. He switched off the Land Rover’s lights but left the engine running. I wanted him to stop, but my anxiety counted for nothing, wasn’t even registered. What would happen to me if he were killed?

The tenement blocks were all sealed off, their doors and windows long bricked up. Owain skirted the barrier cautiously. The razor wire had been laid in haste, thrown down almost casually against the base of the wall, the new signs hammered in with masonry nails. Flattening himself against the wall, he managed to slip past the wire without getting snagged.

The wall itself was at least twenty years old. There were gaps in the pointing, and hardened cement had oozed out like cream from a sponge cake. In one corner, ice from an overflow pipe had piled up, reducing the height by half.

Purposefully Owain began to root around in the snow. Amongst the broken bricks and the rotting cement bags was a pallet of unused blocks, abandoned and forgotten. He withdrew an army knife from his belt and cut off lengths of plastic packing strips before knotting them together into a crude lasso.

The overflow pipe projected from beneath the guttering on the corner of the tenement wall. He managed to hook the noose over it at his second attempt. He tugged several times; it held. Confident that his gloves would prevent the strips from cutting into his hands, he began hauling himself up.

All this was conducted with total concentration on the task. He had a more practical bent than me and was also much fitter. Despite not being fully recovered from the bomb blast, he scaled the wall effortlessly and perched on its lip.

He was just high enough to peer across the deserted street and over the broken frontages into the Soho wasteland. The fog was rapidly thickening, making visibility intermittent. But parts of the area were lit with fuzzy halos of arc-lamp light, and he was able to see the outlines of bulldozers and other earth-shifting equipment. They were moving about amid a tangled, lumpy landscape.

The drone of their engines carried to him. He glimpsed a lorry piled high with debris, driving away into the fog. A few figures were discernible too—men who looked as if they were wearing hardhats and coveralls rather than decontamination suits. Some were directing dump trucks; others were hitching rides on open-topped ATVs. The noise of a mini avalanche reached him as another unseen lorry received its load. Squinting harder he saw that the mounds comprised mountains of earth in which were embedded the broken outlines of heavy machinery parts.

The area was supposed to have been cleared years ago, but it looked as if it had suffered saturation bombing, everything churned up and mangled beyond recognition. He cursed the fact that he didn’t have binoculars and could only rely on murky impressions. But what was certain was that this was no decontamination team: on the contrary, as much of the ground was being turned over as possible.

A wave of giddiness swept over him. We almost went plummeting down. Another sound reached us: that of an approaching helicopter.

Читать дальше